In Todd Snider’s mind, the most unusual aspect of Jason Isbell and Amanda Shires’ wedding in 2013 wasn’t that Snider was asked to marry them or that he wasn’t legally ordained to do so until that day. It was what Snider was asked to recite: “Prayer,” an obscure song by the late John Hartford. “Every morning I wake up,” it begins, “Saying in the back of my mind/’This could be my last day on earth/This could be the last time/I’ll ever feel … the warmth of your flesh next to mine.’”

“Everyone giggled,” Snider recalls. “Her parents were laughing. His parents were laughing. That was a cool wedding.”

That irreverent moment was also an indication of the high regard in which Hartford, who died in 2001 from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma at 63, is regarded by the country world’s old and new guard. A singer, songwriter, banjo player, fiddler, music curator, and one-time TV personality, Hartford remains best known for writing “Gentle on My Mind,” which effectively launched Glen Campbell’s career.

But Hartford was also a licensed riverboat captain, a pioneer of the prog style of bluegrass that came to be called “newgrass,” an indie label businessman-rebel, and, as Snider says, “a troubadour from the jam scene, a hippie-stoner part of the world I live in.” Hartford’s’ “Don’t Leave Your Records in the Sun” cautions against the damage that can be inflicted upon vinyl when left outside for other purposes — unspecified, but presumably from rolling joints. “All the stoners get the humor in that song,” Snider says.

Related

Hear Band of Heathens Cover John Hartford's 'Up on the Hill' for New Tribute Album

Glen Campbell: 20 Essential Songs

Related

Stopping Short: 10 'Seinfeld' Episodes You Forgot You Loved

New Doc on INXS' Michael Hutchence: 12 Things We Learned

In the last few years, Hartford’s profile has once again spiked, after his 1967 deep cut “This Eve of Parting” was featured in Greta Gerwig’s acclaimed Lady Bird. “It was a song Greta felt strongly about throughout the editing process,” says Michael Hill, a music supervisor on the film. “It had such emotional resonance in those scenes, and it really worked with Laurie Metcalf’s character. One would typically put score there, but Greta instinctively knew that song would work.”

Continuing the rediscovery of his work, Hartford will be the subject of two simultaneously released tribute albums, both out June 26th. On the Road: A Tribute to John Hartford includes covers of his songs by Snider, John Carter Cash, Sam Bush, the Yonder Mountain String Band, Railroad Earth, Leftover Salmon, and others. Proceeds from the album go toward helping virus-affected musicians by way of MusiCares.

The John Hartford Fiddle Tune Project, Volume 1 is a collection of never-recorded instrumentals Hartford was writing before his death. Culled from a slew of annotated notebooks he kept — and published in conjunction with a book of those songs and writing, John Hartford’s Mammoth Collection of Fiddle Tunes — the album includes the first recordings of those compositions by, among others, mandolinist and new bluegrass star Sierra Hull, mandolinist Ronnie McCoury, banjo player Mark Howard, and producer and fiddler Matt Cobbs. Both projects also aim to remind people of the often forgotten scope of Hartford’s work and life. “A lot of people know ‘Gentle on My Mind’ but they don’t know where it came from,” says Cash. “It’s like ‘Send in the Clowns’ in that way. Some people only know Sinatra’s version, but they didn’t know that Sinatra didn’t write it.”

Hartford foretold the path of his career right from the start. The first song on his debut album, 1967’s Looks at Life, starts with rippling banjo before Hartford enters, talking about “this demon called commercial” that looks to lure in “struggling young artists” who succumb to the monster. It’s his version of David Bowie’s “Fame” — but, in Hartford’s case, before the fame.

