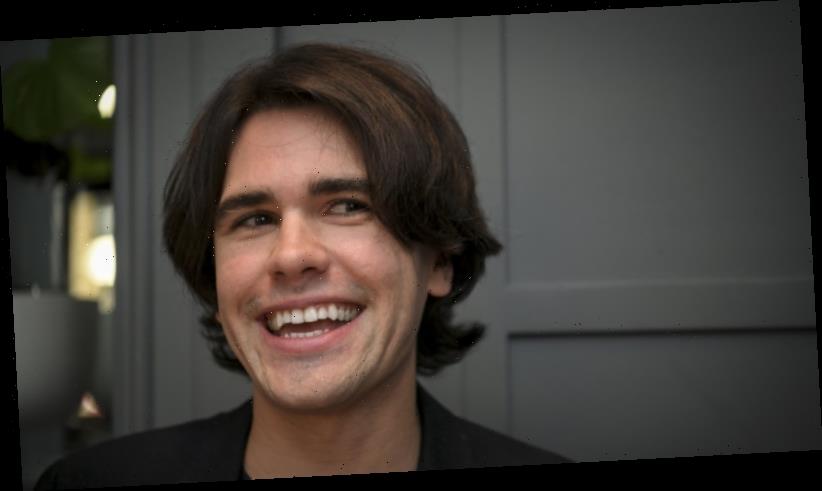

Scott Silven doesn’t do magic, but he does do charm. Given his mop of dark hair, wide smile and engaging manner, it’s easy to see why his intimate dinner-party show At The Illusionist’s Table sells out wherever it plays despite the hefty price tag (each of the 24 guests at the Melbourne International Arts Festival iteration of the show pays $399 for a three-course meal with wine and whisky tastings; the 18 shows sold out in 48 hours).

The 30-year-old – born and raised in Glasgow, a graduate of theatre studies at Edinburgh University and now happily ensconced in Manhattan’s Tribeca district – calls himself a mentalist. “It’s theatre of the mind, which I think of as the purest form of magic,” he says of his craft. “There’s no people in boxes being sawn in half, no strange-looking boxes of props, it’s really just a connection between one person and another.”

“There’s no people in boxes being sawn in half, no strange-looking boxes of props, it’s really just a connection between one person and another," says Scott Silven.Credit:Eddie Jim

At his shows, he insists, the audience does most of the work; he’s just there to facilitate it. “Empathy is key,” he says. “Both of us unconsciously navigating the journey knowing we’re happy with where the path is going to take us. It comes down to empathy and vulnerability and the power of connection.”

You could write that off as sleight of mouth but there’s no question his kind of art works best when the audience willingly goes along for the ride. “I’ve never been heckled but I have had people on stage who really shouldn’t have been,” he says, adding that he never uses plants but sometimes wishes he could control who gets pulled out of the audience at his larger theatre shows. “It’s the worst thing. You really want people who are in that moment, who are connected.”

Calamari, a new horizon for Silven.Credit:Eddie Jim

We’re lunching at Lello, a superb Italian restaurant on the corner of Flinders Lane and Russell Street, where they make their own pasta and celebrate that idea of connection in a different context. And Silven is very much in the moment, happily giving himself over to the chef’s selection, a $59 guided tour through the lunch menu that leaves us in need of elastic waistbands and absolutely nothing else at the end.

He has a thing about seafood – not that he’s allergic, just that he’s a bit freaked out – and he’s trying to get over it, so the calamari is both challenge and triumph. “It’s great,” he says. “I really like the flavour of it.” He even tries a tentacle although he shies away from the big cluster of them, their suction pads visible. “That’s a bit too real.”

Am I open to the moment, I wonder? He has a simple test, which he performs on me at the table – no props, no assistants, no saw; just words, delivered in that soft lilting voice.

“I’m not going to hypnotise you, don’t worry,” he says. “Clasp your hands together, extend your two index fingers [without bringing them together].” I do.

“Your conscious mind is going to tell you those two fingers will not touch, but I want your sub-conscious mind to take over,” he says and my conscious mind is struggling, ever so slightly, to resist. Or at least that’s what I imagine is happening.

“Stare at that space in between your two index fingers and as you stare at that space, like two magnets those two fingers will keep moving closer and closer and closer together,” he soothingly drones.

“And the more you try to resist, like magnets, those two fingers keep moving closer and closer and closer together, and those fingers, like magnets, almost just want to touch.”

And, of course, they do. Like magnets.

We both laugh in delight.

“That shows you’re a really susceptible person, which is great.”

Is it though?

“I think imaginative people are the most susceptible because they have that ability for openness,” he says. I am simultaneously flattered – he thinks I’m imaginative – and sceptical – he’s just saying that because I’m a patsy.

Can you do it to yourself?

“I’ve never been able to hypnotise myself, unfortunately, which would be great. But I do meditation, which is really important for creativity.”

