“Yo, Herman,” Twyla Tharp calls out across a large, crowded studio. Rehearsal is about to begin, and dancers are milling around, chatting and stretching. But not Herman Cornejo. He’s in a corner, sketching out small movements as he runs through a sequence of steps in his mind. Seeing him lost in thought, Ms. Tharp walks over, placing a hand on his shoulder. The two confer quietly, like confidants.

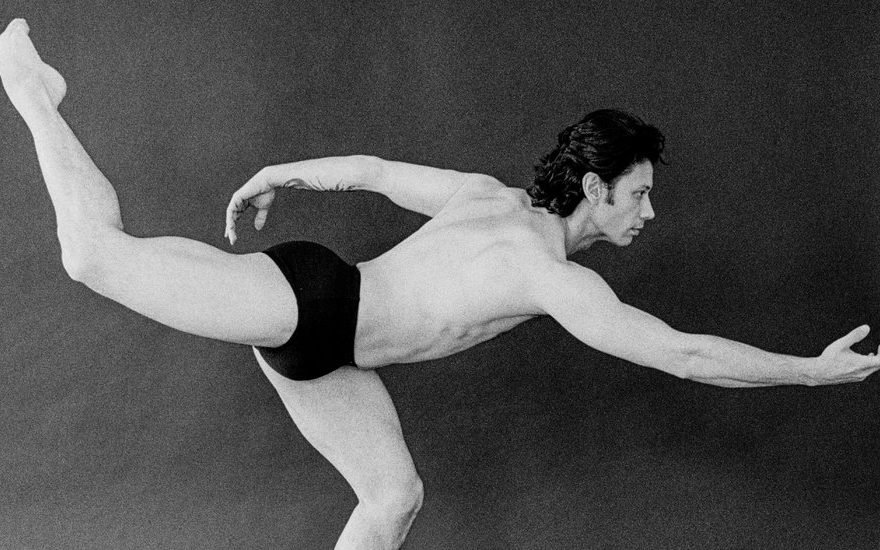

Mr. Cornejo has a way of being in a group but not quite part of it, an island of intensity amid the tumult. And that quality of quiet absorption translates onto the stage too; he can elevate an entire ballet with his focus and polished bravura. And yet he never gives the impression of wanting to steal the show. Precision, control and a soaring, exhilarating jump that leaves your heart in your throat — they all become something greater: the suggestion of a state of mind. Without the usual fanfare that attends stars, he has become one of the most admired male dancers of his generation.

“When I was 20,” he said, “it was all about the dancing, but now it’s about interpreting something onstage. The technique is there.”

This is Mr. Cornejo’s 20th season with American Ballet Theater, and in honor of the occasion, Ms. Tharp, one of America’s greatest choreographers, has made a new ballet, “A Gathering of Ghosts,” set to Brahms’s lush second string quintet. In addition to premiering at the opening gala, it will be part of a special 20th-anniversary program, on Oct. 26.

The ballet revolves around him, almost as if he were conjuring the other characters. In one sequence, he illustrates the brilliance with which he shapes and colors movement: He stretches and retracts, allowing a ripple to undulate through his body, then initiates a series of turns, going faster, then slower, then faster again. He seems to respond to messages locked in the music, creating a character even when there is no actual story.

“I see him as a hero,” Ms. Tharp said during a rehearsal break, “something that’s out of vogue these days. And heroes are always, to a certain extent, alone.”

Ms. Tharp knows him well, having spotted him early on and given him a central role in her 2000 ballet “The Brahms-Haydn Variations” when he was still in the corps. “She was the first choreographer to choose me for a principal role simply because she thought I deserved it,” he said.

Though his talent was recognized at a very young age and his rise through the ranks was quick — he was promoted to soloist at 19, after just one year in the company, and to the top rank three years later — it took several more years for him to be assigned the roles he craved and felt he deserved. Those were the dashing romantic leads — princes, warriors, lotharios — who hold together the stories of the great classical ballets. At 5-foot-6, Mr. Cornejo is several inches shorter than the long-limbed standard for male dancers cast in these parts, and it took Kevin McKenzie, the artistic director of Ballet Theater, a while to see him in this light.

“He proved us all wrong,” Mr. McKenzie said, “just through his sheer sensibility in classical works and the dynamics of his dancing.” Once Mr. Cornejo had proved himself, the roles kept coming: Basilio in “Don Quixote” in 2005, Romeo in 2007, Siegfried in “Swan Lake” in 2013. At 38, he is still making role debuts: the love-struck Des Grieux in “Manon” this past spring, and now George Balanchine’s “Apollo,” which he will dance in New York for the first time at the evening planned in his honor.

