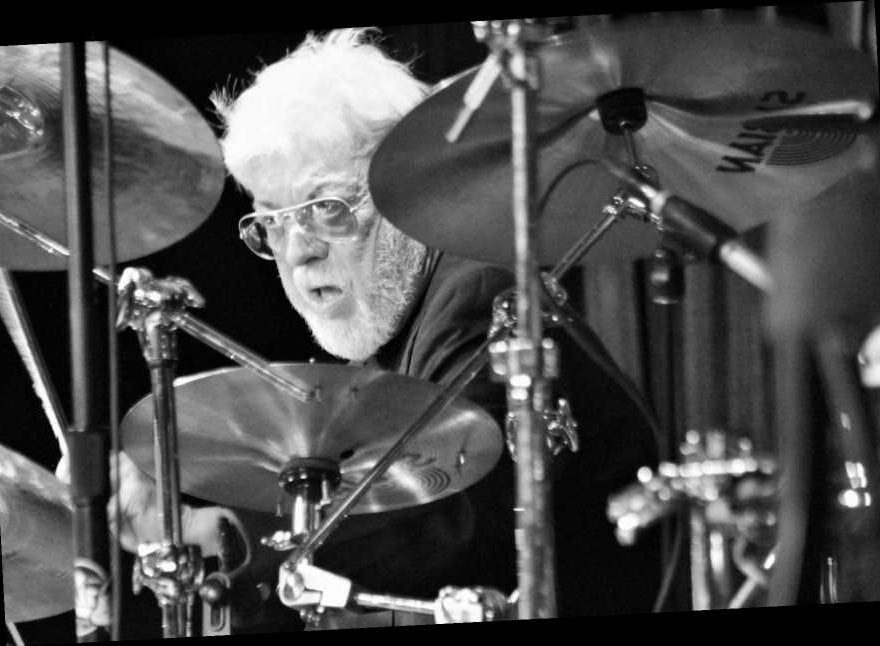

Rolling Stone interview series Unknown Legends features long-form conversations between senior writer Andy Greene and veteran musicians who have toured and recorded alongside icons for years, if not decades. All are renowned in the business, but some are less well known to the general public. Here, these artists tell their complete stories, giving an up-close look at life on music’s A list. This edition features drummer Karl Himmel.

Rolling Stone interview series Unknown Legends features long-form conversations between senior writer Andy Greene and veteran musicians who have toured and recorded alongside icons for years, if not decades. All are renowned in the business, but some are less well known to the general public. Here, these artists tell their complete stories, giving an up-close look at life on music’s A list. This edition features drummer Karl Himmel.

On November 12th, 1977, Neil Young celebrated his 32nd birthday by playing an enormous outdoor festival in Miami, Florida, to raise funds for the National Hemophilia Foundation. “Young and his newly-formed band were crowd pleasers,” read a report in a local newspaper, “performing a mixture of hard rock, country rock, and easy mellow numbers.”

Related Stories

'It Rescued Our Entire Plan Overnight.' How Joe Biden Will Help Rockers Retire

Neil Young Releases 1971 'Young Shakespeare' Live Album

Related Stories

The 30 Greatest Rock & Roll Movie Moments

The Beatles in India: 16 Things You Didn't Know

A key part of that “newly-formed band” was Nashville-based drummer Karl T. Himmel. He first teamed up with Young during the Homegrown sessions in 1974, but this was his first time playing with him in front of a live audience. They didn’t rehearse much, but he’d spent the past decade-plus touring and recording with everyone from J.J. Cale and the Doobie Brothers to Bob Dylan, Elvis Presley, Brenda Lee, Dr. John, George Jones, and Leon Russell, so he was ready for anything that Young threw at him, even a snippet of “Sweet Home Alabama” to honor Lynyrd Skynyrd a few weeks after their tragic plane crash.

The show didn’t do much for the National Hemophilia Foundation since it wound up losing money despite attracting 125,000 fans (“I’m sorry for the kids we tried to help,” one of the organizers told a newspaper. “If we do it again next year, we may have to charge an admission fee”), but it established Himmel as one of Young’s go-to live drummers for the next 30 years. He also recorded with him on American Stars ‘n Bars, Comes a Time, Rust Never Sleeps, Everybody’s Rockin’, Old Ways, and Prairie Wind.

We phoned up Himmel to hear about his epic life in the music world, with and without Neil Young.

Where do you live these days?

I live in Diamondhead, Mississippi. It’s 60 miles from New Orleans, about 80 miles to Mobile, Alabama. It’s real nice. When I want to go out to New Orleans, the ride is nothing and there’s good roads here. I drive a fast BMW and it’s no problem.

Nice. So, how has your Covid year gone?

My wife doesn’t let me go anywhere. We’ve just been staying at home. I’m 75 and I still smoke cigarettes. She doesn’t want me in grocery stores and I don’t blame her. I’ve been really good at doing everything right.

