“He has created an entirely new phase of musical art and has produced a thoroughly American opera.”

The anonymous critic who wrote these bold words didn’t have a performance of Scott Joplin’s “Treemonisha” to evaluate, or a recording. In June 1911, all the reviewer had to go on was Joplin’s 230-page piano-vocal score.

Listen to This Article

For more audio journalism and storytelling, download New York Times Audio, a new iOS app available for news subscribers.

“Its production would prove an interesting and potent achievement,” the critic added, “and it is to be hoped that sooner or later it will be thus honored.”

It turned out to be decidedly later.

Desperate to prove himself in a genre he perceived as more serious than the ragtime piano pieces for which he was renowned, Joplin died in 1917 having tried again and again to mount “Treemonisha,” to no avail. His orchestrations and revisions, made with hoped-for stagings in mind, were lost.

It would be more than half a century before the opera finally premiered. When it did, its brilliance, shortcomings and unfinished aspects made it a work begging to be completed — giving creative artists room to experiment boldly with this “new phase of musical art.”

“Treemonisha” experiments seem to be everywhere these days: Three very different versions have recently been presented, in the United States, Canada and France. Their timing is a coincidence, and all were envisioned before the widespread calls for diversifying the canon over the past few years.

But after long development processes and pandemic delays, they have converged at a moment of intense interest in bringing back works by Black composers like Joplin, who was almost entirely forgotten until the ragtime revival decades after his death. “Treemonisha” languished even longer.

“Other than knowing the title, knowing it existed, I really didn’t know it,” the composer Jessie Montgomery, who collaborated with Jannina Norpoth on the orchestrations for a reimagining of the work that premiered in Toronto in June, said in an interview. But those days of even curious musicians being largely unfamiliar with the piece may be ending.

Set two decades after the Civil War among a group of free Blacks near the Texas-Arkansas border, the region where Joplin was born around 1867, “Treemonisha” is the sweetly stirring story of a young, educated woman who leads her community away from the influence of superstitious folk beliefs and toward a more enlightened future.

Today, the opera can feel a little prim, like a homily. The characters tend to be flat and stilted; the plot, sleepy and simplistic.

Treemonisha, the main character, doesn’t get enough good music. The use of heavy dialect, meant to distinguish her from the others, flirts with offensiveness. Joplin, who also wrote the libretto, made clear that his protagonist learned from a white teacher, furthering his crucial — and dated — theme: the need for Black people to cast off a racialized past and embrace an assimilation defined by whites.

Yet there are progressive, even utopian, aspects to the piece. At the end, Treemonisha — a woman, just 18 — is chosen as the community’s leader because of her strength, intelligence and empathy. When she demurs, suggesting she can care for the women, the men chime in and insist she take charge of them, too.

And in the score, Joplin pushed himself past ragtime into music that lilts, soars and swings with tenderness and vivacity, somewhat in the grand operetta style of Gilbert and Sullivan (if without the patter). He incorporates and recasts folk styles and popular dance in an artfully anthropological vein, like Dvorak in the “New World” Symphony of 1893, and includes some delicious tastes of rag, including the opera’s coup: its deliberately paced, steadily intensifying finale, “A Real Slow Drag.”

During Joplin’s lifetime, a performance in Atlantic City was planned and canceled; he played the piano for an informal showing in Harlem that led to nothing. His obsessive efforts were so stymied that one obituary said his death (from syphilis) was a result of “his failure to have the opera produced,” which “taxed away on his mind and resulted in a general breakdown.”

As his rags were rediscovered in the 1940s and ’50s, there was scattered talk of “Treemonisha.” But it wasn’t until the early ’70s that the opera was fully orchestrated — first at Morehouse College in Atlanta, in a version by T.J. Anderson for a small ensemble.

A watershed was Gunther Schuller’s beefier arrangement, which was used by Houston Grand Opera in 1975. There, the stage director Frank Corsaro conceived the piece as a dark but enchanting fairy tale. Louis Johnson’s choreography was rousing; the set, spare and symbolic — including a subtly suggested maypole for the tree under which Treemonisha is abandoned and discovered as a newborn, and for which she is named.

