Written by Moya Crockett

Moya is Contributing Women’s Editor at stylist.co.uk and Deputy Editor of Stylist Loves, Stylist’s daily email newsletter.

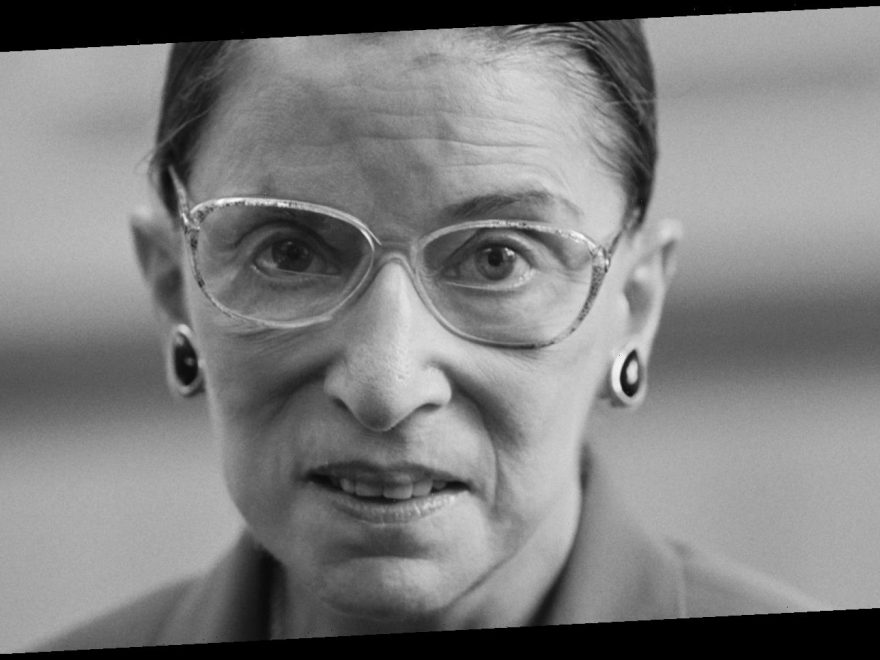

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the second female Supreme Court Justice in the US and a lifelong champion of gender equality, has died from metastatic pancreatic cancer aged 87. Her loss will be felt around the world.

There is a moment in the award-winning 2018 documentary RBG that drives home how much of a trailblazer Ruth Bader Ginsburg really was. The screen is filled with a photo of dozens of people standing on the college steps at Harvard Law School in the late 1950s.

At first glance, you’d be forgiven for thinking there are no women in the picture at all: just rows and rows of pale, bespectacled young men. And then the camera zooms in to focus on the face of a young woman, standing right at the edge of the class. Next to the men in suits, she looks almost laughably tiny and distinctly feminine, with immaculately coiffed hair and a dark slash of lipstick. But her expression, above a girlish Peter Pan collar, is deadly serious. Her gaze cuts through you like a knife

Unapologetically female, often outnumbered, and not here to mess around: if you were looking for a photo to sum up Ginsburg, you could do worse than this one. When that picture was taken, hundreds of state and federal laws barred women in the US from existing on equal footing with men.

Yet over the course of a law career beginning in the early 1960s, Ginsburg helped advance gender equality in the US by leaps and bounds, building a reputation as one of the world’s brightest legal minds and fiercest champions of women.

Born Joan Ruth Bader to a working-class Jewish family in Brooklyn in 1933, Ginsberg faced plenty of sexism in her early life. After her beloved mother died the day before her high school graduation, she was refused the right to attend the minyan, a traditional Jewish prayer service, because she was a woman.

Despite having gone to Cornell University on a full scholarship, she was only able to get a job as a typist after graduation – and was demoted with a pay cut upon becoming pregnant with her first child, aged 21.

In 1956, Ginsburg and her husband Marty (who she described as “the first boy I ever knew who cared that I had a brain”) began attending Harvard Law School.

