Callin and Brendan Paulhus are driving toward an inferno. It’s mid-September 2020; Los Angeles County has 474 new reported cases of COVID-19, the city is experiencing some of the worst air quality and pollution in the world, and five million acres across the West Coast are scorched due to forest fires. The Paulhus brothers knew all this, and still decided to pack up Bren’s 2016 Toyota Sonata on a Monday, put money down on a four-month lease, and make the cross-country drive from their family’s home in Massachusetts. They have 29 hours left until their destination.

Callin and Brendan Paulhus are driving toward an inferno. It’s mid-September 2020; Los Angeles County has 474 new reported cases of COVID-19, the city is experiencing some of the worst air quality and pollution in the world, and five million acres across the West Coast are scorched due to forest fires. The Paulhus brothers knew all this, and still decided to pack up Bren’s 2016 Toyota Sonata on a Monday, put money down on a four-month lease, and make the cross-country drive from their family’s home in Massachusetts. They have 29 hours left until their destination.

“Nothing could stop us,” Bren says from behind the wheel of the car before laughing. “We said, ‘Fuck everything.’ Even if there’s corona, even if everything is burning, we’re not stopping.”

From the beginning, the road trip has been a fraught experience. The brothers were supposed to leave on a Monday at 8 a.m., but the Toyota needed to clear inspection. When they told the man at the DMV they were headed to California, he informed them that the car wouldn’t make the trip without three new tires. It wasn’t until 5 p.m. that they finally hit the road, and from there the duo’s sense of time has warped.

“There was a period of time where we thought, because we didn’t look at the map, ‘We got to be halfway there,’” Bren says. “We’ve been trucking, and then we look at the map: we’ve made it one state over.”

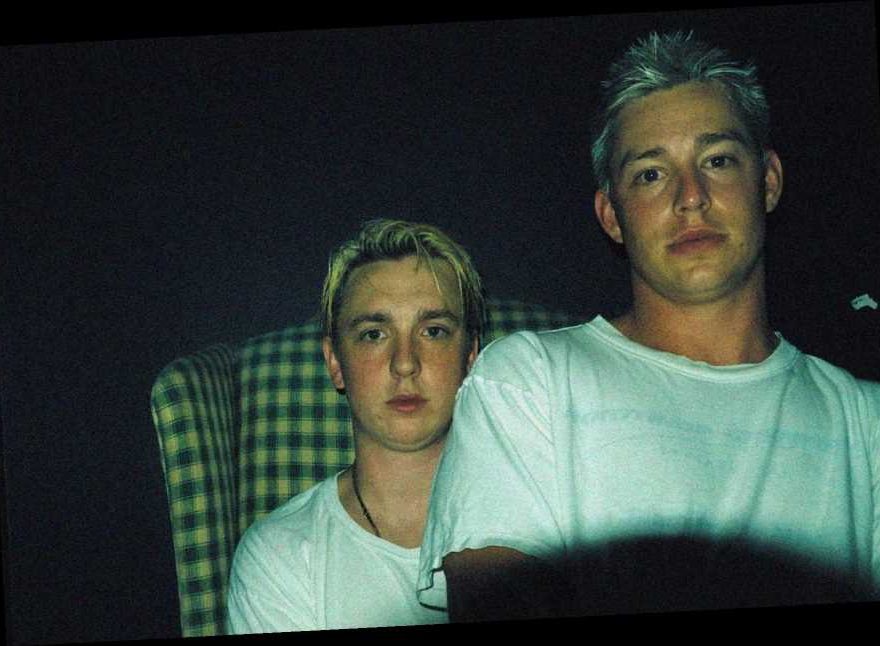

Brevin Kim began in 2015, taking their group moniker from a fusion of Brendan’s name and those of their parents (Kevin and Kim). Bren, 28, is a jovial and gawky presence, while Cal, 26, has a world-weary charm. Despite growing up in a New England suburb, their music is distinctly not of their region: They live in a world of sonic excess built on distortion, reverb, and Auto-Tune. Brevin Kim’s approach to music is the equivalent of highlighting every word in a textbook, while drawing in every spare margin. Their lyrics bounce from self-deprecating (“Mute me, shoot me down, oh, please, I beg you”) one moment to emo atheism the next (“I don’t believe there’s a God/He doesn’t know what I want”).