In Houston, when Treemonisha was kidnapped by the “conjure men,” the plot’s purveyors of superstitious bunk, the forest they take her to was a vision out of Sendak, with huge animal masks in the style of traditional African ones. The chief conjure man, Zodzetrick, was not the old man of the libretto but a slick showman-trickster, like Sportin’ Life in “Porgy and Bess.”

With Joplin suddenly mainstream after the runaway success of the 1974 film “The Sting” and its ragtime soundtrack, the Houston “Treemonisha” transferred to Broadway, to mixed reviews but enthusiastic audiences. In 1976, the country’s bicentennial, Joplin was awarded a special posthumous Pulitzer Prize “for his contributions to American music.”

After that, appearances of the opera often seemed like revelations — as at Opera Theater of St. Louis in 2000, when Schuller’s version was staged by Rhoda Levine.

“It looms so large in our company’s history,” Andrew Jorgensen, now the general director in St. Louis, said in an interview, adding that patrons still bring up memories of the cheering, notably diverse audiences. Jorgensen had been mulling over revisiting “Treemonisha” when, during the pandemic, Opera Theater presented a new one-act by the composer Damien Sneed and the librettist Karen Chilton.

After that performance, Sneed and Chilton mentioned their interest in the piece, and it was handed over to them. Their “Treemonisha,” which played in May and June, elaborates on the Joplin scholar Edward A. Berlin’s speculation, in his superbly researched biography, “King of Ragtime,” that the subtext of the opera is the composer’s tribute to his wife, Freddie Alexander, who died of pneumonia not quite three months after they were married, in 1904.

“It’s a science, exhuming something or reimagining something,” Sneed said. “And trying to refresh or rejuvenate it — trying to look at it through a new lens without taking away its essence.”

But sometimes the new lens does distract from the original’s essence. The St. Louis version turned the intriguing (if faint) subtext Berlin identified into a cudgel with which to beat the audience over the head. Sneed and Chilton framed “Treemonisha” — usually a succinct 90 minutes or less — with two overlong and overstated acts, the first depicting Joplin working on the score as Alexander’s health fades, the second with him alone and despondent after her death. The singers who played the couple became Treemonisha and her adoring friend, Remus, in the opera proper.

Sneed gamely inhabited a Joplin-like idiom in the newly composed material, but the vocal writing — a bit stentorian for Joplin, a bit gospel for Alexander — tended more toward strenuous exertion than Joplin’s decorous delicacy. And Rajendra Ramoon Maharaj’s scrappy production felt wan and underpopulated, even in the company’s intimate theater, though the baritone Justin Austin vibrated with passionate life as Joplin and Remus.

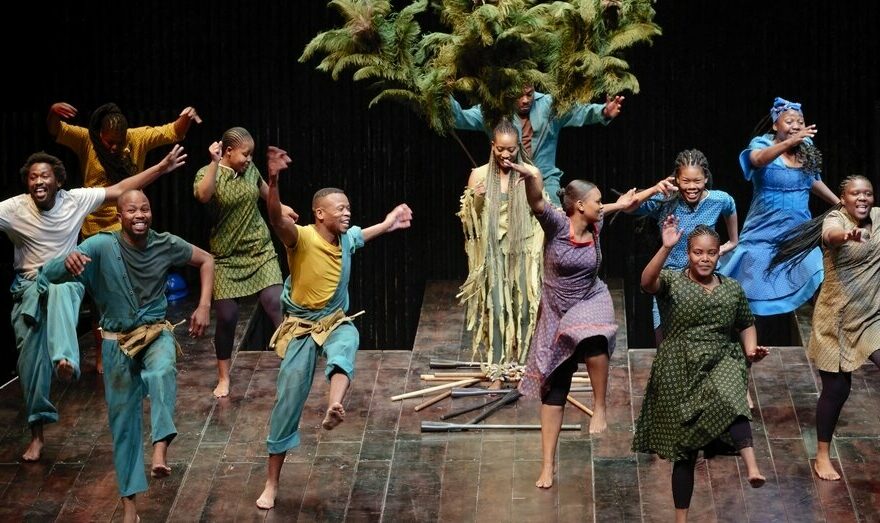

More stylized — and effective, and relevant — was the conception, in an entirely different sound world than Joplin’s, by the Isango Ensemble. The group, from Cape Town, specializes in recasting canonical works like “The Magic Flute” in the milieu and musical style of South Africa, and its “Treemonisha” (which I saw on a video capture of the premiere run, in Caen, France, in October) is a contemporary-dress but dreamlike spectacle of marimbas, drumming, traditional choral chant and whistling, and swaying, stomping dance.