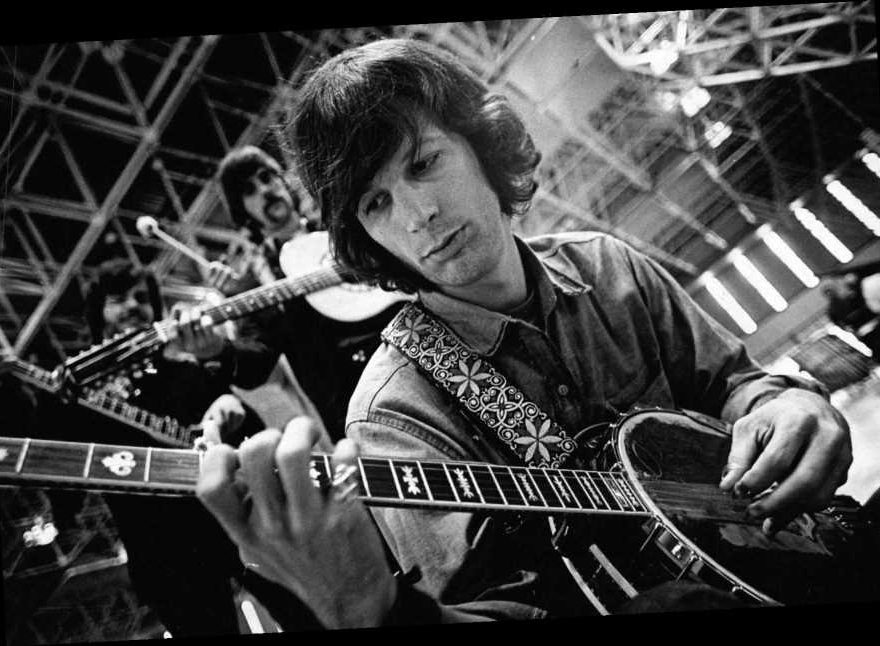

Born and raised in St. Louis in 1937, John Cowan Harford didn’t appear destined for pop or country charts. As a teenager, he began playing fiddle at square dances, eventually moving to five-string banjo. He was pushing 30 by the time he, his wife, and young son moved to Nashville in 1965, where he attempted to make a living in the music business. He did studio work (including on the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo in 1968), signed a publishing deal, and became a DJ to pay the bills. His publisher introduced him to Chet Atkins and producer Felton Jarvis, and Harford — now renamed Hartford — wound up with an RCA contract in 1966.

Hartford’s earliest albums for the label are some of the most idiosyncratic released in Nashville in the Sixties. On them, you’ll hear deadpan novelty songs, unconventional protest tunes (the anti-nuke “When the Sky Began to Fall”), and transcendent, strings-decorated ballads like “This Eve of Parting,” written when he was about to go on tour and leave his wife behind. “I’ve been really inspired by his ability to be so open,” says Sierra Hull, who was 9 when Hartford died and only recently discovered his music. “I don’t think there would be anything from John that would seem surprising, because there was no box he was in. If it was something he was interested in, he would explore it to the fullest degree.”

In 1966, Hartford and his wife went to see Dr. Zhivago, the romantic epic set in pre-World War I Russia. Hartford was so affected by the experience that as soon as he arrived home, he wrote “Gentle on My Mind” in 20 minutes. The song was inspired by his marriage — but also possibly by the movie. “I once asked him, ‘John, how’d you write that song?’” recalls McCoury, the son of bluegrass legend Del and a friend and collaborator of Hartford’s. “He said, ‘Well, I watched Dr. Zhivago and I walked out of that theater and I wanted to drink Julie Christie’s bathwater!’”

Hartford cut the song first, but it was Glen Campbell’s version that made it a standard. In 1967, both men won separate Grammys for singing or writing it. (Hartford won for Best Folk Performance and Best Country & Western Song, and Campbell for Best Recording and Solo Male Vocal Performance, both in the country category.) But no one, not even Hartford, could have predicted what came next.

Tom Smothers, then co-hosting The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour with his brother Dick, was smoking weed one day with musician and series regular Mason Williams, both listening to one of Hartford’s albums. According to author David Bianculli, the idea of having Hartford on their show popped into their brains right then. Before long Hartford was appearing on the hippest and most envelope-pushing variety show of its time. “There would be this guy playing banjo on major network television,” recalls McCoury of watching the show when he was young.

Moving to L.A. with his family, Hartford was also hired as a writer for the Smothers’ series and was a regular on Campbell’s own variety show starting in 1969. “My mother tells stories of going on writing retreats [for the Smothers] and there was Steve Martin or Rob Reiner,” says his daughter Katie Hogue. “It was kind of wild.”

Lanky, droll, and leanly handsome, Hartford seemed a natural fit for TV and film roles. “The agents out there, they want to put you in everything they can,” says Hogue. “They wanted to drum up exposure. He was under the control of the whole commercial thing, with record companies and agents.” Hogue says her father was considered for a role in the movie True Grit — possibly the one that eventually went to Campbell — but turned it down because “he wasn’t an actor.” Hartford did, however, host a short-lived variety show of his own, Something Else, where he drove and ambled around L.A., introducing musical guests and actors with markedly low-key energy.

Hartford barely hid his ambivalence toward the show-biz world that wanted to make him a down-home star. “People are always asking me, ‘How does it feel to be a star?’” he said in 1969. “I don’t like the word. I’m not into the whole entertainment business game. … I’d rather have the song well known than myself well known.” He turned down an offer to rewrite the lyrics for “Gentle on My Mind” for an ad and called writings songs for other artists “a pretty gruesome affair.”

From all accounts, the period brought Hartford success but also turmoil. He and his wife split in 1970, soon after the arrival of their daughter Katie. His family returned to Tennessee, and Hartford followed them back, effectively ending his Hollywood period. “Maybe his heart said, ‘I don’t want to be in the limelight anymore,’” says Cash, who became friends with Hartford during the last years of Hartford’s life. “It can be confusing. Some of my best friends are famous and lot of them are grounded. But a lot of the sway back and forth — my father was one of them. Maybe John swayed out and thought, ‘I have to sway back the other way.’”

