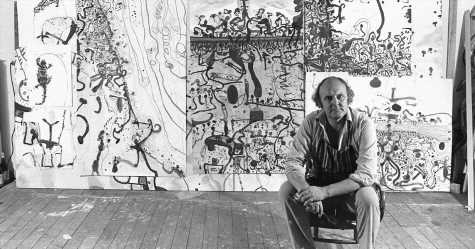

John Olsen, an artist who helped shepherd in Australia's postwar modern art movement and whose exuberant, vivid and abstract depictions of the Australian landscape redefined the way the country saw its natural environment, died on April 14 at his home in Bowral, New South Wales. He was 95.

His death was announced by his children, Tim and Louise Olsen, in a statement. Tim Olsen is also his father’s gallerist.

A landscape painter who in his youth rebelled against the cultural establishment, Mr. Olsen was among the generation of artists who first defined Australian modern art. As the last surviving member of that generation, he was often called the country’s greatest living painter.

“Olsen is literally the last man standing of that grand generation of Australian artists who created modern painting from the ground up: the men and women who quit the country to tour Europe and return home later with big ideas and matching ambition,” Andrew Frost of The Guardian wrote in 2016.

His works, known for their vivid explosions of color, their fluid, coiling lines and their aerial perspective, have sometimes invited comparisons to Australian Aboriginal art. They challenged the prevailing landscape painting tradition, which saw Australia’s vast desert center as lifeless and empty.

“We’ve got the richness of emptiness which for some reason was known as the dead heart,” Mr. Olsen said in 2016 at the opening of a major retrospective of his six-decade career. “That’s a lie. That’s not true. It’s teeming with life. And this kind of thing is an exciting thing. To be an Australian artist is to be an explorer.”

John Henry Olsen was born on Jan. 21, 1928, in Newcastle, an industrial town in New South Wales, the older of two children. His father, Henry, was a clothes buyer; his mother, Esma (McCubbin) Olsen, was a tailor.

He grew up during the Great Depression in a family that had little in the way of books or art. But from a young age, he loved to draw on any surface he could find, including the pages of his mother’s cookbooks.

Wanting to escape the tedium of a sales job, he enrolled in art classes when he was 19. He studied at several schools in Sydney — the Dattilo-Rubbo Art School, the Julian Ashton Art School and the East Sydney Technical College — while working as a freelance cartoonist and a janitor to support himself.

As a student, he joined a movement that railed against the staid mainstream tradition of figurative painting. In 1953, he was the spokesman for a demonstration of about 30 youths against the Archibald Prize, Australia’s most prestigious portrait award, complaining about its stuffy conservatism after the prize was given to the same artist for the seventh consecutive year.

In 1956, he took part in a group show called “Direction 1.” It was a “critical and commercial failure, receiving tepid responses and zero sales,” the author Darleen Bungey wrote in her biography, “John Olsen: An Artist’s Life” (2014). But the exhibition was later credited with bringing Abstract Expressionism to Australia.

Mr. Olsen’s early work drew the attention of Robert Shaw, a wealthy businessman, who paid for him to go to Europe for three years. There, his study of Spanish artists crystallized his understanding of painting as not just depicting a scene but being “about a feeling, emotion and an experience,” Steve Alderton, director of the National Art School in Sydney, formerly the East Sydney Technical College, where Mr. Olsen studied and later taught, said in an interview.

He brought this ethos back to Australia in 1960, painting a series of joyfully extravagant landscapes called “You Beaut Country” that propelled him to mainstream fame. The series “exploded the stereotypical view of the landscape as a placid ensemble of sheep and gum trees,” John McDonald of The Sydney Morning Herald wrote in 2007. “Suddenly the bush became a joyous place, bursting with life and incident.”

His most high-profile work was “Salute to Five Bells,” a 1973 mural commissioned for the Sydney Opera House. A 68-foot-long work in which sketches of landmarks, sea creatures and symbols float on an ocean of blues and purples, it was unveiled by Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip while they were touring Australia. When Mr. Olsen explained to the royal couple that the work was “about Sydney Harbor,” Prince Philip asked, “Where’s Luna Park?,” referring to the harborside amusement park.

The work also received a mixed reception from Australians, some of whom considered it too muted and too sparse in detail. Over time, however, it has become one of his most well regarded works.

In his later years, Mr. Olsen continued to paint Australia’s interior, regularly driving or flying across the country in search of inspiration. But he also turned his gaze inward with more somber, introspective works. In 2005, he won the Archibald, the prize he had protested in his youth, with “Self-Portrait Janus-Faced,” a painting Mr. McDonald of The Morning Herald called “a moving, complex picture that turned a cold eye on age and mortality.”

Mr. Olsen’s artistic success was tempered by a turbulent personal life. He was married four times, to Mary Flower, Valerie Strong, Noela Hjorth and Katharine Howard. The first three marriages ended in divorce. Ms. Howard died in 2016. He had one child with Ms. Flower, Jane, who died in 2009, and two children, Tim and Louise, with Ms. Strong. In addition to them, he is survived by four grandchildren.

Mr. Olsen died just seven weeks before his works were to be projected onto the sail-like roofs of the Sydney Opera House in a celebration of his career. His children said he had been looking forward to the exhibition.

“I can watch my work on the Opera House sails in my own private light show in a beautiful hotel room with my family all around me, before going to bed and quietly drifting off forever,” he told them, according to their statement. “What better way to say goodbye?”

Source: Read Full Article