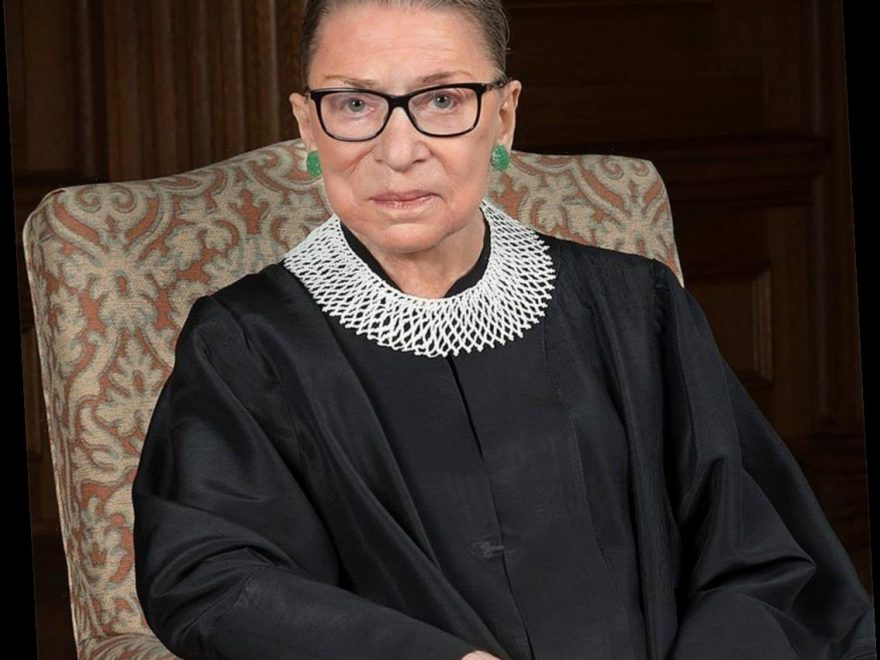

Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg has died at the age of 87, but she leaves behind a huge legacy that changed the course of human rights in America forever.

On Friday, Sept 18, right at the start of the weekend and the Jewish holiday Rosh Hashanah, the world was hit with yet another devastating loss.

It was announced that Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, 87, who had served on the Supreme Court since 1993, had died of complications from pancreatic cancer. The initial impact of her death could immediately be seen on nearly every major social media platform, with reactions ranging from sad to furious, from mourning a beautiful life to fearing what the loss means for the future.

One tweet by author Ruth Franklin quickly began making the rounds.

"According to Jewish tradition, a person who dies on Rosh Hashanah, which began tonight, is a tzaddik, a person of great righteousness," she wrote. "Baruch Dayan HaEmet."

Ruth's death is politically complicated this close to the presidential election (since the president nominates replacement justices), but the loss goes beyond that. She was a trailblazer for women in politics, for women in male-dominated fields, really, for women everywhere. She was an example for everyone, ready to fight no matter what it took—even as she stared down death amid her cancer battle.

Hers is a life worth celebrating and a life worth looking back on as we attempt to honor her legacy as best as any of us can.

Ruth, or RBG as she was often known, was born Joan Ruth Bader on March 15, 1933 in Brooklyn, New York. She adopted her middle name when there was another Joan in her elementary school class. She grew up loving Nancy Drew books. At 13, she acted as the camp rabbi at a Jewish summer camp in New York. In high school, she twirled a baton.

Her mother, Celia, didn't get to go to college since she wasn't the son of the family. This led to her instilling a love of education in her daughter. RBG called her mother "a powerful influence" who was always disappointed in anything other than a perfect report card.

"She wanted me to be independent," Ruth told Gloria Steinem in a conversation with The New York Times. "What she meant was [for me to become] a high school history teacher, because she never dreamed there would be other opportunities."

