There’s something about a writer pausing to reflect on a career 35 years strong that sets the reader up to expect an avuncular figure, tossing lines of wisdom from on high. What a pleasure it is, then, to get halfway through the first essay in Haruki Murakami’s new collection and find him arguing that experienced novelists are largely generous to newcomers because they know most of them won’t last more than a few books, a fact that makes it easy to be welcoming.

The essay is called, darkly, Are Novelists Broadminded? Avuncular, Murakami? I should have known better. But he does have such a friendly way of going about his sentences that you fall for his charms every time. It’s easy to forget that for every one of his novels’ placidly indelible images – of a man meditating down a well, or preparing a simple meal for one – there’s a description of a person being skinned alive.

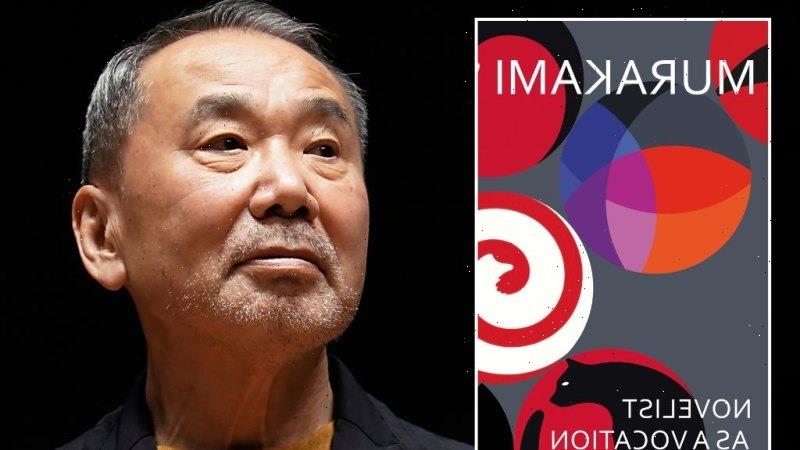

Haruki Murakami thinks his novels surge in popularity from country to country at times of national upheaval.Credit:AP

Murakami has already written a non-fiction book beloved by writers for its elegant argument about the relationship between writing and the body, 2008’s (in English) What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, in which Murakami contends, while tracing his marathon habit, that “most of what I know about writing I’ve learned through running every day”.

By contrast, Novelist as a Vocation is an inelegant volume, composed of pieces he wrote for a magazine, plus extras. It has no central idea, save that Murakami has been doing what he is doing for a long time, and its many arguments are not always strong. In my view, it’s the kind of book more writers should publish late in their careers. It’s venal, particular, experienced, sharp. It is a weird delight.

Haruki Murakami’s Novelist as a Vocation.

Just as it lacks a central argument, it lacks an emotional core. Instead, it’s tethered to the past as if by a piece of emotional gristle, the point in Murakami’s life when he owned a jazz club and didn’t yet write full time. It’s like one of those inflexion points in the novel 1Q84 (published in 2011 in English) when the world stops being one way and starts being another.

In one possible world – our world – Murakami comes to play a singular and curious role in international literature. Was the role of literary-popular-philosophical-experimental-fabulist-translated-bestseller even imaginable before Murakami? The author is succinct and brilliant in his analyses of this role, in an essay discussing his early choice to prioritise the American market and tracing its impact on his career. He thinks his novels surge in popularity from country to country at times of national upheaval, when people need to reassess the foundations of reality.

But we’re always in the presence of another world, where Murakami never became this writer. There is a publisher-sponsored prize Japanese called the Akutagawa Prize that he was apparently tipped to win early in his career, and then didn’t. It may read strangely to Australian readers, where we don’t have a prize that plays an equivalent role as a predictor of writerly viability or reputation. But it’s intriguingly unpacked as a sort of foundational trauma, not so much because he didn’t win, but because he was drawn into a complex web of other people’s interpretations. It’s about rejection, expectation, and approval; in other words: all the messy stuff that is familiar to anyone who does any kind of work.

He writes from a similarly raw nerve – 35 years later! – about some of his early critics. Such writing can be uncomfortable – it’s not very heroic – but its unevenness and vulnerability leaves this set of essays with a sense of haunted retrospection.

There are parts of the book I could have done without, the prime offender being an essay about originality that spends a lot of time making the point that originality is contingent on time and context, complete with the predictable musical references.

But then five pages later, out of nowhere, there’s this: “if you want to express yourself as freely as you can, it’s probably best not to start out by asking ‘What am I seeking?’ Rather, it’s better to ask ‘Who would I be if I weren’t seeking anything?’ and then try to visualise that aspect of yourself.”

It’s surprising and practical, singular and strange, and this collection is studded with wisdom just like it.

Novelist as a Vocation by Haruki Murakami is published by Harvill Secker, $35.

Ronnie Scott’s second novel, Shirley, will be published by Hamish Hamilton in February.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from books editor Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article