Mr. Cornejo, who was born in the province of San Luis in central Argentina and grew up in Buenos Aires, started studying ballet at 8, following his older sister, Erica — they are two years apart — despite being painfully shy.

“He would watch class through the window,” she said in a telephone interview from Boston where she recently retired from Boston Ballet, “and one day, my teacher at the time, Wasil Tupin, asked him into his office and offered him some candy. We don’t know what he said, but the next day Herman was in class, and he already knew how to turn and jump, just from watching.”

He picked up steps like a sponge. Another teacher from those early years, Katty Gallo, remembered him as “un chico geniecito,” a little genius, who could seemingly do anything asked of him.

In addition to private training, Herman and Erica both attended the Instituto Superior de Arte, the official ballet school of the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, where they were in the same cohort as Marianela Nuñez and Luciana París. Their mother, Elsa, spent hours shepherding them from ballet classes to school and back. Their father, Ricardo, a career officer in the Argentine Air Force, took night shifts as a security guard to help pay for their training.

At 14, again following his sister, Mr. Cornejo joined Julio Bocca’s touring group Ballet Argentino. Still practically kids, the Cornejos became professional dancers, touring for much of the year. Mr. Bocca remembers how impressed he was with the siblings, and especially Herman: “He was like a purebred foal,” Mr. Bocca said in a phone call from Uruguay, where he lives, “with all that energy but a refinement in his technique and in his approach extraordinary in someone so young.”

On Mr. Bocca’s recommendation, Herman Cornejo entered the International Ballet Competition in Moscow despite being only 16, below the official age of entry. He won the gold medal, the youngest dancer ever to do so. It was around that time that the Cornejos started making plans to audition for American Ballet Theater, where Mr. Bocca was a principal dancer. In 1998, after performing a balleticized tango for a private function at the Metropolitan Opera House, they got their wish. (The Cornejos will reprise that tango in the Oct. 26 performance.) Mr. McKenzie offered them both spots in the studio company. Mr. Cornejo was 17.

Since then, he has danced most of the classical repertory, as well as 20th-century works by Michel Fokine, Frederick Ashton — most memorably, Puck in “The Dream” — Balanchine, Merce Cunningham, Mark Morris, and others. Ballet Theater’s resident choreographer Alexei Ratmansky made striking parts for him in “Serenade After Plato’s Symposium” and “Seven Sonatas.”

Mr. Cornejo is remarkably adaptable and quick to pick up steps. “Herman always knows my choreography as well as his,” Misty Copeland, a frequent partner, said in a telephone conversation.

He says his versatility is related to his curiosity about movement: “I like to understand the challenges that lie within the styles of different choreographers,” he explained, “and to forget what my classical body wants to do.” His clean, unmannered technique — in part the product of his Argentine training, which combines various schools of ballet — helps too.

A turning point came in 2013, when he took a leave from the company to perform in an intimate dance-theater work, “Chéri,” based on Colette’s novel about an aging courtesan and her younger lover, by the choreographer Martha Clark. His partner was the much-loved ballerina Alessandra Ferri, then semiretired. (She has since regularly returned to the stage.) The two developed an intense stage chemistry; three years later Ms. Ferri asked him to partner her in “Romeo and Juliet” at Ballet Theater, a role she hadn’t danced in seven years.

Working with Ms. Ferri propelled Mr. Cornejo to a level of stardom he hadn’t known before. He developed a more mature, simmering stage persona. Whereas before he had danced mostly alongside Xiomara Reyes, who retired in 2015, he now partnered a variety of ballerinas, including Maria Kochetkova and Ms. Copeland, who will dance the role of Terpsichore opposite his Apollo.

“To become a really good partner you need to dance with different people,” he said, “experience all kinds of bodies, legs, emotions. You have to build that chemistry.”

Though he remains at his peak as a dancer, the wear and tear of a career begun at 14 has started to take its toll. Dancing still feels good, he says, but the recovery the next day has gotten harder. In the last few years he has had a series of calf injuries that have kept him offstage for months at a time.

He takes better care of himself now, with a rigorous regimen of physical therapy, cross-training and nutrition. He recently got married, to an Argentine journalist, with whom he bought a townhouse in the Bronx. They are expecting their first child in January.

His ability to dazzle is undimmed. At a performance of “The Sleeping Beauty” last spring, in the role of the prince, he executed a highly technical solo requiring extreme precision but lacking the usual crowd-pleasing tricks. For much of it, he seemed to hover above the stage, barely touching the floor, while sustaining the ebb and flow of the music. He was, in every sense, the prince.

The applause started about halfway through in a slow crescendo and lingered for a long time afterward. “I felt that moment, and I don’t think I can do it better,” he said. “I don’t think about the future or how much time I have left. Just about that moment, that performance.”

Source: Read Full Article