Only a few weeks prior to their California road trip, Bren was unemployed in a Boston suburb, while Cal was in Florida editing video for a life coaching company, and both of them seemed stuck. During an August afternoon, Cal looked for a serviceable internet connection in a nondescript backyard, while Bren hunkered down in his car. They were (and still are) weeks away from the release of a new album, no less than three, that could make a big difference in their career. In a time when the touring industry has been decimated, independent venues have shuttered, and established stars are battling for real estate with one-hit TikTok wonders, the stakes are evident. Brevin Kim are musicians, not celebrities; part-time workers, not full-time artists. To close that gap, they’re willing to be as flexible as they need to be.

Only a few weeks prior to their California road trip, Bren was unemployed in a Boston suburb, while Cal was in Florida editing video for a life coaching company, and both of them seemed stuck. During an August afternoon, Cal looked for a serviceable internet connection in a nondescript backyard, while Bren hunkered down in his car. They were (and still are) weeks away from the release of a new album, no less than three, that could make a big difference in their career. In a time when the touring industry has been decimated, independent venues have shuttered, and established stars are battling for real estate with one-hit TikTok wonders, the stakes are evident. Brevin Kim are musicians, not celebrities; part-time workers, not full-time artists. To close that gap, they’re willing to be as flexible as they need to be.

That’s one reason why you can classify their music however you’d like. “I definitely do not want to be [part of] a genre,” Cal admits, before laughing. “You can call us whatever you want. We don’t care.”

Similarly, while the brothers frown on social-media virality, they admit that it isn’t completely out of the realm of possibility. “Cal and I are not going to dance and do a TikTok video,” Bren says at first. “That shit’s just not going to happen.” Cal qualifies this statement moments later: “You might end up seeing us on TikTok. Don’t completely rule it out.”

In a financially precarious time for working-class musicians, Brevin Kim are happy to be whoever you need them to be, if it makes their chosen career path a little more viable. “I just want to be able to live off music and do it full-time,” Bren says.

For everything they want to achieve — critical acclaim, widespread influence, a stable income — there’s a list of things they’re openly against. Despite having the type of bleach-blonde hair reminiscent of your typical high-school wrestler, they’re not keen on the Boston bros aesthetic, or even the possibility of trying to launch a sustainable career from their home state.

“I needed to move out of this small town and make a move with life. I feel like it was the best decision for our career too,” Bren says on the way to L.A. “I was stuck in a rut.”

“Every time we’re in L.A., things seem to click, and I was sick of putting it off,” Cal says next. “I just went through a break-up, and I’m dying for change. I was losing motivation and not inspired in my hometown.”

Even being associated with their closest artistic forebear, 100 Gecs, and the genre signifier “hyperpop” elicits complicated emotions. Dylan Brady, one half of 100 Gecs, produced Brevin Kim’s “the wedding” and “Ice Cream Truck,” along with a handful of other songs, and the brothers speak of his production acumen with awe.

“Seeing [100 gec’s] success is reassuring to us, because it shows us that you really can do anything,” Bren says. “If you listen to that — as good as it is and how genius that is — you wouldn’t think that would be popular, but it’s like the most popular music right now.”

Even so, he adds, “I don’t want to totally be that genre personally. But I like having that style sprinkled into our overall style.”

Brevin Kim also seem mystified by the social-media savvy it takes to inspire memes, hate tweets, and YouTube reaction videos; if there is a code to virality, they’re not sure they want to learn it, let alone break it. “I’ll admit sometimes I look at shit and I’m like, not bitter, but I’m like, ‘What can I do to do that?’” Cal says. “But I think if we wanted to do it, we would have at least tried to do it by now.”

This attitude puts the groups at odds with much of the modern music industry. “In the past, I always had this idea that there were music people in the world who just had great instincts,” says Jacob Moore, who signed Brevin Kim to his label, No Matter Records. “I’ve realized now [that] everyone is looking at the same data. Everyone is chasing the same artists based off of viral moments or social media growth.”