I actually got my shot on Saturday. It’s the one and done, Johnson and Johnson. It was right here in Diamondhead. It took a while to get to that point. It was like, “You gotta go to Biloxi to the Civic Center.” When I got there and looked at the amount of people that were in their car in line, I thought, “Nah, I don’t want to do that today.” It just got to where it never happened. But we’re good to go now, or as good as we can be, if we believe what they’re saying.

I want to go back and talk about your life. What’s the first music you remember hearing as a kid that really connected with you?

It was Dixieland. I lived in Houma, Louisiana. My grandfather had a big, old Southern house that he inherited. I was raised there with my grandfather, grandmother, and mom and dad and aunt. They all lived there. My grandmother played the piano all the time, and she was good. It was a ragtime kind of piano.

As a kid, I was always beating on things with two knives. The next thing I knew, I got me a set of drums and I started watching drummers. My mom sang with a big band every once in a while, and I liked the drums.

How old were you when you started to play?

I’m sure I was at least five or six, maybe seven, real young. I would come home from school and the set of drums was right there by the piano. I was so little when I started, I didn’t sit down. I stood up and played. I finally got a seat and was like, “This is different.” And then I got a hi-hat and it was a real set of drums.

When I was young, I worked with Mac Rebennack, Dr. John. Before he could even drive, my mother would pick him up and take us to gigs together.

How did you meet him?

Through some other people when I was skipping school and hanging out on Bourbon Street because all the music was there. I heard about Mac and he was doing a lot of sessions. We did some sessions together, but mainly we had a gig on Bourbon Street for a long time. It was Mac Rebennack, [pianist] Ronnie Barron, and I can’t remember the name of the bass player.

What year is this?

I was 16, so around 1963.

To go back a bit, who were some of your musical heroes as a kid?

I liked jazz. I was into the Jazz Crusaders and J.J. Johnson. Their records had some of the great drummers on them. I liked old jazz. And of course, I liked Dixieland. When I was growing up, my mom would take me to the Famous Door, which is on Bourbon Street. It was a Dixieland place at the time. I’d go in and sit in and play with the Dixieland band. One of the drummers there, every time he’d see me with my mom he’d be like, “Come here and sit in,” because he wanted to get a drink or something.

It got into my blood from that. When I was younger, I was always playing with older musicians They were the better players because they were older. They taught me what was going on in their lives, music-wise. I was running around with a crowd that was 10 years older than me and they had a lot of knowledge.

I’d hear a record and be like, “Who is that?” They’d be like, “Well, Mac is playing piano. And that’s John Boudreaux on drums.” I went, “Jeez! I want to meet him.” There was really great, local talent. It was exciting.

When Mac and I played, right across the street was Al Hirt’s Club. He had a stage that would turn around while they played. I remember [pianist] Ronnie DuPont saying, “I don’t like that stage.” He didn’t like going in circles. He said he’d look at a girl in the audience and he’d lose her. [Laughs.]

Did you know Fats Domino?

Oh, yeah. And Bobby Charles Guidry. He wrote “Walking to New Orleans.” I was working with him and doing demos. I did an album with him and he was real good friend with Fats. He introduced me one day and within five minutes, Fats was like, “Want to eat some gumbo?” That’s what he did. He’d liked to cook. He took his gumbo pot with him on the road.

Tell me about a young Dr. John. What was he like?

A lot like he was later. He had words for a lot of things and if you didn’t know what he was talking about, it was hard to understand him. He was just cool. But he had to get out of town. The District Attorney was trying to get him. He had to get out of town or go to prison. He had a lot of fun at that age. It was scary stuff, but he was well-respected for a white musician. He’d play with all the black musicians and it was a great combination.

I met him as a guitar player before he got his fingers shot. And then he started playing piano. Nobody goes from being a great guitar player to being a great piano player, but he did, real easy.

How did you wind up on tour with Brenda Lee?

I was playing in Las Vegas and she was looking for a drummer and I ran into her and her mother. She said, “I want that drummer.” Her mom says, “Who in heavens are you?” But Brenda and the band were looking for a drummer. The one they had, the manager didn’t want to take on the road.

She had a group called the Casuals that played in Vegas. They were really good. When we played the big rooms, they’d hire horns and strings and have big, beautiful big-band arrangements. It was quite a thing. All of a sudden, I got to go see the world.

When I was on the road with her in Japan, she was so amazing. This was 1965 and she had a Number One hit record there. And I was so surprised since people that go there from America usually just learns a few words phonetically. But she was doing talk shows! They respected her for that. Nobody did that before. She was totally fluent. It was pretty amazing.

How did you wind up playing on Bob Dylan’s Self Portrait in 1970?

