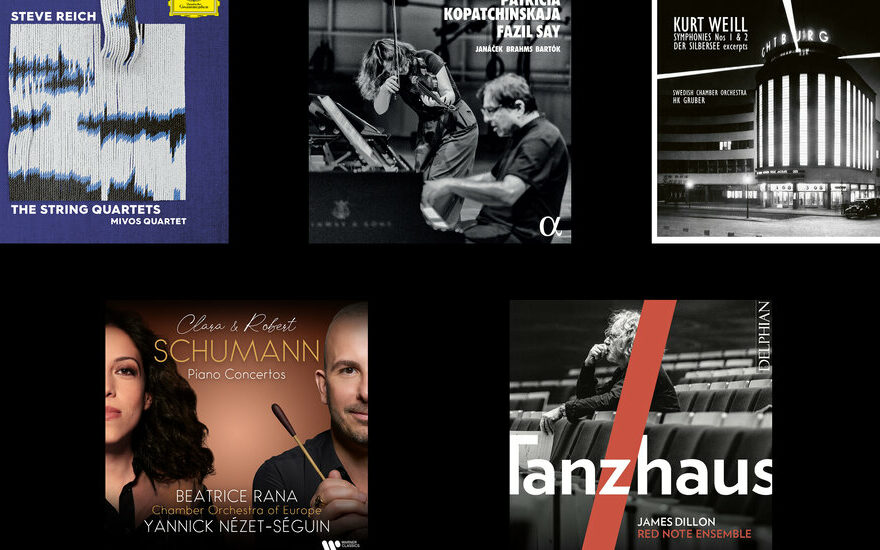

‘Clara & Robert Schumann: Piano Concertos’

Beatrice Rana, piano; Chamber Orchestra of Europe; Yannick Nézet-Séguin, conductor (Warner)

It was more than just a custom, almost an unwritten law, for decades of recording history: If a major pianist was to record Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto, and with a major conductor at their side, then they were to pair it with its counterpart by Edvard Grieg, also in A minor.

But here are Beatrice Rana and Yannick Nézet-Séguin to suggest that it makes more sense to pair the Schumann with another concerto in the same key, an earlier one by the performer who premiered it: Clara Wieck, or Schumann, as she became once she married Robert. If her influence on him has long been intellectually clear, it is good to have it be made so audibly as it is here, too.

Clara’s concerto does stand on its own: One of the striking things about Rana’s recording is how much dreamier her approach is than that taken in Isata Kanneh-Mason’s recent account, yet how well the piece tolerates both. Rana’s is a reading full of elegance, and ever so subtle in its inflections, but there is a strength of purpose to it, too. It’s a joy to hear.

The other Schumann is far less so, though Rana’s playing remains admirable. The problem here is Nézet-Séguin, and the incorrigible fussiness in his conducting. Why Nézet-Séguin persists in making records with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe rather than any of his North American ensembles is a mystery, though it’s a fine band; Claudio Abbado once used it to bring clarity to music like this, but the orchestra’s virtuosic immediacy doesn’t help Nézet-Séguin restrain himself. DAVID ALLEN

‘Janacek — Brahms — Bartok’

Patricia Kopatchinskaja, violin; Fazıl Say, piano (Alpha Classics)

There is no piece of music — works by Tchaikovsky or Schoenberg, or an old folk tune — that the violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja cannot play in a way that unwinds your expectations and forces you to hear it anew. So it is with the latest chapter in her partnership with the intrepid Turkish pianist and composer Fazil Say. The Janacek sonata that opens this recording and the Bartok Sonata No. 1 that closes it clearly play to the duo’s strengths: curiosity, an impatience with convention and exceptional technique. They pounce, almost too eagerly, on each of the Janacek’s lightning-quick mood changes; and in the Bartok, a piece in which the two instruments work virtually at cross purposes, they achieve an ESP-like mutual responsiveness.

