The 1960s may have been a wildly transformative decade in the history of popular music, but for Elvis Presley it was something of a black hole.

When he returned from his two-year hitch in the Army in 1960, the king of rock ’n’ roll essentially retired from live performing, confining himself to making movies (which were growing steadily worse) and recording disposable pop songs (that were no longer reaching the charts). A much-praised television comeback special on NBC in December 1968 had put him back on the radar. But when he finally returned to the stage for the first time in more than eight years, for a four-week engagement at Las Vegas’ new International Hotel, there was no guarantee he could still deliver onstage.

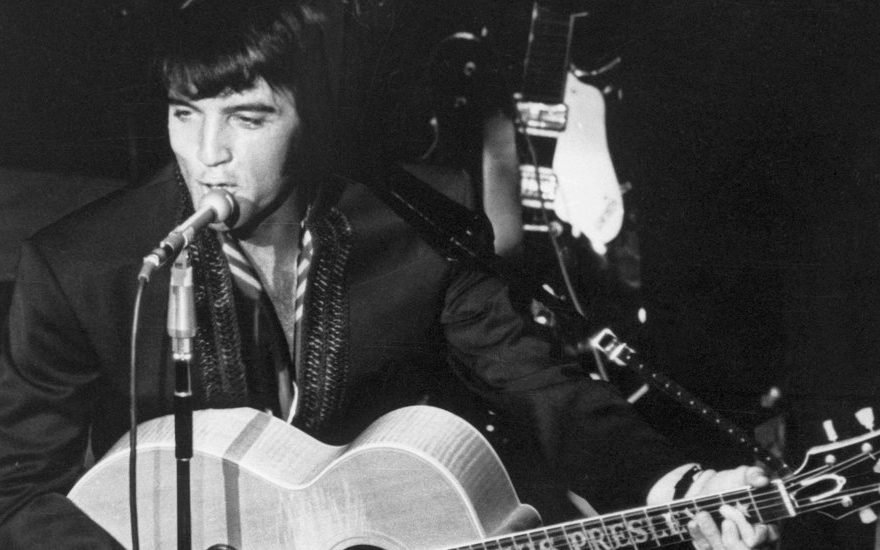

This week marks the 50th anniversary of Elvis’s Vegas comeback show, on July 31, 1969 — a milestone being celebrated by a new Sony 11-CD boxed set of his ’69 Vegas performances, a reunion concert in Memphis next month and probably some snickers from the rock classicists. Elvis’s Vegas years are mostly recalled as a period of commercial excess and artistic decline: the bombastic shows, the gaudy white jumpsuits, the ballooning weight, the erratic stage behavior, the drugs. “For many,” wrote Dylan Jones in “Elvis Has Left the Building,” “Vegas Elvis was already Dead Elvis.”

But for that 1969 comeback, and at least a year or two after, Elvis was at his peak as a stage performer, and he created a show that not only revitalized his career, but changed the face of Las Vegas entertainment.

The singer and the city had a long relationship. Elvis first appeared in Las Vegas in 1956, when he was just breaking out — he hadn’t appeared on “The Ed Sullivan Show” yet — and found himself booked into the New Frontier Hotel, on a bill with Freddy Martin’s orchestra and the comedian Shecky Greene. The show was pretty much a dud; the middle-aged nightclubbers didn’t know what to make of him. “For the teenagers, he’s a whiz,” wrote Variety’s critic; “for the average Vegas spender, a fizz.”

But Elvis loved Las Vegas, and the city became his favorite getaway.

He came back often: retreating there between movie shoots, seeing shows, picking up showgirls, partying all night with his Memphis pals. He shot his movie “Viva Las Vegas” there in 1963. He married Priscilla at the Aladdin Hotel there in 1967. So when his manager, Colonel Tom Parker, finally decided it was time for a return to the concert stage, Vegas was not as odd a choice as it might have seemed.

Las Vegas also needed a boost. At the beginning of the decade, with Sinatra and the Rat Pack riding high, the town was the white-hot center for live entertainment in America. By the end of the ’60s, however, the golden years were fading fast. The arrival of the Beatles, the rise of the counterculture — all of it was making Vegas look decidedly worn. None of the major rock artists of the era — the Stones, Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin — wanted anything to do with the city. The younger generation was going to arena concerts, not hanging out in the Sands Hotel lounge. So it was fitting that Las Vegas, a town blindsided by the rock revolution, would turn to a megawatt rock ‘n’ roll star as the agent of its reinvention two weeks before Woodstock would take place in upstate New York.

