In 1978, the adversarial New York duo Suicide played a show in Boston, opening for the Cars, local heroes who’d crossed over into pop success. Suicide performed a set of assaultive and static electronic music, and the unhappy audience demonstrated its distaste by throwing ashtrays, some of which hit the singer Alan Vega. But Vega and his bandmate, Martin Rev, had recently finished European tours opening for the Clash and Elvis Costello during which they caused a literal riot in Belgium. (It was later documented on a live recording, “23 Minutes Over Brussels,” named for the length of Suicide’s set before the gendarmes were summoned.)

The day after the Boston gig, a local radio D.J. who’d seen it interviewed Vega and asked how it had gone. “Well, we beat the hell out of them,” Vega replied, laughing happily.

Liz Lamere, Vega’s wife and musical partner for several decades, called the anecdote “a beautiful analogy for Alan’s life.” (Vega died in 2016 at 78.) “People think Alan sang about gloom and doom, all this negative stuff,” she said. “There was always a layer of beauty and hope in everything he did.”

That contrast is an enduring hallmark of “Mutator,” a posthumous Vega album due April 23, which he and Lamere recorded in 1995 and 1996, and she recently produced and mixed with Jared Artaud, a Vega disciple who fronts the minimalist Brooklyn band the Vacant Lots.

It’s the first in a planned series of archival releases, drawn from what the singer called “the Vega vault,” that will be issued by Sacred Bones Records. The vault, a vast catacomb of Vega’s writings, paintings, drawings and music, includes a cassette tape that Artaud calls “the Holy Grail of the archive”: a soundboard recording of Suicide’s September 25, 1971, performance at Lincoln Center.

When Vega and Lamere met in 1985, at a party for his album “Just a Million Dreams,” he was in his 40s and living at the Gramercy Park Hotel, and she was a Wall Street corporate lawyer two decades his junior. “We were both thunderstruck when we first saw each other,” she said during a video call from Florida, where she was visiting her mother, Toots, who briefly wandered into the frame. “Just a Million Dreams” was a tidy, new wave-sounding record helmed by hitmakers, and it was supposed to be Vega’s bid for pop success.

“That was the mantra at his record company: ‘There’s a diamond in the rough here. He could be a rock star,’” Lamere said. The idea turned Vega’s stomach, Lamere said, “because that would take away some of his freedom to, as he said, be the research scientist in the basement.”

At the time, New York’s punk rock era was starting to be documented, but “Suicide was never mentioned,” Lamere said. “And Alan would be like, ‘Do I exist? Did that all really happen?’” She got his song publishing rights in order and persuaded him to produce his own master recordings and then license them to record labels. They also began making music together in the Financial District loft where they lived with their son, Dante, now a 22-year-old hip-hop producer.

The Vega-Lamere partnership wasn’t as unlikely as it might initially sound. Lamere played varsity soccer at Tufts before getting her law degree at Columbia, but she’d already exhibited signs of restlessness: She played drums in rock bands, including Backwards Flying Indians and SSNUB (an acronym for Sgt. Slaughter’s No Underwear Band), which performed at CBGB.

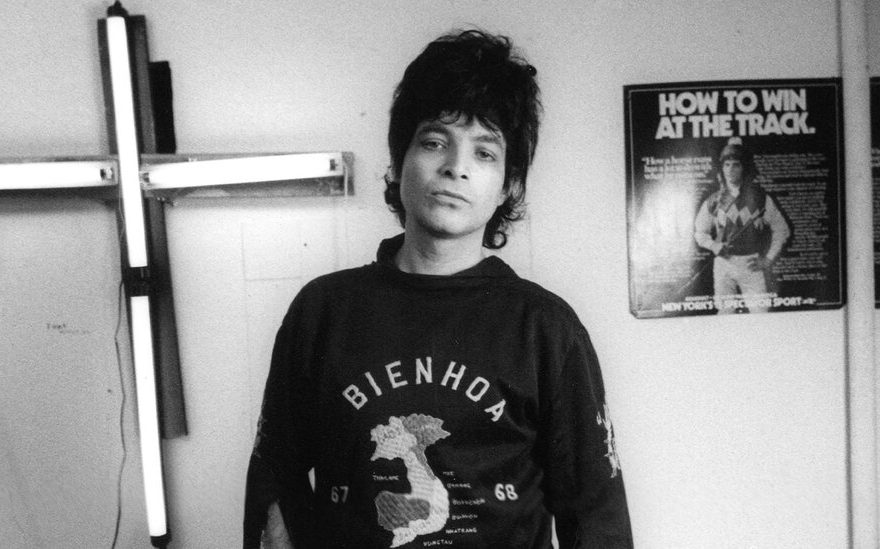

Vega was known (to the extent he was known at all) for brandishing a bicycle chain onstage as a weapon, self-mutilating with broken glass and making music that was corrosively anti-commercial. But the musician born Boruch Alan Bermowitz had a life before Suicide, one that steered him toward art, confrontation, desperation, anxiety and compassion.