Switching labels to Warner Brothers, Hartford cut 1971’s Aereo-Plain, a loose, freewheeling, and eclectic album that reinvented bluegrass for a new, post-rock generation. It also mocked rock clichés in the hilarious “Boogie.” “Aereo-Plain changed my life,” says Cash. “It’s so avant-garde and so different. There no rules on that album.” Still dissatisfied with major labels, Hartford shifted to indie labels and even quirkier albums like 1976’s Grammy-winning Mark Twang, a showcase for his banjo frailing, fiddling, and flatfoot dancing.

As that album and its river-theme songs indicated, Hartford was by then as interested in riverboats and steamboats as music. His fourth-grade teacher had an abandoned steamboat installed in the schoolyard, and the sight fascinated Hartford. As a teen, he worked on towboats and was a night watchman on the famed Delta Queen steamboat.

Music had distracted him from his boat love: “I tended not to think about it, the way one would not think of an absent lover,” he said. But by the mid-Seventies he fell in love again and worked as a steersman on another boat, the Julia Belle Swain; later, he applied for and received a license to be a riverboat captain on the Mississippi, Ohio, and Cumberland Rivers. As he told a reporter a few years before his death, “I’m a riverman first, a musician second, to support my steamboat habit.”

He was also supported by the steady income provided by “Gentle on My Mind.” When BMI announced its list of the most played songs on radio and TV in the 20th century, “Gentle on My Mind” came in 16th, in between the Police’s “Every Breath You Take” and the Beatles’ “Something.” No one was more surprised than Hartford. “He always said, ‘There’s no chorus, there’s banjo and everyone said it would never fly,’” says McCoury. “But that song enabled him to lead the life he wanted to live. It let him do whatever he wanted to do.”

For his part, Hartford preferred versions by Campbell, Roger Miller, and Elvis Presley over Frank Sinatra’s. In later years, Hartford kept a framed copy of a bad review of Sinatra’s schlocky cover in his house. “The guy who reviewed it just slammed it,” McCoury recalls. “John loved that.”

Well into the Nineties, Hartford became a walking, talking embodiment of working and surviving outside the mainstream music business. He released quirky bluegrass albums, played festivals, and surrounded himself with both veteran and up-and-coming folk, country, and bluegrass players like McCoury. His house in Madison, Tennessee, overlooked the Cumberland River and was filled with autographed Mark Twain books and photos of old boats; even the wood paneling in his bedroom replicated the type used on riverboats. Always eager to make music, he could be seen walking to the homes of fellow musicians. His fiddle under his arm, he’d occasionally yank an index card out of his front pocket to jot down a lyric or word for a song before jamming the card back in.

In 2000, Hartford again found himself navigating close to the mainstream thanks to his participation in Joel and Ethan Coen’s O Brother, Where Art Thou? When the soundtrack became a left-field sensation, bringing mountain music to the masses, Hartford seemed on the verge of another breakthrough moment. But his health prevented him from fully capitalizing on it. Hartford had first been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1981 and had undergone treatment. But the cancer returned several times and, by 2001, it returned more lethal than ever. “He’d go through treatment and he’d be OK for a while,” says Hogue. “But then a few years later it would come back.”

Hartford would still welcome friends and fellow musicians into his home, but they could tell the cancer was having its impact. “He was still wearing his hat,” says Cash of the bowler that Hartford often sported onstage and on album covers. “He was definitely still in character. But you could tell he didn’t feel well. He didn’t get out of his chair.”

During one of his last jam sessions with local players, McCoury saw the impact of the disease firsthand. “The saddest part is that he couldn’t play,” he recalls. “He couldn’t move his hands. I remember being in a circle, picking with him, or actually picking for him. He’d say, ‘You do this song for me.’ He just wanted to hear music. We all knew it wouldn’t be too long then.”

Despite his aversion to pop and commercial music, everyone who knew Hartford insists he would be amused by this late-period renaissance of his music. But why now? “We’ve been trying to figure that out ourselves,” says Hogue. “Some of that music was written in times of struggle, so we can relate to it on a deeper level. It’s not superficial. It’s not candy-coated. It’s music that speaks to hardship, despair, and loss. It gives solace to what we’re all feeling — to know we’re not alone.”

For her part, Hull has been drawn to another deep track, “Today,” from that debut Looks at Life album. “It’s basically saying, ‘I used to think about all these things in the future, but all that matters is this moment today,’” she says. “You can be so concerned about the things in front of you that you can lose sight of the beauty of the moment. I have to remind myself about that a lot anyway. It’s a beautiful message.”

Popular on Rolling Stone

Source: Read Full Article