Mariah Carey’s new book makes it official: We are in the golden age of the celebrity memoir.

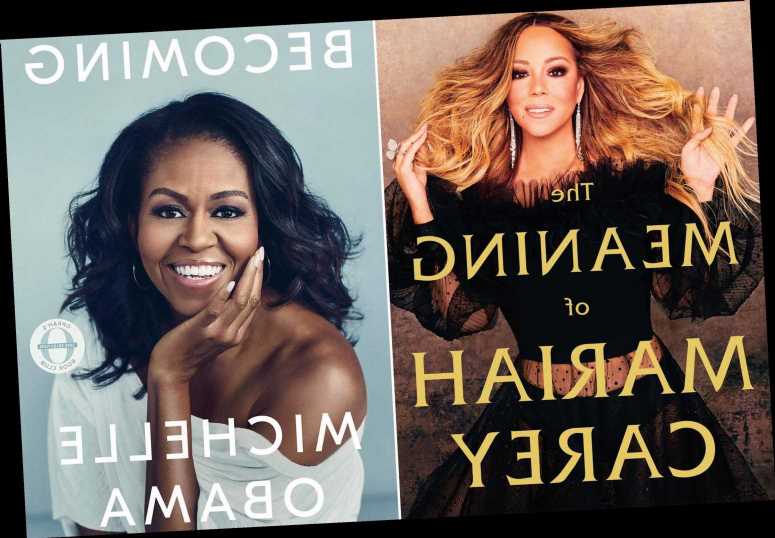

“The Meaning of Mariah” — published Tuesday and already a critically acclaimed best seller — follows three recent, blockbuster confessionals by female superstars: “Inside Out,” by Demi Moore, “Open Book,” by Jessica Simpson, and Michelle Obama’s “Becoming.”

All four women have broken barriers. Carey holds multiple Guinness World Records, including the most No. 1 songs of any solo artist. Moore became the world’s highest-paid actress when she signed to do 1996’s “Striptease” for $12.5 million (an achievement that earned her the sexist appellation “Gimme Moore”). Simpson’s fashion and accessories line brings in $1 billion annually. Obama, of course, went into the history books in 2008 as America’s first black first lady.

Yet each woman, in her memoir, has gone deeper than she had to, inviting fans, casual observers and the merely curious into complicated and painful parts of her life. Why risk sharing so much, especially since social media is the cheapest, quickest and most curated way to control one’s image?

Celebrity memoir, it should be noted, isn’t for the weak. Mick Jagger, Billy Joel — even Oprah Winfrey, mother of Confessional Culture — have all returned massive advances rather than go through with writing their own.

For those stars who go all in, however, the chance to tell their stories, unmediated and unfiltered through any lens but their own, is a powerful lure.

“I think that a book gives a person control over their narrative in a way that no other medium really does,” said literary agent Nicole Tourtelot, who has worked with celebrity authors. “The connection between writer and reader is so direct, so intimate. And I think that’s particularly compelling for people who are constantly photographed, written about, talked about and whose image is created, in a way, via the public perception and conversation. To be able to fully explain oneself and have hours of undivided attention to craft your own narrative is an irresistible opportunity.”

Memoir is also, as Demi Moore told the New York Times, a way to work through who one was, and has become, without the attendant noise of tabloid and social media. “Inside Out,” Moore said, wasn’t so much about re-entering the spotlight as it was reclaiming her narrative.

“It’s more of an awakening,” she said of her book, “than a comeback.”

“I don’t think the analogies between memoir-writing and therapy are wrong,” said one celebrity ghostwriter who has helped several stars pen New York Times best sellers. Writing a memoir, she said, “give[s] all the things that happened to you a structure and a meaning. You can see patterns.”

Moore wrote about having been raped at age 15, leaving home at 16, youthful hookups with Rob Lowe and Jon Cryer, an early-stardom intervention over her drug use and her three marriages — including humbling stuff about her last, to the much-younger Ashton Kutcher. Moore describes having lost a six-month pregnancy during that marriage, her subsequent relapse into drug and alcohol addiction and succumbing to a threesome in hopes it would stave off divorce.