Elvis’s return to the stage in Vegas was a make-or-break career gamble. Colonel Parker had envisioned a traditional Vegas show, with chorus girls and choreography. Elvis wanted something different: a concert to reconnect him with his fans and showcase all the music he loved.

“This was the deprived musician, who had not been able to control his music, either in the recording studio or the movies,” said his longtime friend Jerry Schilling. “And now he was going to satisfy all his musical desires on that stage.”

Elvis handpicked a new backup band (headed by the guitar great James Burton), added two backup singing groups (a male gospel quartet, the Imperials, and a female soul group, the Sweet Inspirations, whose lead singer at the time was Cissy Houston), and filled out the sound with a 40-plus-piece orchestra.

The International’s 2,000-seat showroom was twice as large as any other in Vegas, and the sold-out venue was packed on opening night with celebrities and Vegas VIPs, along with dozens of rock journalists and critics, many flown in from New York on the hotel titan Kirk Kerkorian’s private jet. Behind the scenes, Elvis was so nervous he almost had to be pushed out onstage. “I saw in his face the look of terror,” said the comedian Sammy Shore, his opening act. But when Elvis walked out, to a throbbing rhythm intro, grabbed the microphone with a trembling hand, and launched into “Blue Suede Shoes,” the audience went wild.

It was the old Elvis, rocking as hard as ever, on a song he hadn’t done in a decade. He followed with more vintage hits — “All Shook Up,” “Don’t Be Cruel,” “Hound Dog”. He did them faster than in the old days, almost as if he wanted to get through them as quickly as possible, to get to the more mature and varied material he was starting to record. He sang “In the Ghetto,” the social-protest song that had been released in the spring and became a hit. He did covers of songs identified with other artists — Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode,” Ray Charles’s “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” the Beatles’ “Yesterday.”

The high point of the show was a galvanic, seven-minute version of a song almost no one in the crowd had heard before: “Suspicious Minds,” which would be released during his Vegas run and give him his first No. 1 hit in seven years.

The show lasted an hour and 15 minutes, and Elvis was on fire throughout — prowling the stage like a panther, doing karate kicks, sweating and downing water and Gatorade. He was huffing and puffing after just a few minutes, but the voice never faltered: richer, more expressive, more powerful than ever. “I never saw anything like it in my life,” said Mac Davis, the singer-songwriter who had written “In the Ghetto” for him and was in the audience that night. “You couldn’t take your eyes off the guy. It was just crazy. Women rushing the stage, people clamoring over each other. I couldn’t wipe the grin off my face the entire time.”

Presley talked to the audience too — nervously, with a few corny jokes and a lot of self-deprecating asides (much in evidence on the full-show recordings in the new boxed set). But that was part of the appeal: this was no slick Vegas performer with polished jokes and programmed patter. Elvis seemed just as awed by the occasion as everyone in the audience.

He played for four solid weeks, seven nights a week, two shows a night — not a single evening off — and every gig was sold out. The critics raved; David Dalton in Rolling Stone called Elvis “supernatural, his own resurrection.” Richard Goldstein, writing in The New York Times, said watching him “felt like getting hit in the face with a bucket of melted ice. He looked so timeless up there, so constant.” The hotel instantly signed him up for five more years.

Elvis brought something new to Las Vegas: not an intimate, Rat Pack-style nightclub show, but a big rock-concert extravaganza. He showed that rock ’n’ roll (and country and R&B too) could work on the big Vegas stage. And he brought in a new kind of audience: not the Vegas regulars and high rollers, but a broader, more middle-American crowd: female fans who had screamed for Elvis as teenagers, families who made Elvis the centerpiece of their summer vacation. It was the same audience that Vegas would discover, over the next couple of decades, as it embarked on its own reinvention — a foretaste of the Vegas we know today, the Vegas of Cirque du Soleil, theme-park hotels, and (more recently) a new generation of pop-star residencies, from Elton John to Lady Gaga.

Elvis soon grew bored with Vegas, and the shows began to deteriorate. But it’s easy to forget what an engaged, dynamic, even inspiring performer he was in 1969. Elvis in the ’50s had been the great divider: the musical artist who split the culture in two — between the adults, who listened to the pop standards and Hit Parade tunes, and the kids, who were listening to a newfangled music called rock ’n’ roll. By the end of the 1960s (a decade in which that divide grew even starker) Elvis was the great uniter: gathering all the music he loved, from rockabilly to operatic ballads, in one great democratic embrace. He didn’t need to be the coolest thing in rock. He wanted to sing to everybody.

He did. And in the process he helped transform a city.

Richard Zoglin is the author of “Elvis in Vegas; How the King Reinvented the Las Vegas Show,” just published by Simon & Schuster.

Source: Read Full Article