PBS has reached into its vault and retrieved “Goin’ Back to T-Town,” a 1993 “American Experience” documentary whose broadcast Monday night is doubly timely. It marks the 100th anniversary later this year of the Tulsa massacre, the deadly and massively destructive race riot that remained little known when the film was made but lately has re-emerged as a supremely ugly scar on the American conscience.

It also honors the career of the veteran Black filmmaker Sam Pollard, who produced the movie with his wife, Joyce Vaughn. After working under the radar for nearly 50 years, he’s currently being celebrated for a new documentary “MLK/FBI.” His latest project, “Black Art: In the Absence of Light,” premieres Tuesday on HBO.

Working with a team that included Black artists like the writer Carmen Fields, the cinematographer Robert Shepard (“Freedom Riders” (2011), “Eyes on the Prize”) and the actor Ossie Davis as narrator, Pollard and Vaughn tell their story concisely and elegantly, in the traditional chiaroscuro-interview style of PBS history documentaries, but with a twist.

No outside historians or experts appear — the film rides entirely on the voices and faces of about 15 Black residents of Tulsa, Okla., some of whom were eyewitnesses to the events of May 31 and June 1, 1921, when a white mob burned to the ground the 35-square block Greenwood neighborhood and killed up to 300 Black Tulsans. (One of the interview subjects, John Hope Franklin, who moved to Tulsa shortly after the massacre, went on to become a leading scholar of slavery and American racial injustice.) It’s an approach that couldn’t be duplicated now, when nearly all the survivors of the massacre have died.

The film may subvert the expectations of a contemporary audience in a more fundamental way as well. The violence itself, vividly depicted in recent dramas like “Watchmen” and “Lovecraft Country,” is not the dramatic focus of “Goin’ Back to T-Town.” The film’s account of it, from the accidental contact of a Black man and a teenage white girl to montages of smoking ruins and corpses lying in the street, occupies about 10 anguishing but subdued minutes halfway through.

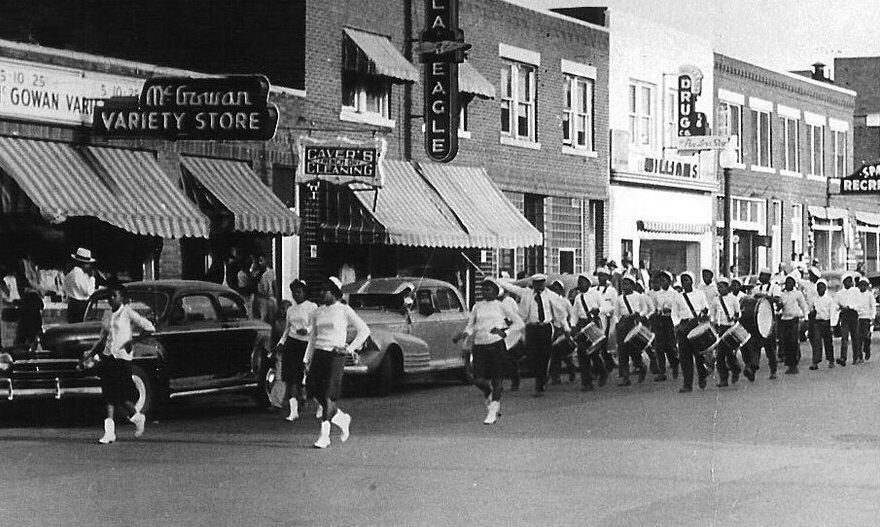

Pollard and Vaughn are telling a larger story. It begins with an inspiring, deceptively cheerful account of the growth of Greenwood, the largest of a number of all-Black communities in Oklahoma. “The whole shootin’ match was there,” one survivor recalls, and the camera scans a business directory listing Black hotels, insurance agencies and “The Williams Grocery, for race pride.” By 1921 the 11,000 Black residents of Tulsa could live safely inside an enclave with 15 grocery stores, four drugstores, two cinemas and two public schools of their own. But the Ku Klux Klan was nearby — just four blocks away “on Main and Easton,” a resident recalls.

And the film spends its second half on the post-massacre history of Greenwood, which was rebuilt and remained a Black neighborhood without regaining its former prosperity. It’s a sad and complicated story, in which the parallel society created by Black residents and businesspeople was doubly cursed: first a seemingly inevitable victim of racist resentment and violence, and then, after national battles against segregation were won in the 1950s and 60s, a victim of depopulation and economic blight. “We got integration — and suffocation and degradation and all the other ’ations you would like to have,” a longtime resident says.

The tone of “Goin’ Back to T-Town” is elegiac, and its chorus of mostly elderly witnesses is impeccably dignified — they’re clearly carrying out a duty, and their anger and pain, while right on the surface, are never indulged. The film ends with their memories, and a last rush of images, of a halcyon time of nothing but normal life: football games, shopping, dinners out. Unsaid but manifest is how unequal that separate life always was, and how fleeting and fragile the happiness it brought.

Source: Read Full Article