They’ve lived through war, terrorist attacks, and now, a pandemic. This is how New York’s resilient senior citizens are coping with the stay-at-home order — and staying positive in the process.

Post photographer Tamara Beckwith observed New Yorkers living in lockdown for The Post’s photo special, “Apart Together.”

Al Black, 80, Harlem

Before New York’s self-quarantine went into effect, Black could be found almost every night of the week playing trumpet at the Paris Blues jazz club beneath his apartment on West 121st Street. Now he plays the horn out of his open window for the neighbors.

“Music is really uplifting for the soul,” says Black, a karate black belt whose daily concerts involve harmonizing with a saxophone player who lives down the block. “We want to help cheer everyone up. I feel we are going to come out of this.”

Mary Ellen Curran, 78, Bay Ridge

“The only thing that keeps you going now is your faith,” says Curran, who logs onto Facebook at noon every weekday to attend live-streamed mass from St. Patrick’s Church in Brooklyn. She has two children and three grandchildren and is currently staying alone in a Bay Ridge studio apartment.

“I wave out the window to my son,” she adds. “You get very anxious. Is it going to hit you or your family?”

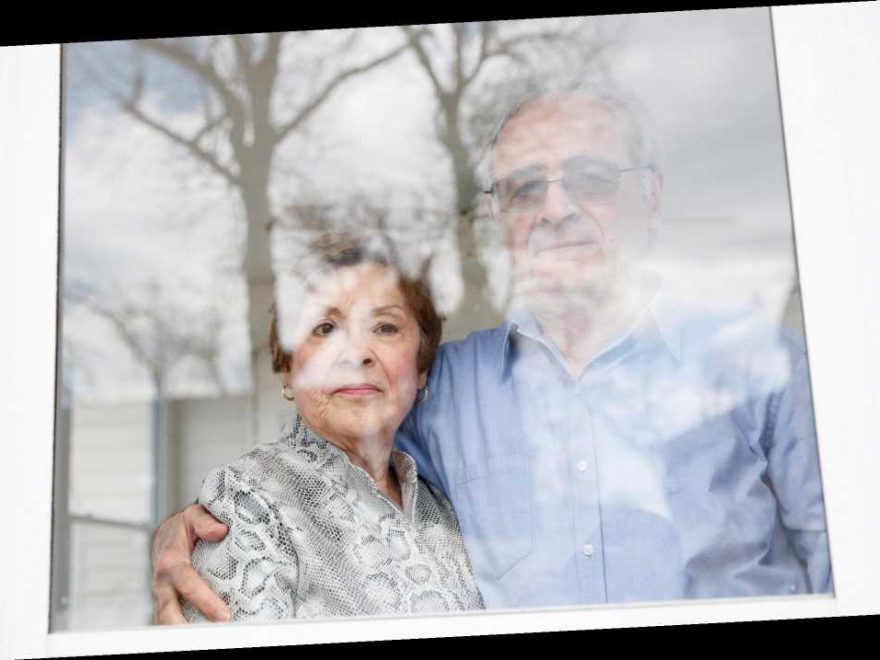

Mary Grace, 75, and Dominick Sileo, 78, Annadale, Staten Island

The coronavirus pandemic brings up memories of Sept. 11 for Mary Grace, who worked for the Port Authority in the World Trade Center at the time but by coincidence did not go to the office on that fateful day. She mourned 14 of her co-workers.

“It’s very easy to go into that dark place. I have to change the channel in my thoughts and count my blessings,” says Mary Grace, who is keeping busy by taking virtual Zumba classes and crocheting a red, white and blue throw. “I haven’t crocheted in 40 years!”

With Dominick, a retired cartoonist, she is also shredding old documents, hanging a new chandelier and brightening up a wall with a new mural of a Tuscan landscape.

Jane Varkell, 81, Greenwich Village

Varkell, who has a breathing condition, started self-isolating in her sixth-floor apartment on March 6. Although she calls the separation from family “a challenge to get through,” she walks a mile a day inside her apartment and plays bridge with her formerly in-person bridge club via Zoom.

Tending to her plants is another heartening activity. “I have a lot of sunlight in the apartment,” Varkell says. “I love orchids. I always have one white orchid.”

Carlotita, 85, and Carlos Ayala, 89, Castle Hill, Bronx

“I came here alone in 1960 from Lima, Peru. I had to do whatever I had to do in order to survive,” says Carlos, a retired accountant. “This is scary. I have seen nothing like this.”

While he has turned to more traditional stay-at-home distractions, like television, his wife Carlotita has taken to stitching together purses out of scraps of fabric she’s found around the house. “I used to go to the gym every day,” says Carlotita. “Now sewing is my life.”

She and her husband used to enjoy playing the penny slot machines at Foxwoods Casino in Connecticut or in Atlantic City, New Jersey. “Last time, I lost,” she recalls. “So maybe it’s better! If I can’t go, it’s OK.”

Asia Shindelman, 91, Wayne, New Jersey

Shindelman — who is a survivor of the Stutthof death camp in Poland — spends her housebound days reading books, watching the news in English and Russian and talking to her two sons, four grandchildren and five great-grandchildren on the phone.

“At the end of my life I never expected to see anything like this,” she says. “We have to be patient. We cannot lose our hope. If I didn’t have hope, I wouldn’t have survived [the Holocaust].”

Ann, 70, and Joe McDermott, 82, Douglaston, Queens

The executive director of the nonprofit Consortium for Worker Education, Joe is working full-time from home to help anticipate and alleviate the challenges — from hunger to internet access — many New Yorkers will face as the isolation order continues. “We feel privileged here,” Joe says. “This whole thing did expose the inequality of resources.”

Ann, a retired photographer, is cutting plastic to make face shields for hospital staffers who lack personal protective equipment (PPE). “We have to do what we have to do,” she says. “It’s going to be a long haul.”

Source: Read Full Article