My old job was to brief Julia Gillard, and before her Kevin Rudd, for press conferences. The detailed briefing documents they received always included – the phrase passed down, I think, from Bob Carr’s office – “killer facts”, the statistics needed to respond to questions. Both leaders possessed the skill of being able to read a document once, then recite it verbatim on live TV a few minutes later.

Whether you are a fan or critic of those leaders, I doubt their ability to do so figures heavily in your verdict. Instead, you judge them by what they did. The briefings were, in their own way, important – no doubt they prevented various media disasters. Fundamentally, though, they were defensive. They helped prevent an agenda being derailed – they did not set that agenda.

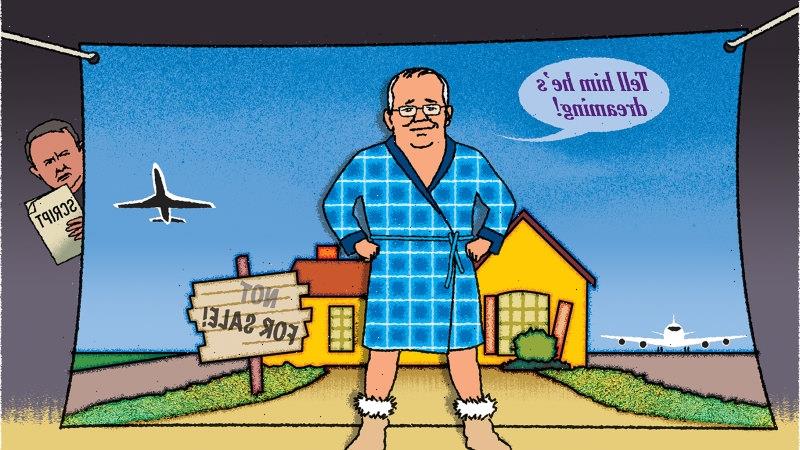

Illustration: Jim PavlidisCredit:

Scott Morrison’s possible defeat means the question of getting things done is an interesting one at present. How will history judge this past decade? Inconsistency might be one aspect – for what threads connect Tony Abbott to Malcolm Turnbull to Morrison? But there is one thread: through those three political terms, very little of lasting significance has been achieved.

If that sounds harsh, remember that Morrison often comes close to articulating this as his aim. He has said he has no interest in legacy. After the last election he said he would do only what had already been promised, which was next to nothing. Abbott and Turnbull achieved little because they failed; Morrison may count his tiny legacy as success. The problems have mounted, are mounting still, but little has been done. Anthony Albanese calls it a “lost decade”, but of course he would say that. Will historians agree?

It was interesting, then, last week, to watch Morrison reframe his prime ministership. This was not for the historians, but for a predictably Morrisonian reason: to enable an attack on Albanese. “Small target”, he said, “means a small leader. A small leader is a weak leader. And a weak leader is a risk to Australia – our economy and our security.”

Morrison then pre-empted the obvious criticism – that he is the smallest target of them all – by saying he was not a small target when he stopped boats, cut taxes, put in place JobKeeper, or created AUKUS. Morrison is entitled to list his achievements but they do not make him, retrospectively, a courageous leader. Half of his short list occurred under other leaders; of the other half, Labor usually agreed, or suggested the change first.

If Morrison was in fact a large-target prime minister, you might expect policy to be at the centre of this campaign. The other interesting intervention, then, came on the weekend, from John Howard. In an interview with James Campbell for The Sunday Telegraph, Howard had sharp words for Albanese – he had never rated him highly, not as a debater or on policy or intellectually. “In modern times,” Howard said, “nobody has gone to an election so policy-light as this bloke.”

But the less predictable part of Howard’s remarks came a few sentences later, when he offered reasons for the rise of the teal independents. One reason, he said, was the lack of policy contests in this campaign. “One of the advantages of having debates about big policy changes is that people take positions on the issues rather than on the general performance,” he said.

Howard didn’t quite say it outright – he is loyal to a fault – but his words raise obvious questions. Whose general performance might voters be casting their harsh judgment on? And who missed the opportunity to kickstart debates about big policy changes?

But why would Morrison care about such critiques now? For much of the campaign he has been hunting for the right frame. Last week, he settled on “strong versus weak”. The reframing of his leadership as “big target” was merely a necessary step towards the more important destination: we are now witnessing a radical reduction of every political issue of the past few years to this strong/weak binary. Perhaps you thought this election was about the climate, or violence against women, or aged care? From now on, for Morrison, it is about who is strong and who is weak.

For Morrison, politically, this makes sense. Morrison is physically large. Albanese has looked nervous at times. This is the simplistic way political framing works. But what about the rest of us – is strong v weak a reasonable way to view this election? What do those categories mean? Was Morrison strong when he failed to deliver industrial relations reform? When he blamed Labor for his failure to legislate an anti-corruption commission? And when has Morrison ever shown sufficient strength to fight for something difficult?

Such rhetoric might not matter so much if it did not migrate so easily to the press. “How are you going to stand up to Xi Jinping if you can’t stand up to us?” a journalist asked Anthony Albanese last week. But what, precisely, would “standing up to” the press look like? And does it bear comparison with whatever “standing up to” the leader of China might look like? I suppose it might, if both involve – as they have under Morrison – simply presenting an aggressive front at press conferences.

Well, then, let’s look at the results. Has Morrison’s approach to the press been good for accountability or governance? Was his “strong” rhetoric about China always useful? “Strong” is perhaps less straightforwardly good than it first seems.

The limitation of the briefings given to prime ministers is that all they do, all they can do, is provide answers – whereas the real job of any serious politician is to shift the questions that a nation asks itself.

Albanese is clearly not a good campaigner. He is not great at answers. But does this quiz show tell us much? Whether Albanese can shift the questions Australia asks itself remains unclear; we will only know if he wins.

The pity of Morrison’s prime ministership is that we know the answer: he can because he does it brilliantly during campaigns. It is how he won in 2019 – “can you afford Bill Shorten?” – and it is how he might yet win again. But a true leader can do it between campaigns, too, bringing the country with him as he embarks upon great and necessary change. Morrison has never yet expressed a desire to do so.

If Morrison wins, and continues to do little, will we continue to think of him as strong, won over by his ability to answer questions – or, at least, respond to them – in a loud voice?

Cut through the noise of the federal election campaign with news, views and expert analysis from Jacqueline Maley. Sign up to our Australia Votes 2022 newsletter here.

Most Viewed in Politics

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article