Trending Stories

Lili Reinhart Shares 'Unpopular Opinion' About Jen Aniston & Brad Pitt

Simply the Best 25 Schitt's Creek Secrets Revealed

Brad Pitt, Jennifer Aniston Virtually Reunite for Celebrity Table Read

Celia didn't live to see what her daughter really would become, as she died one day before 17 year-old Ruth's high school graduation. The future justice did as her mother hoped and continued her education at Cornell University, which she says was "the school for parents who wanted to make sure their girl would find a man."

"Four guys for every woman," she told Steinem. "If you came out without a husband, you were hopeless."

Ruth was, indeed, successful by those standards. She met Martin Ginsburg when she was 17 and they were married just a few days after she graduated with a BA in government in 1954.

She said her father was "very worried" because he wouldn't have been able to support his daughter, but his worries went away as soon as another man could.

"Then I married Marty the month I graduated from college, and it was all fine," she said in the NYT interview. "I could go off to law school. If nobody hired me, I had a man to support me."

And it almost looked like no one would hire her, for a myriad of reasons that feel truly outrageous in 2020. She got demoted from her Social Security job for becoming pregnant in 1955, and after her graduation from Columbia Law School in 1959—she transferred from Harvard when Martin took a job in NYC in 1958—law firms were not exactly welcoming to a young Jewish mother. She was rejected by 12 of them.

"There were many firms who put sign-up sheets that said ‘Men Only," she recalled. "And I had three strikes against me. First, I was Jewish, and the Wall Street firms were just beginning to accept Jews. Then, I was a woman. But the killer was my daughter Jane, who was 4 by then."

It wasn't her first time coming second to the very idea of a man. When she was at Harvard, she was one of nine women in a class of 500. All nine of those women were invited by the dean to explain how they could justify taking a spot at the school from a qualified man.

"I was so embarrassed," she told the NYT of that moment, during which she also spilled a whole ashtray on the floor. "But I gave him the answer he expected: ‘My husband is a second-year law student, and it's important for a woman to understand her husband's work.'"

But did she really think that?

"Of course not!" she recalled to the Times.

In the early ‘60s, while working at Columbia, Ruth went to Sweden to write a book about Swedish civil procedure, and that's where her eyes were really opened.

"Between 20 and 25 percent of the law students in Sweden were women," she remembered. "And there were women on the bench. I went to one proceeding in Stockholm where the presiding judge was eight months pregnant."

But in the U.S., women who cared about gender equality were considered "frivolous." RBG remembered the cause not being taken seriously compared with the other issues of the 1960s.

"The thing that disturbed me was when people would say, ‘What are those women doing? They're just riding the coattails of the civil rights movement,'" she said. Ruth would later be known as the Thurgood Marshall of women's rights.

In 1963, Ruth was made a professor at Rutgers Law School and once told eventual fellow justice Elena Kagan that the university actually told her she would be paid less than her male colleagues because her husband had a "very good job." RBG would go on to fight discrimination just like that and so much worse as she, according to Elena, "changed the face of American anti-discrimination law."

She taught at Rutgers until 1972 before going on to teach at Columbia and Stanford. She was the first woman to be granted tenure at Columbia, she started women's law journals and wrote up sex discrimination cases and helped her female colleagues sue for pay discrimination and pregnancy coverage, slowly paving a new way for women in law and in the workplace. At the same time, she was working for the American Civil Liberties Union, serving as general counsel and on their National Board of Directors up until 1980—work that she said heavily impacted her later tenure on the Supreme Court.

"I conceived of myself in large part as a teacher," she told The New Republic of her time writing legal briefs for the ACLU. "There wasn't a great understanding of gender discrimination. People knew that race discrimination was an odious thing, but there were many who thought that all the gender-based differentials in the law operated benignly in women's favor. So my objective was to take the Court step by step to the realization, in Justice Brennan's words, that the pedestal on which some thought women were standing all too often turned out to be a cage."

By 1980, her life in politics officially began when President Jimmy Carter appointed her to the U.S. Court of Appeals. She would serve there until President Bill Clinton nominated her to the Supreme Court in 1993. That is, with a little encouragement from her husband.

