Adál Maldonado, an influential Puerto Rican photographer and artistic provocateur who explored the psychological and cultural fallout of the Puerto Rican diaspora in New York, died on Dec. 9 in San Juan. He was 72.

His death, in a hospital, was caused by pancreatic cancer, said Francisco Rovira Rullán, his gallerist in San Juan and the manager of his estate. Mr. Maldonado had moved back to Puerto Rico in 2010.

Mr. Maldonado’s primary subject was identity, a concept that for him was constantly shifting depending on his circumstances.

When he was a teenager, he moved with his family from their home in the mountainous Puerto Rican countryside to New Jersey and then to the urban cacophony of the Bronx. The experience left him with a sense of displacement that would be the driving theme of his art and make him a quintessential “Nuyorican” — one who straddles New York and Puerto Rico and feels entirely at home in neither.

“We are multilayered because so many different cultures and races came through Puerto Rico with the slave trade,” he told The New York Times in 2012. “I was raised to feel that I had many different dimensions that I could choose from.”

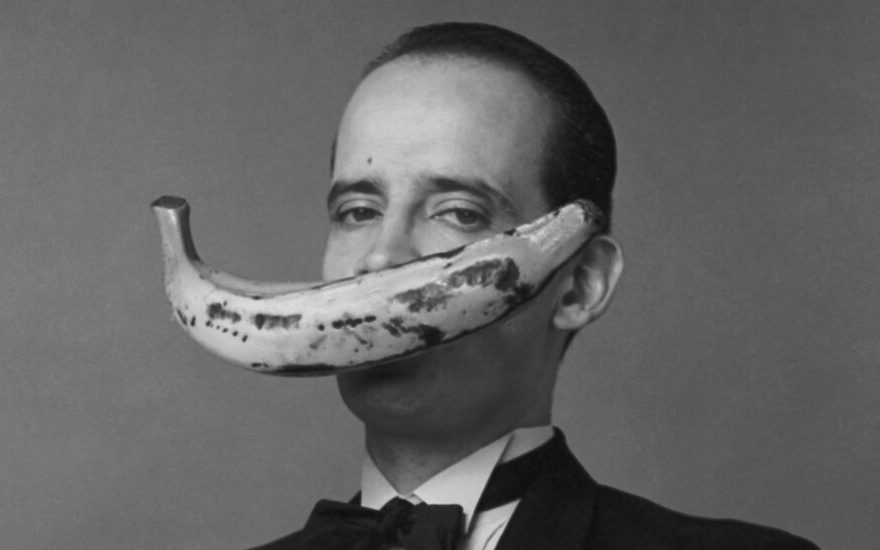

For more than 45 years Mr. Maldonado — who went by just Adál professionally, a moniker suggested to him by the photographer Lisette Model — worked in multiple mediums across various genres. His art was often infused with bitingly satirical humor and a subversive political message.

It has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museo del Barrio in New York as well as at the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; some of his photographs remain in their permanent collections.

His profusion of works include photo novellas — small photo storybooks with words, like “I Was a Schizophrenic Mambo Dancer for the F.B.I.” His “La Mambopera” (2006), a musical play, incorporates elements from film noir and science fiction in portraying a dark future in which Latin music is banned.

Mr. Maldonado used the camera both to document reality and to distort it.

“He consistently played with our expectations around photography, oscillating between questioning and affirming its objectivity, its capacity to capture reality,” said Taina Caragol, curator of Latino art and history at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington.

For his book “Portraits of the Puerto Rican Experience” (1984), Mr. Maldonado photographed 100 prominent Puerto Ricans, including Miriam Colon, Rita Moreno, Jose Ferrer, Marc Anthony and Raul Julia, to document their importance in American cultural history. The New York City public school system used these portraits in its social studies curriculum, and the National Portrait Gallery acquired 15 of them.

Among his best-known endeavors is “El Puerto Rican Embassy,” an elaborate, satirical piece that he created in 1994 in collaboration with the poet Pedro Pietri. Combining poems and pictures, the project imagines a Puerto Rico that has achieved self-determination after being long in limbo as a U.S. commonwealth, neither independent nor a state.

The government in “Embassy” has its own national anthem, written by Mr. Pietri in Spanglish; its own church, La Santa Iglesia de la Madre de los Tomates (The Holy Church of the Mother of the Tomatoes); and its own space program. (In Mr. Maldonado’s telling, American astronauts land on the moon in 1969, only to discover that Puerto Rican explorers had gotten there first.)

Their fictional embassy issued passports with deliberately blurry images in documents that, though realistic-looking, were actually filled with poetry. By blurring the photos, Mr. Maldonado meant to convey the political and psychological ambiguity of Puerto Ricans — American citizens who often feel like colonial subjects.

“Adál spoke about ‘imagination’ as his nation,” Dr. Caragol of the National Portrait Gallery said in a phone interview. “He used that phrase to allude to the endless possibilities of freeing ourselves from oppressive social and political structures by unleashing the imagination.”

Adál Alberto Maldonado was born on Jan. 1, 1948, in Utuado, P.R., where his parents were farmers. After they divorced, Adál and his sister moved with their mother to Trenton, N.J., when he was 13. They lived in an apartment over the studio of a portrait photographer, who taught Adál how to process film and print it, techniques that Adál would pass on to other photographers, including Robert Mapplethorpe.

Adál’s mother remarried, and the family moved to the Bronx when he was 17. He then studied photography at the Art Center College of Design in Southern California and the San Francisco Art Institute, from which he graduated in 1973.

He returned to New York in 1975 and helped start Foto Gallery in SoHo. His first book, “The Evidence of Things Not Seen” (1975), consisted mostly of post-surrealist collage self-portraits along with his portraits of other photographers who had influenced him.

Mr. Maldonado moved back to Puerto Rico a decade ago when his mother, Mari Santiago, who had returned there in the 1960s, became ill. She survives him, along with a son, Lucian, and a sister, Nilsa Maldonado. Mr. Maldonado had never married.

Many years before in New York, he had experimented with a series of photos that he called “Puerto Ricans Underwater,” which he had then put aside. After he resettled in Puerto Rico, being underwater took on new meaning when the island began drowning in $78 billion in debt. The financial crisis became a catastrophe after Hurricane Maria hit in 2017, killing about 3,000 people and leaving much of the island in ruins.

Mr. Maldonado started photographing ordinary people, most of them strangers, whom he had recruited online to come to his home and pose in his bathtub, under water. The results were eerie evocations of Puerto Rico’s sense of drowning and helplessness.

Among the most striking is a man wearing a black T-shirt that says “Muerto Rico,” or “Dead Rico.” The photo won the People’s Choice award as part of a competition at the National Portrait Gallery and became part of Mr. Maldonado’s series “Puerto Ricans Underwater / Los Ahogados (The Drowned),” published in 2017.

“He put a face to a community at a moment when that community was faceless,” Mr. Rullán, his gallerist, said in a phone interview.

Among Mr. Maldonado’s final works was a series on clouds, which he watched from the hospital after his cancer was diagnosed.

“I was looking at clouds from my hospital bed,” he told Smithsonian Magazine in June, “and felt like they were metaphors for transition and the impermanence of things.”

Source: Read Full Article