Vega’s parents, Louis and Tillie Bermowitz, were Orthodox Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who were able to move from the Lower East Side to Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, thanks to Louis’s job as a diamond setter. Vega went to Brooklyn College where he majored in astrophysics, but got derailed when an art teacher saw him sketching one day and advised him to change course.

At college, he met Mariette Birencwajg, a Holocaust survivor from Belgium, and they married in 1960. She is the author of “Mindele’s Journey,” a 2012 book that memorialized her family, most of whom were killed by the Nazis. In a 2016 blog post, Mariette Bermowitz wrote that the Swiss surrealist painter Kurt Seligmann, who taught Vega, considered him “a prodigy.” Vega also studied with the abstract painter Ad Reinhardt, another significant influence.

To Lamere, this is the context that’s needed to understand her husband: “Alan came out of the Great Depression, post-Holocaust, Jewish immigrant parents. There was always a connection to what was happening to the underdog — the disenfranchised, the disempowered, the oppressed.”

The young Bermowitzes lived a domestic life in Brooklyn. He worked for the welfare department (where he learned about government funding for the arts, which was soon to play a big role in his life) and painted in the evenings. In 1969, Vega saw Iggy Pop and the Stooges at Flushing Meadow Park in Queens, and was inspired to commit himself to a life of ideas and art. “And he made the decision, which was a very difficult one, to leave his married life,” Lamere said. (“My world crashed in,” Mariette wrote on her website.)

Vega moved to Manhattan and helped run Museum: The Project of Living Artists, a Greenwich Village space that was open to performing and visual artists, political activists and anyone else 24 hours a day, thanks to the government funding he had secured. Late one night when he was there experimenting with musical feedback, he met Martin Rev (born Martin Reverby), a jazz keyboardist from Brooklyn. The two formed Suicide, initially with Vega on trumpet and Rev on drums, before they switched to vocals and keyboards.

Vega tried to explain that the band name referred not to any particular suicide, but to the country’s. “America, America is killing its youth,” he howled on “Ghost Rider,” over Rev’s distorted, two-note organ riff. It was music made with an abundance of ideas and audacity, and a lack of money. Rev played a $10 Japanese keyboard, and a few years later added a $30 Rhythm Prince drum machine that spit out chintzy rumba beats.

Gigs were hard to get. Record deals? forget it. By the time Suicide released its first album in late 1977, Vega was 39, making him the senior citizen of downtown punk.

The singer Lydia Lunch, who’d recently moved to New York, wandered into Max’s Kansas City one night and joined the nine other people who’d come to see Suicide. The music “was raw, sexy, psychotic — but there was also a romance to it, with almost a doo-wop quality,” she said in an interview. “But it was Alan’s stare and intensity that was amazing. He was a Method singer — he was in those songs. If he saw you, he was seeing right frickin’ through you.”

“And he and Martin were both really nice, on top of that,” she added.

Artaud, who worked on the vault release, did not meet Vega until after his band covered a Vega song on “Psych Out Christmas,” a 2013 compilation. By then Vega was in what he called “the Tony Bennett phase of my career,” in which he was treated not as a pariah or a freak, but as a revered elder. He showed his light sculptures in prestigious galleries. His music was used in fashion shows by Agnès B. and Dries Van Noten. The Rollins Band covered Suicide’s “Ghost Rider” on the soundtrack to “The Crow,” which sold three million copies, and Bruce Springsteen did a version of “Dream Baby Dream.”

“Suicide’s like the Beatles to me and my band,” Artaud said. He had “a close relationship” with Vega, who lived only one subway stop away. In 2012, Vega had a stroke, which slowed him to a shuffle, and his health continued to decline.

“I think he knew his time wasn’t long,” Artaud said. “He would hint at things like ‘When I’m not here,’ or ‘When I’m gone.’ I felt we were building this kind of pact. The heaviest thing for me was when he said, the last time I saw him, ‘I’m ending. You’re beginning. And I’m passing the torch down to you.’”

The posthumous album “Mutator” exemplifies Vega’s extremist senses of doom and beauty. On “Fist,” Vega croons “Destroy the dominators,” over a bed of swamp-crawling synths and a deadpan hip-hop beat, while on the bucolic ballad “Samurai,” he declaims lyrics that are by turns ominous (“Missing girls/Who’s been killing ’em?”) and impenetrable.

Artaud is helping Lamere catalog and digitize the Vega vault. “It will take some time,” he said. Vega liked to record a bunch of songs, then move on to the next bunch without releasing or mixing the first, which has left a sprawling jumble of his work: “He was always focused on tomorrow.”

Source: Read Full Article