According to the documentary RBG, it was Marty who reached out to his business and law contacts to make sure Ruth's name was in consideration. Obviously, it worked.

"Literally, within 15 minutes I decided I was going to name her," the President says in the film.

She was only the second female justice to ever serve on the Supreme Court, after Sandra Day O'Connor. In the highly regarded role, RBG continued to fight for women's rights at the highest level possible in the country—even as she continued to fight for a spot at the table herself.

In the 2014 New Republic interview, Ruth recalled lawyers mistaking her for Sandra.

"They were accustomed to the idea that there was a woman on the Supreme Court and her name was Justice O'Connor," she said. "Sandra would often correct the attorney, she would say, 'I'm Justice O'Connor, she's Justice Ginsburg.'"

Justice O'Connor retired in 2006, leaving Ruth as the only woman on the court until Sonia Sotomayor was nominated in 2009, followed by Elena Kagan in 2010.

"The worst times were the years I was alone," Ruth, who stood at a mighty 5-foot-1 said. "The image to the public entering the courtroom was eight men, of a certain size, and then this little woman sitting to the side. That was not a good image for the public to see. But now, with three of us on the bench, I am no longer lonely and my colleagues are not shrinking violets."

As much as Ruth appreciated her female colleagues, they appreciated her even more.

"More than any other person, she can take credit for making the law of this country work for women," Justice Kagan told Glamour in 2012 when Ruth was honored with at the magazine's Woman of the Year event. "She is a transformational figure…and for me, an inspiration."

In her acceptance speech for that award, Ruth joked that Supreme Court justice robes were not all that chic—or designed with women in mind. But as she always did, she found a way to make herself stand out.

"Judges' robes are made with men's ties and trouser pockets in mind," she said. "Taking a cue from our colleagues abroad, Justice O'Connor and I broke the plain black monotony by wearing a variety of lace collars, and we also added sewn-in pockets. Not very long ago the only way to distinguish the justices, at least in appearance, was to separate the bearded from the close-shaven. Is it not…a wonderful sign of progress that three women now serve on our supreme court and no one confuses me with Justice Sotomayor or Justice Kagan?"

Ruth's many collars (also known as "jabots") were more than just fashion statements. They spoke volumes all on their own, and she wore them for different reasons—one collar for dissents, one collar for majority opinions. She even had collars she wore when she didn't particularly like somebody.

Ruth's collars are an iconic part of her image, often recreated on apparel and accessories. You don't often see a picture of RBG without her collar, and pictures of RBG are plentiful. She's become both a meme and a powerful symbol of feminism, equality, and justice. It all led to her nickname: Notorious R.B.G. Her law clerks had to tell her who that name was referencing.

"My grandchildren love it," she told The New Republic. "At my advanced age—I'm now an octogenarian—I'm constantly amazed by the number of people who want to take my picture."

They didn't just want to take her picture, either. There are documentaries like 2018's RBG that chronicle her life and career, and Felicity Jones played her in the 2018 movie On the Basis of Sex. Kate McKinnon also regularly played her as a badass dancing justice on Saturday Night Live. She was a bonafide star and an unforgettable American icon.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg lived a long life, fuller than many of us could even dream of. In the NYT interview with Steinem, she had just read Anne-Marie Slaughter's book Unfinished Business, which examined the idea of a woman having it all.

"Who does [have it all]?" she said. "I've had it all in the course of my life, but at different times."

In 2020, Ginsburg's health clearly began to decline. She was battling cancer for the fifth time and hospitalized on multiple occasions throughout the year. But she always returned to her duty as a justice even as she recovered from surgery, working up until the very last minute. She even made her professional wishes clear with her official last words, dictated in a statement to her granddaughter Clara Spera.

"My most fervent wish is that I not be replaced until a new President is installed."

The near future may be a little uncertain without her, but there is a lot of hope. RBG leaves behind a legion of girls, women, and many others who wear her face on their T-shirts and her iconic collar on their earrings, knowing it's because of her that they can dream of any life and any career they want. In fact, if they want to, they can have it all.

Source: Read Full Article