“Between the World and Me,” Ta-Nehisi Coates’ 2015 New York Times bestselling book — and the 2018 Apollo stage performance of the same name — has been reimagined for the small screen. Directed by award-winning Apollo Theater Executive Producer Kamilah Forbes, this story of aspiration and durability combines elements of the original stage production, including readings from Coates’ book by a bevy of celebrities, and takes on a new urgency against the backdrop of a global pandemic that’s disproportionately affecting Black people, as well as the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and the global protests that followed.

It’s a dynamic visual ode to Coates’ poetic letter to his 15-year-old son, Samori Coates, on coming of age as a Black boy in America; for a Black son who does not yet realize that he will very likely have to walk the same long, hard road in a country that doesn’t love him back, like his father has done. A rude awakening awaits. And for those reasons alone, the film is a kind of heartbreaking.

How do you adapt a book that’s essentially a long, poetically-written missive from a father to his son? There’s maybe really no other way than what director Forbes does here — and she does pull it off. It’s a mix of epistolary non-fiction, memoir, and political thesis, with cinematography by Bradford Young, which of course means the new footage looks good. (It’s just too bad none of it was included in the only trailer HBO cut for it.)

It begins with performance of Coates’ stories of his youth, tracing his path into manhood, his personal trials and triumphs, and his struggle to find his voice as a writer as a vehicle to reflect on what it means to be Black and male in America. Joining him in the conversation are performances by Mahershala Ali, Angela Bassett, Angela Davis, Jharrel Jerome, Ledisi, Janet Mock, Joe Morton, Wendell Pierce, Phylicia Rashad, Kendrick Sampson, Yara Shahidi, Courtney B. Vance, Pauletta Washington, Susan Kelechi Watson, Oprah Winfrey, and others.

They all gathered to tell one man’s story of how his social consciousness evolved, and the impact that had on how he viewed himself.

Like the book, the film is also divided into chapters. And the stories Coates tells about his life on the streets of Baltimore; at Howard University (or, as he refers to it, The Mecca); the police killing of a close friend named Prince Jones, and how he felt when his son was born are vividly told and engrossing.

On his living room couch, and then on his balcony in mostly closeup shots, Jerome subtly elucidates the pains of growing up Black in Baltimore’s inner city; almost prancing through Howard University’s famed campus, Watson (also a producer on the film) ebulliently celebrates HBCUs (Historically Black College and Universities); Ali offers cozy and charming performance of passages on Coates’ various flirtations with women throughout college until he met his future wife, Kenyatta Matthews; the great Rashad in a particularly sublime piece on Coates’ recollection of the September 2000 police killing of her son (and his friend); and on the music front, Tariq “Black Thought” Trotter and Ledisi provide music in a collaboration for the end credits.

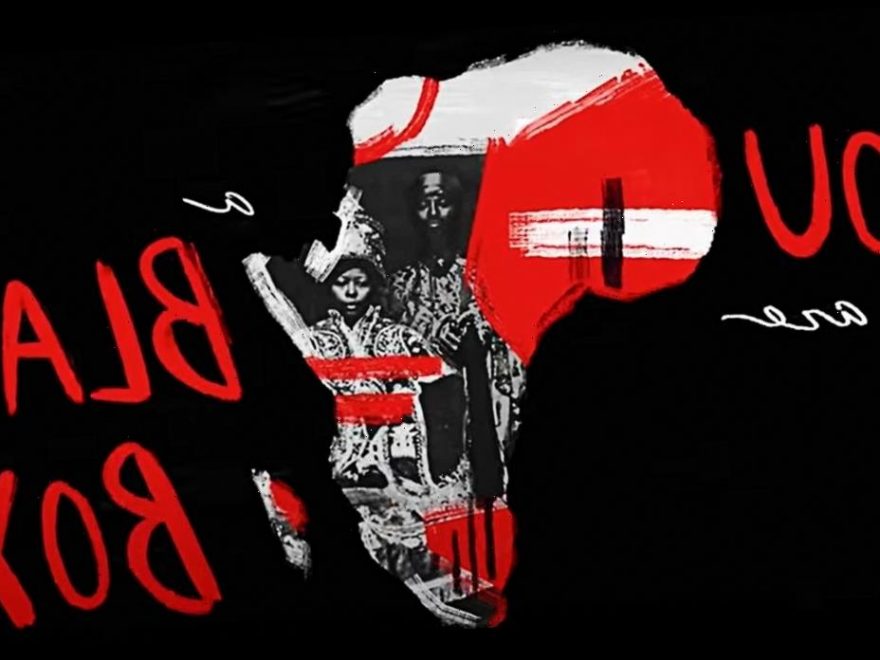

For the film’s visual style, director Forbes seemingly uses every tool in her toolbox, combining powerful performances with elements of the Apollo’s production, which primarily comprised of actors performing passages as a band played in the background.

Forbes also incorporates video montages featuring the joyous faces of the celebrities who performed in the film; think something like the “Black Face” sequence in Terence Nance’s HBO series, “Random Acts of Flyness”; archival footage of activists like Malcolm X and Angela Davis speaking at rallies as well as bloody racial uprisings, photos, paintings, musical performances, on-screen text and animation — all sometimes overlapping each other. It’s all very spirited, even the more solemn scenes.

As the film appears at a moment when the spectacle of Black Americans being killed by police officers is being captured thanks to mobile phones, it creates a screaming call for change. (Some of that ghastly cell phone footage was worked into the film.)

Mostly via Coates’ words, the film is not necessarily optimistic about America, but it’s not necessarily cynical either. It sees where America has fallen short, and continues to fail as a nation, while also pointing out how Black people have always and will continue to survive as a people. And it challenges those who have benefited from the country’s time-honored tradition of systemic racism.

“Between the World and Me” is as layered as the Black experience in America. If you’ve read the book, which is also layered, you should recognize passages from it. But the film brings the book to its own visual life, and does so in a creative, engaging style, speaking to the country’s schizophrenia, and tells the truth about America, because history is often told from records left by the privileged. But even more importantly, it drives home the point that what is primarily and perpetually in danger, the Black body, is also the site of ultimate strength and pride.

It might be tempting to skip the book if you haven’t read it, and just watch the film instead — but the film only contains select passages from the book, and each is an entirely different experience. Do both.

Grade: B+

“Between the World and Me” debuts Saturday, November 21 at 8 p.m. ET/PT, on HBO.

Source: Read Full Article