Angel-hair pasta croquette with pumpkin and emmental cheese rests on a moat of buffalo milk.Credit:Eddie Jim

Silven calls the component parts of his act “effects”. But his career began with that old magicians’ staple, a trick. He was four or five years old when his grandfather showed it to him “and I was hooked”.

“He took a little piece of candy and had me write my name on it, and then he vanished it. On the table in front of us was a matchbox wrapped in hundreds of elastic bands. He gave it to me, I took the bands off and then inside was a piece of candy with my name on it. It was wild. And I was just obsessed from that point.”

His grandfather taught him how the trick was done, and it was a watershed moment in so many ways. “Like most traditional magic it was quite disappointing,” he says. “The revelation that magic might not be real was pretty heartbreaking because then you realise that Santa might not be real, the Tooth Fairy isn’t real. It’s a pretty bad existential crisis to have at five years old.”

Recapturing that pre-Lapsarian sense of childlike wonder at the impossible is the key to his act, he says. And learning how to do it has been a lifelong project.

Silven's greatest act of misdirectioin came at 15, when he went to Milan after telling his mother he was going to London.Credit:Eddie Jim

His grandfather also taught him how to cheat at cards. At 11, he discovered a book on hypnosis in his local library; in the back of it a name was written, and that name led him to a magic shop in Glasgow and a man who had developed effects for David Blaine. At 15, he told his mother he was going to see a friend in London during the school holidays but actually he was sneaking off to Milan to do a five-day hypnosis course. Misdirection, you might call it.

“It wasn’t until I started doing media interviews when I was about 25 that my mother discovered what had happened,” he tells me as we devour the cacio e pepe made with burnt-wheat flour, a sensational house specialty. “She was furious.”

Edinburgh uni gave him the theatrical know-how to develop a fully fledged stage show; his studies in psychology, hypnotism and magic gave him the “opportunity to create more interesting theatre experiences”.

His influences weren’t other magicians so much – though the 93-year-old English mentalist David Berglas looms large – as they were filmmakers such as Alfred Hitchcock and David Lynch. “It was the way those stories were told – the signifiers, the metaphors, the hidden messages. That was really how I began to craft my effects, not by looking at other performers.”

Receipt from Lello Pasta Bar for lunch with Scott Silven.Credit:Karl Quinn

He’s far too urbane to ever blurt out, Gob Bluth (Arrested Development)-style, that what he does “isn’t magic, it’s an illusion”, but still, Silven has chosen a very deliberate path that privileges storytelling over spectacle.

“I never allowed myself to go down the easy route of making money doing corporate work or weddings,” he says of his early days. “I wrestled with it, definitely, especially at university where you’re surviving on a tiny amount of money every week. I had friends who did it. Some people do it exquisitely and it’s a beautiful art form, but it just didn’t interest me.

“Every magic show I saw when I was younger was taking something profound and trivialising it. I wanted to attach an honest narrative to it.”

He does big theatre shows too – his Wonder is at the Spiegeltent for six weekend shows during the festival – but the intimate shows are something special. “Each audience brings its own quirks and reactions,” Silven says. “You can’t dial it in. It’s like a new show every night.”

He no longer dines with his guests – he used to, but 14 three-course meals a week began to take its toll – but he relishes the challenge of riding the rise and fall of energy in the room that comes with his departure and return between courses, and the buzz it generates. “There’s a nice sort of Agatha Christie paranoia – ‘did you see this? Did you see that?’”

Do you eavesdrop? “Not at all, and I don’t want to. It could be like a bad therapy session.”

Not that he seems to have too many issues right now. He loves being based in New York but getting to travel, to meet new people and have new experiences. He’s single but comfortable, for now, with that.

Do you ever pull at the dinner parties?

“No,” he laughs. “We’re in a very different climate now. It’s very common that after the show you’ll have Instagram messages, ‘Oh, I’d love to show you around the city’. Best not, just to be safe.”

It could be a bit like “and for my next trick, I’ll make my career disappear!”

“Exactly,” he says. “My management are very careful about that as well.”

He’s done guest spots on American television but he’s not yet a household name over there. “I’ve never been on the fast track to fame or exposure. Every year America’s Got Talent gets in touch to say come on the show, but I just don’t feel it would be right for the stuff I do.”

He knows he could make more money by just doing his big show every night “but how much more do you really need?”

“You’re living a comfortable life, you’re based in New York, you’re travelling the world constantly and getting to do what you love – and you’ve not sold your soul.”

Aye, as they say in Glasgow. That’s the trick.

Scott Silven is at the Melbourne International Arts Festival October 3-20. At The Illusionist's Table is sold out. Tickets for Wonder at the Spiegeltent are available at festival.melbourne/2019

Follow the author on Facebook at karlquinnjournalist and on twitter @karlkwin

Source: Read Full Article