Moore made his name in a very different music industry. In 2008, he founded Pigeons & Planes, a blog that became a discovery hub for fans and A&Rs. The site tipped many to Post Malone before “White Iverson” became a phenomenon, and typically posted artists long before the major labels cared. Moore decided to launch No Matter Records in a distribution partnership with Republic Records, so he could sign the very artists he was investing in before the industry got there.

When Moore found Brevin Kim in the fall of 2018, there was little data to sift through. After fielding a request for new music on Twitter and seeing the group’s name, he spent the weekend digging through their music. A couple of days later, Brevin Kim’s former manager DM’d Moore the group’s album Happy Tears in a serendipitous moment. Two years later, Cal and Bren don’t tend to speak of Moore like their label boss. When asked why they decided to sign with him, the answer is simple: “How much he believed in us.”

“‘Cause no one really did, other than a small group of people and our manager at the time,” Bren continues.

“We were also so foreign to attention from the industry. It was like, ‘A record deal?’ We just lit up,” Cal adds. “It wasn’t like there was a bidding war going on then. There might be after this album, but at that time, that was the only offer we really had. Luckily, we also connected deeply with Jacob.”

Moore’s Brevin Kim gamble is partially a bet on his philosophy: If they succeed alongside labelmates like David Wolves (similarly obsessed with dramatic, glitchy, and emotional screeds) and Jelani Aryeh (a purveyor of soothing and celestial-sounding songs), it proves his belief that art can win over data.

“I hate the attitude of, basically, just latching on to things that are already successful,” Moore says. “It should be the label’s job to start that momentum, and not just hop on when something is already moving.”

Brevin Kim made their first album for No Matter in less than ideal circumstances: over 3:00 a.m. FaceTime and Zoom calls, the brothers traded files back and forth from Florida to Massachusetts. Despite the logistical complications, they say the process inspired some of no less than three’s best songs. The album begins with melodramatic howls and a voice that’s been reversed and digitized into a squeal on “shakemedown.” From there, the crunch and anxiety intensifies on “!holyshitohmygod!” and never relents. No less than three runs the gamut between heartbreak and existential angst, but never strays from its relentless need to be catchy. The hooks on songs like “Like This!” and “car” could just as easily been written at a Justin Bieber or Post Malone writing camp.

Part of the L.A. move is meant to get Brevin Kim into some of those rooms where they can write and produce for others. “We just started getting into that world,” Cal says. “We’ve been doing these Zoom writing sessions with a couple people.” He mentions Graham Edwards, who co-wrote 2000s hits including Avril Lavigne’s “Sk8er Boi” and “Complicated” as part of the songwriting and production team The Matrix: “This guy’s, like, a legend. Since then, I feel like we’re opening that door, so we’re setting up some more writing sessions in person in L.A.”

Only a few years prior, Cal was in a PPG Paints six-month training program, on his way toward taking over a paint store of his own; a few months ago, Bren was delivering pizzas during a pandemic. Cal muses that in 2019, they barely had a song that clocked in at more than 20,000 streams on Spotify, and now they have more than one (“somebody, some body,” “Real Friend Best Friend”) sitting at 700,000 to 1 million plays.

“In music, you set these goals, and you have these desires, and then you reach them. I wish it wasn’t this way, because you then feel numb to it once you actually achieve it — but a million streams has been a goal for years,” Cal says. “When we got there, it was a proud moment. I had to step back and tell myself, ‘You’ve been working for this and wanting this for years now.’ But in reality, you just always want more.”

For years, Brevin Kim watched other artists navigate the industry; to them, millions of streams meant millions of dollars. Driving across the country, they seem to be operating on a high that eluded them in Massachusetts and Florida. In a time when so much of the music industry has evaporated — tours, festivals, meet-and-greets — the brothers seem like they have regained a modicum of control by driving to a more promising geographical locale.

“The scariest thing in the world to me, is one day I’m back making pizza,” Bren admitted before this trip began. But even if Brevin Kim are far from comfortable, they’ve found a kind of comfort.

“I just didn’t understand how it worked until we became serious musicians,” Cal says. “It’s just a grind. I was very surprised, but it’s also humbling. It’s nice to know that we’re all just grinding it out.”

Source: Read Full Article