Their rendition of Brahms’s Violin Sonata No. 3 in D minor, however, is the paramount achievement here. Resisting the urge to swath this wistful music in a big luxuriant tone, Kopatchinskaja adopts a timbre that’s sometimes bristly, sometimes gossamer-light. She and Say push the music to extremes: The quiet moments seethe and the outbursts approach violence, but it’s all done with impeccable control. The piece sounds bereft and heartbroken even as it avoids the clichés of Romanticism. It’s not the way I’d want to hear it played every time, but it’s invaluable for offering a glimpse deep into a work you might have thought predictable, which is exactly what these imaginative musicians are after. DAVID WEININGER

James Dillon: ‘Tanz/haus: triptych’

Red Note Ensemble; Geoffrey Paterson, conductor (Delphian)

James Dillon doesn’t appear to love the limelight. In the 1990s, this composer distanced himself from the New Complexity label almost as soon as it came into circulation in European contemporary music circles. And this release is only the seventh album devoted exclusively to Dillon’s works since his debut on the NMC label back in 1992. But he has a way of making each appearance count. On the Red Note Ensemble’s album, you can hear traces of his earlier, chaos-courting soundscapes (like “Helle Nacht”). Yet this new chamber music triptych dances more than it thunders.

The first movement alone shows Dillon’s penchant for drama and finely judged blends. Brief songs for clarinet snake between string trills and percussive fillips. He toys with sparseness, then a new pitched percussion chord leads to a subtle electric guitar declaration; it’s lightly distorted, yet not driven in an overly obvious way. The most aggressive material — toward the end of the movement — is given to acoustic instruments. Then, at the close, sustained wisps of accordion bring to mind the deep listening music of Pauline Oliveros. European complexity? American Minimalism? The categories aren’t all that helpful: It’s James Dillon. Thankfully, these same players will release another album of his recent work in March. SETH COLTER WALLS

‘Weill: Orchestral Works’

Swedish Chamber Orchestra; HK Gruber, conductor (Bis)

I’ve seen enough interminable performances of “The Threepenny Opera” to know that Kurt Weill’s music lives or dies on its delivery. Like a Mozart of the 20th century, he wrote works that are deceptively straightforward, almost cruelly transparent, that in their interpretations must be precise yet not stolid, and able to convey multiple — sometimes contradictory — meanings within a single, irresistibly singing phrase.

With that said, a mea culpa: A couple of years ago, in a survey of Weill’s European period — roughly the first half of his career, before he fled Nazi Germany and eventually made his way to the United States — I wrote that his second symphony, “Fantaisie symphonique” (1934), in its similarity to the composer’s stage works, was “likable, but to what end?” The Swedish Chamber Orchestra’s new album of Weill’s two symphonies, as well as excerpts from his 1933 music-theater masterpiece “Der Silbersee,” has arrived with an answer.

The collection is conducted by HK Gruber, a standard-setting interpreter of Weill’s music, who has been inspired by the composer in his own works. His account of the first symphony (1921) tightly controls what could easily seem scattered; and he sings in the “Silbersee” excerpts, with the gravely, unrefined affect of Lotte Lenya that will be instantly familiar to those who know his 1977 song cycle “Frankenstein!!” The second symphony unfurls with an ease that becomes more disturbing as, from behind the wit and tunefulness, emerge flashes of heartbroken nostalgia and martial terror. The scores comes out sounding more personal, if documentary, for it — a postcard from a precarious Europe on the brink. JOSHUA BARONE

‘Steve Reich: The String Quartets’

Mivos Quartet (Deutsche Grammophon)

Steve Reich’s three string quartets — “Different Trains” (1988), Triple Quartet (1998) and “WTC 9/11” (2010) — have been recorded in standard-bearing versions by Kronos Quartet, the group for whom Reich wrote them.

So why mess with the canon?

For one reason: Reich himself suggested that the Mivos Quartet juxtapose all three works on one album for the first time. Another apparent impetus: The astute Mivos players bring their own inflections to this music. The violinists Olivia De Prato and Maya Bennardo, the violist Victor Lowrie Tafoya and the cellist Tyler J. Borden infuse the first movement of “Different Trains,” an evocation of Reich’s cross-country train travels as a young Jewish boy in the late 1930s and early 1940s, with a crackling zippiness that suggests a blithely sunny America blind to concurrent terrors in Europe. In Triple Quartet, the players’ emphasis on rhythm and attack underscores the Bartok-like shifts and sheer ferocity of the outer movements.

More than two decades after the terror attacks of Sept. 11, “WTC 9/11” — which, like “Different Trains,” incorporates the “speech melody” of taped audio footage and witness accounts — is still viscerally raw, and an emotionally difficult listen. The Mivos reading is smoother than the gut urgency of the Kronos Quartet, but this current recording is nevertheless an affirmation: These are essential works for generations of musicians and listeners. ANASTASIA TSIOULCAS

Source: Read Full Article