She was one of only nine female students in a class of around 500, prompting the dean to ask her why she’d taken a place that “should go to a man” (a moment immortalised in the 2018 film On The Basis Of Sex, starring Felicity Jones). After graduating, one of her professors recommended her for a job with a Supreme Court justice, but she was rejected on the basis that the judge wasn’t ready to hire a woman, especially a mother. The list of indignities went on and on.

But Ginsburg never gave up. She became a legal clerk, then a researcher at Columbia Law School, then a professor at Rutgers Law School in New York (at the time, there were fewer than 20 female law professors in the US). In 1971, she wrote her first Supreme Court brief in the case of Reed v. Reed, representing a woman who believed her ex-husband should not be automatically appointed the executor of their late son’s estate over her.

Ultimately, the all-male Supreme Court sided with Ginsburg – the first time the court had ruled that discrimination based on gender was unconstitutional. Ginsburg, who credited the Black lesbian feminist lawyer Pauli Murray with inspiring the legal argument in her brief, described the case as a “turning point”.

In 1972, Ginsburg co-founded the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), with the goal of gradually and deliberately chipping away at sexist laws. Within two years, the project had participated in over 300 gender discrimination cases, and by 1976, Ginsburg had won six landmark gender discrimination cases before the Supreme Court.

She was also fond of arguing cases in which men were negatively affected by sex-based legislation. In 1973, she successfully fought for the right of fathers to receive state benefits if their wives passed away, something that had previously only been available to widowed mothers. By taking on these cases, Ginsburg opened many people’s eyes to the universal benefits of feminism. “His case was the perfect example of how gender-based discrimination hurts everyone,” she said

In 1993, Bill Clinton appointed Ginsburg to the Supreme Court, making her the second woman (after Sandra Day O’Connor) to rise to that rank. During her confirmation hearing, she emphasised that she would continue to work for gender equality and took the unprecedented step of explicitly endorsing abortion rights.

“It is essential to woman’s equality with man that she be the decision maker,” she told senators, in her calm, clear voice. “If you impose restraints that impede her choice, you are disadvantaging her because of her sex.” She was confirmed by a vote of 96 to three. In contrast, when Trump appointed Brett Kavanaugh – who has been credibly accused of sexual assault by Dr Christine Blasey Ford – to the Supreme Court in 2017, his confirmation was secured by a margin of just two votes.

The makeup of judges on the Supreme Court has become more conservative since Ginsburg was first appointed; Trump has appointed two judges in just four years. She often spoke of the importance of finding common ground with people of different ideological stripes, but in her final years on the court, she was often a dissenting liberal voice arguing for the rights of women and ethnic minorities. As recently as March this year, she was challenging attempts to roll back abortion access in Louisiana.

Ginsburg was first diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2009, and experienced several bouts of ill health in recent years. In July, she announced that she was undergoing chemotherapy for a recurrence of cancer, but refused to stop working, saying: “I have often said I would remain a member of the [Supreme] Court as long as I can do the job full steam. I remain fully able to do that.

The loss of Ginsburg as a symbol of female empowerment and resilience will be keenly felt by feminists around the world. But for pro-choice progressives in the US, her death is nothing short of terrifying. The Republicans will likely attempt to fill her empty seat with a new conservative judge before the US presidential election in November, something that will affect legislation in the US for decades to come.

If they are successful, there is a real and credible danger that Roe v. Wade – the landmark 1973 legislation that legalised abortion across the US – could be overturned. Ginsburg was well aware that her death could affect US law for generations. Shortly before she died, she told her granddaughter that her “most fervent wish” was that she not be replaced “until a new president is installed”.

It is acutely painful that one woman’s death could lead to the erosion of rights that she fought to establish and preserve for her entire adult life. But if Ginsburg’s long, dogged, difficult fight for gender equality shows us anything, it’s that admitting defeat is not an option. “Fight for the things that you care about,” she told a group of female students in 2015. She did – and we must.

Images: Getty

Source: Read Full Article