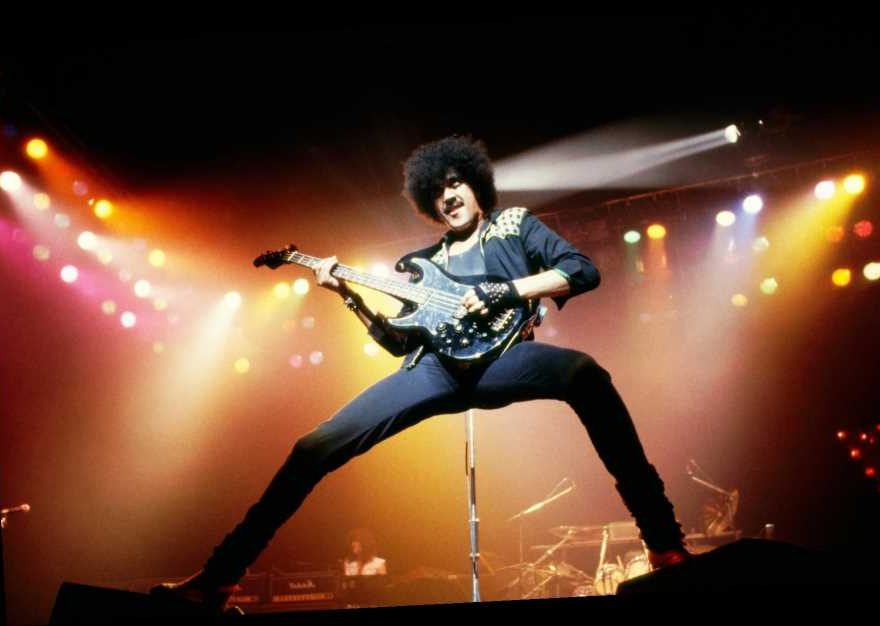

The Irish have put up with a lot of bullshit over the years. There’s England. The Troubles. The kittening of the Celtic Tiger. Enya. It’s not been an easy history. And black people, those living in mostly white countries anyway, they’ve put up with a whole bunch of bullshit, too. So if we pretend there’s an iota of depressing truth being bandied about when, in Roddy Doyle’s novel The Commitments, the irrepressible yet wee bit naïve protagonist Jimmy says that the Irish are the blacks of Europe, then it’s fair to say that Thin Lizzy frontman Phil Lynott, a black Irishman, and that’s black as in race, not dark-haired Gaelic phenotype, well, he probably put up with more bullshit than most. As an outsider among outsiders, he found a way to deal by starting an outrageous, sad-boy weepy, myth-steeped, bad-boy bragging, bulldozing rock band, and fair play to him. Born winners play the worst blues.

20 Insanely Great U2 Songs Only Superfans Know

You know, Sigmund Freud said the Irish are impervious to psychoanalysis. Er, Matt Damon playing Irish-American in The Departed said that Freud said that. As far as anyone can tell, the good doktor never actually uttered those words; the line is just a charming bit of cultural mythmaking malarkey, which makes it very Irish, very rock and roll and totally Phil Lynott. So even if you can’t put the Irish on the couch, you can safely surmise that when people are born beneath the underdog, one way to deal is by learning to spin some yarns, and by developing some swag. That’s what Lynott did, and he wrote Thin Lizzy’s “Róisín Dubh (Black Rose): A Rock Legend” — found on 1979’s similarly-titled album — and it’s the best Irish rock song of all time.

Okay, Thin Lizzy. If you’re a casual music fan you probably know the band’s 1976 single “The Boys Are Back in Town,” taken from the album Jailbreak. That smash hit single and modest hit album, both of which are truly fantastic pieces of roguish hard rock, were Lizzy’s biggest, and pretty much only, noteworthy American successes. They soldiered on as a big U.K./European attraction till 1983 (and a version of the band is still on the road today). In 1986, Lynott, dogged by alcohol and drug addiction, died tragically and early, at 36 years old from pneumonia and heart failure, circumstances that, depending on how much of softy you are, either raised him up or relegated him down to the realm of long-ago legend.

And “the legends of long ago” is where “Black Rose,” a song about songs, a myth about myths, a messily epic, brilliantly exaggerated and melodramatic ode to Ireland by the ur-Irish rock band begins. Lynott tells a tale of kings and queens as guitarists Scott Gorham and Gary Moore riff on a modified Irish slip jig, only with hard rock distortion and road dog bite, backed by drummer Brian Downey bouncing around the compound meter. Then Lynott, who always sounded like he was either bashful or boastful and who here is a bit of both, nods to the folk hero Cuchulain, dark and sullen, who always won, and who promptly dies in the next line of the lyrics. (Because no one does fatalism like the Irish.) The guitars meanwhile are just ripping through dueling licks in Celtic modes, rapiers slicing through the air, and Lynott, a fatalistic street punk with a head gloriously full of cowboy movies, Hendrixian comic book hoo-ha, roving vagabonds and that perfectly sentimental Irish poetry, he taps his temple and turns the key that lets him into the fantasy pub where all those doomed hooligans drink and dance together, which is exactly where “Black Rose” takes place. Once Lynott’s in there, he tells everyone to shut up and listen. “Play me the melodies, so I might know,” he sings. “I want to tell my children oh.”

That’s exactly, beautifully, what Moore and Gorham do next. They play the majestic, eternal, sentimental melodies of “Danny Boy,” “Shenandoah,” “Wild Mountain Thyme” and “The Mason’s Apron,” the last played so fast and hard that you can just about see the sweaty stepdancers slamming their ghillies into the floor, sending up splinters, absolutely lost in this outlandish heavy metal reeling and rolling.

Then that music stops, and misty keyboard chords waft in. Lynott’s voice is echoing now, as if he were singing from the top of the mountains of Mourne, his voice carrying down across the valleys of green heather into the hearts of the children who would cover his songs: U2 and Metallica and Mastodon and the Smashing Pumpkins and Cass McCombs and Def Leppard and Ted Leo and the Replacements and so many others who heard the romance in hard guitars and tender feelings. Gorham and Moore swirl and drone around their singer, sneaking in snippets from “Whiskey in the Jar,” the whole band pulsing with a collective yipping yarragh. Heading home, the rhythm section still jigging, Lynott begins a roll call and, in classic Phil fashion, delivers the names in puns he probably found when they fall off a limerick somewhere:

And it was a joy that Joyce brought to me.

George, he knows Best.

Oscar, he’s going Wilde.

Brendan, where have you Behan?

Synge, playboy of the western world.

Van, he is the man.

And if you don’t want to be Irish by this point in the song, you need another drink. And if, by the grace of God, you are Irish, we owe you another drink.

Ah, but sly Phil frowns and reminds us that “starvation, it’s running wild,” which is a potato famine callback, because life is hard, none of Best, Behan, Synge nor Wilde, let alone the singer, reached old age and it’s a long way from Tipperary. So get your fill, lads and lassies. Sing a song of praise and fight the bullshit with all the blarney you can muster because the fadeout is coming. But before it’s here, raise a glass to telling tall tales, to wild-eyed boys and chicks so cool they’re red-hot, to Cuchulain and getting by with what you got, to Phil Lynott, to Thin Lizzy, to the great emerald green part of your heart and to the dispossessed, the drunk and to this:

This story was originally published on March 17, 2014.

Popular on Rolling Stone

Source: Read Full Article