For those of us who grew up watching Moore boldly push against societal constraints — her 1991 Vanity Fair cover, for which she posed pregnant and nude, was, at the time, truly scandalous — such revelations weren’t just heartbreaking. They showed a beating heart beneath the steely veneer.

“I wanted to show him how great and fun I could be,” Moore writes of her self-abasement. “[I] went into contortions to try to fit the mold of the woman [Ashton] wanted his wife to be.”

Many a woman can relate. And what a balm to be reminded that fame and fortune insulate no one from life’s indignities. Moore, at 56, reinvented herself by revealing herself.

Obama, in her memoir, went where no former first lady had before, opening up about her parents’ views on sex, her own fertility struggles, a miscarriage, conceiving both of her daughters through IVF and attending marriage counseling.

Simpson — whose memoir was called “mesmerizing” by no less than the New Yorker — wrote about being sexually abused as a small child, the self-described psychological abuse she suffered from on-and-off boyfriend John Mayer, her addiction to alcohol and sleeping pills and a near-lifelong battle with weight that began in 1997, at age 17, when record company executive Tommy Mottola told her: “You’ve got to lose 15 pounds,” demanding six-pack abs after her first single hit the charts.

Interestingly, Mottola also figures as a villain in Carey’s memoir. Here, the self-described “elusive chanteuse” reveals more about her marriage to Mottola — long rumored to be controlling and abusive — than ever before. She also writes about her traumatic childhood as the daughter of a black father and white mother, of her sister allegedly pimping her out as a 12-year-old girl, and of the time her then-husband Mottola allegedly put a knife to her cheek, threatening her looks and her livelihood, followed by her liberating affair with Derek Jeter.

Among other secrets.

For millions who love the genre, myself among them, it’s been interesting to watch this sudden spate of celebrity memoirs raise the bar — not just in terms of candidness but also quality. Obama, Moore, Simpson and Carey each worked with distinguished ghostwriters to produce not just best sellers that would generate headlines, but books that are highly readable and immediately entered the canon. (The ultimate modern celebrity memoir, for me, is Patti Smith’s “Just Kids” — novelistic in its evocation of artistic strivers in late 1960s and ’70s New York.)

“People’s flaws are what make them lovable,” the ghostwriter said. “I think we love celebrities more if we know that they have suffered or screwed up than we would if they were just happy, perfect Barbie dolls” — in essence, the opposite of most social-media avatars.

The process itself has built-in guardrails: The celebrity speaks to her ghostwriter and editor in full confidence, and at the end can delete anything she’s uncomfortable with before publication.

But most celebrity authors no longer censor themselves much.

“As a culture, we’re moving away from wanting our heroes and celebrities to be perfect,” Tourtelot said, “and are much more responsive to celebrities who show us a human side. Social media has brought down the veil and created a culture of self-disclosure. So either it’s made it more professionally acceptable for celebrities to reveal all of themselves, warts and all, or it’s raised the bar on the level of disclosure we expect as fans. Maybe both.”

‘As a culture, we’re moving away from wanting our heroes and celebrities to be perfect.’

The ghostwriter agrees. “I think when they see it all written up in their own voice, the things they’d been hiding often seem more like valuable, relatable stories than like shameful secrets.”

Our most recent proof: The glamorous Mariah Carey, as controlling of her image as Barbra Streisand — both divas have long insisted on only side of their face be photographed — writes openly of a destitute and dangerous childhood, one that shaped her more than anything.

As she recalls in her memoir, writing of a time police were called to her troubled home when she was just 6 years old: “One of the cops, looking down at me but speaking to another cop beside him, said, ‘If this kid makes it, it’ll be a miracle.’ And that night, I became less of a kid and more of a miracle.”

Share this article:

Source: Read Full Article