FICTION

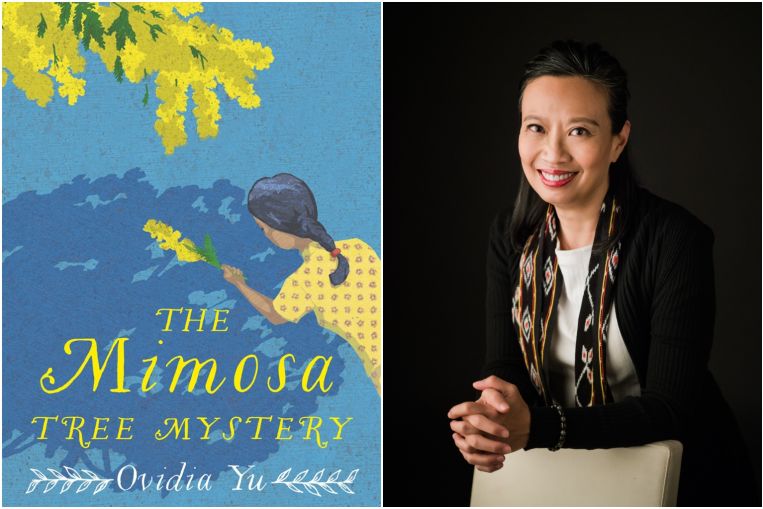

THE MIMOSA TREE MYSTERY

By Ovidia Yu

Constable/ Paperback/311 pages/ $18.95/ Available at bit.ly/MimosaTreeMys_Yu

3.5 stars

Fans of home-grown writer Ovidia Yu’s crime mystery series featuring young Peranakan sleuth Chen Su Lin will be thrilled to know that the series has legs beyond its three instalments set in 1930s Singapore. But they should brace themselves for darker fare, as Yu takes on the Japanese Occupation.

The Mimosa Tree Mystery opens with a rude shock: Su Lin and her family are ordered out of their house before dawn by Japanese soldiers and told to report to the school field. Her uncle is singled out by an informer and dragged off.

Su Lin is then approached by the cryptic Hideki Tagawa, a powerful figure in the Kempeitai, or Japanese secret police. He offers her a deal: to free her uncle, she must solve the murder of her neighbour, wealthy businessman Mirza Ali Hasnain, a Japanese informant who was stabbed to death in his garden.

In the wake of Operation Jaywick, a 1943 Allied raid from Australia that sank six ships, the Japanese are alight with suspicion – though any number of people could have killed Mirza, from vengeful Chinese triads to one of his two taciturn daughters, or even the Japanese themselves.

One of the most endearing aspects of the original trilogy was its dry sense of humour. Yu is hard-pressed to find anything funny in one of the grimmest periods of Singapore history, but she does her level best to preserve Su Lin’s wry, sanguine voice.

She also retains her knack for converting careful historical research into lively details, like the Chens’ innovative ways of foraging for food during wartime.

Familiar characters are conspicuously absent. Half the original cast are either on the run or prisoners-of-war, including Chief Inspector Thomas Le Froy, Su Lin’s former police boss and mentor.

Though his whereabouts are shrouded in mystery, he remains a presence in the novel, as Su Lin constantly asks herself what he would do in her stead and Hideki, obsessed with his methods of investigation, views him as an arch-nemesis.

Yu turns her attention to figures not typically at the centre of WWII narratives, especially “collaborators” such as Mirza, Emily Bennington-Smith, an Englishwoman turned Japanese colonel’s mistress and, increasingly, Su Lin herself.

An orphan with polio who has long been an outcast among her own relations, she worries that helping the Japanese with their investigation will brand her a “running dog” – though, she reasons, it is not so different from her work with the British and it will save her family.

Recalling a Jesus-miracle play in which she was cast as a cripple, then replaced by an able-bodied girl, she muses: “I learned that fake miracles have hidden costs, but also that if you go along with the act, you get cake after the show.”

Nothing is black and white in this less buoyant, but nevertheless absorbing read.

If you like this, read: Lieutenant Kurosawa’s Errand Boy by Warran Kalasegaran (Epigram Books, 2017, $26.64, available at bit.ly/LKErrandBoy_WK), in which an eight-year-old Tamil boy is separated from his father and forced to work for the Kempeitai. Renamed Nanban, he learns the ruthlessness of his masters in order to survive.

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.

Source: Read Full Article