“A lot of the issues in the piece are ones we still face here,” Mark Dornford-May, Isango’s director, said in an interview. “Issues of education, of deep sexism. There wasn’t a great leap for us from 1880s America on a plantation to today in a township.”

Particularly indelible are the images early on. The mystical tree is a performer sprouting a huge headdress of green plumage, visited by a skeleton hauled on the back of a puppeteer in black, who abandons the baby Treemonisha before she is found by her adoptive mother, Monisha.

“We wanted to show quite clearly that if Monisha doesn’t take that child, that child is going to die,” Dornford-May said. “And we wanted to make it very clear that it’s an extraordinary act of generosity. With the poverty in the townships — life expectancy of 49, TB rife, H.I.V. rife — with that sense of poverty, disease and death hanging over people, to take in another mouth to feed is extraordinary.”

Even more of an overhaul of the original was the version that played in June in Toronto, developed by the theater company Volcano with a core creative team of Black women: the book writers, arrangers, conductor and stage director. (It was presented by an unusually large set of institutional collaborators: the Luminato Festival and TO Live, in association with Canadian Opera Company, Soulpepper and Moveable Beast.)

The team took Joplin’s score, characters and setting, and grafted onto them a vastly revised plot, with the new words — by the playwright Leah-Simone Bowen, with Cheryl L. Davis — adroitly matched to the original rhythms and melodies.

Bowen and Davis take the “conjure men” more seriously and compassionately. They are now part of a community of “Maroons” — inspired by the Black people who lived in some Southern marshlands in the 19th century, and held Hoodoo spiritual beliefs linked to their roots in Africa — looked down on by Treemonisha’s circle of upwardly mobile, anxiously assimilationist freed Blacks.

“Depicting Hoodoo today as rooted in superstition and ignorance has no value,” Bowen said in an interview. “I wanted to explore how Treemonisha’s intelligence would be a tool she uses to understand that.”

Remus is now Treemonisha’s priggish fiancé, left at the altar and then a jealous villain; Zodzerick is the romantic lead who steals her heart and brings her back to her roots. The tragedy that transpires between the two men punctuates a richer plot than Joplin’s, as well as a more precise and moving parable of needless divisions between people with so much in common.

Montgomery and Norpoth, the composer-orchestrators, wanted the musicians to be visible onstage (as Isango’s are), so they settled on a chamber-size mix of strings and winds — and, deliberately, none of the piano so associated with Joplin and ragtime. Especially in the Maroons scenes in the forest, the arrangement makes haunting use of the kora — the West African string instrument whose player is often a kind of community bard — and African percussion, for a landscape that feels both mysteriously distant from Joplin and surprisingly friendly to him.

There are reworked songs from Joplin’s score, as well as some melodies borrowed from his art songs, and some changes in the order of numbers. “Some of it goes pretty far from what Joplin usually sounds like,” Norpoth said in an interview, “but all of it is based on his themes.”

She added that the creators hoped to carve out even more space for improvisation and kora solos, and to forge deeper links between the African instruments and the rest of the ensemble. But this production, like Isango’s, feels ready to be seen more widely.

Both shows are seeking presenters in a tough environment for the performing arts, especially big, ambitious touring projects like these. Both should be supported as sterling examples of how art of the past can take on new life in a new era.

Audio produced by Tally Abecassis.

Zachary Woolfe became The Times’s classical music critic in 2022, after serving as classical music editor since 2015. Prior to joining The Times, he was the opera critic of the New York Observer. More about Zachary Woolfe

Source: Read Full Article