I was doing a lot of studio work at the time with [producer] Bob Johnston. This is when he was doing some real creative stuff. He was great at putting things together. I think it was with Michael Murphey. But I was doing some projects with him and he introduced me to Charlie Daniels. They were doing a lot of stuff together. That was just a great time.

Back then, I was meeting new people every three hours. It was always a different rhythm section. It was hard to know what was happening. Bob [Johnston] didn’t tell me I was going to work with Bob Dylan. He was just like, “You have a session at 10 o’clock at night.”

You’re credited on clarinet, saxophone, and trombone. Is that right?

Yeah. I can play … Well, not now. I have Bell’s Palsy and I can’t. But when I was in high school, I played clarinet and then drums in marching band.

Was Bob Dylan there?

No. It was just Bob Johnston.

Do you remember much about the session? You are credited on “Early Morning Rain,” “Bella Isle,” “Woogie Boogie,” “Copper Kettle,” and “All the Tired Horses.”

Not really. I haven’t heard the album in years. I moved to New York for a while and I stored all my vinyl in a friend’s basement in New Jersey, but it was destroyed in a flood and I just never replaced them. But my wife Nancy recently bought a bunch of records on eBay that I played on. And she bought me a turntable. I need to listen to that.

Tell me how you met J.J. Cale.

I was doing a lot of sessions in Nashville, Tennessee, in the early Seventies. I knew about Cale, but I didn’t know him. He had this little studio and I was told he’d made some demos by himself. When I heard them, I was like, “This is great.”

In Nashville, most people try to get three songs or even four from a three-hour session. For three hours with cigarette breaks, that’s all it took. J.J. was like, “It’ll take two days to get a drum sound.” I was like, “What?” But Cale was a treasure. Everything fell into place when I got to the Naturally album.

On “Call Me the Breeze,” I can hear a drum machine and your live playing.

Yeah. He cut it with a Hammond, but a lot of it is live. I really got a good response from my brush work on “Magnolia.” And he brought in [bassist] Carl Radle. I had never worked with him before. I went, “This is the bass player I need in Nashville. Where have you been all my life?” He was a natural, great bass player and we locked in really good.

J.J. was so talented and such a great songwriter. Why do you think he didn’t sell more records?

I don’t know if he wanted to. I think he was hiding from success. I remember going to France with him one time and we were having lunch at the hotel. I saw these beautiful French ladies and I brought them to our table. I put one of them next to Cale and the other next to me. I said, “They’re talking about going to your show. Get them some passes.” He started blushing. I said, “Tell them your name.” But he was so shy and didn’t know what to say. He was like nobody else.

Not long after, he was living in an Airstream trailer with his dog. He just disappeared.

He didn’t really want to live the life of a rock star.

No. He’d give money away when we toured. And he didn’t understand how good he was.

Did you do many tours with him?

No. We just toured a little bit. I felt I was missing stuff in Nashville, and I partied too much for them. I didn’t last too long on the road with J.J.

Tell me about recording with Bill Haley and the Comets when you made Rock Around the Country with them in 1971.

They came in and I don’t know if they’d been on tour, but they came in looking like they did in the Fifties. They had the old suits on. I talked to the sax player [Rudy Pompilli] for a while and he told me he had some sort of terminal disease [lung cancer]. It was the last record he played on. I think Charlie Daniels was there, if I remember. Maybe he was just hanging around.

Haley was so talented, but he didn’t really make it out of the Fifties.

Yeah. As I said, they really were in the same suits as when they made “Rock Around the Clock.”

You play on Leon Russell’s All That Jazz and you’re on “If I Were a Carpenter” with Willie Nelson, J.J. Cale, and Leon Russell. That’s a pretty great lineup.

Yeah. We’re in Nashville. I think Bobby Darin had just died and Leon was close friends with him. We did “If I Were a Carpenter” and “Wild Horses.” That was something. “Meet me in the studio. Now!” A lot of sessions started that way. This was before cell phones. I’d be at a bar and it would be like, “Meet me at RCA.”

Did you record with Elvis Presley?

I didn’t do much. We did a gospel thing where he played the piano, but it never was released. I was in the studio working on something and they came in with the crew, Red West and those guys. They brought some guitar cases in and I was going out. Elvis came out of the control room and he sat down at the piano and started playing some stuff. When I went back to get my cymbal case, he had me play a little on the bass pedal and hi-hat. It took off from there. But it wasn’t a contracted session and it was never released.

How did you wind up on the Doobie Brothers record Stampede? You’re credited on “I Been Workin’ on You.”

Having too much fun at a Doobie Brothers concert in Nashville. I was backstage with them. That’s when their opening act was Mother Earth, a group I was playing for. It was a long tour and we were always bumping into each other. I started playing with them back then. Every time they were in Nashville, I’d sit in with them in concert.

One night, it was about 11 p.m. after a show, maybe later. They wanted to go into the studio, so I called a sound engineer and woke him up. He said, “Have you been drinking?” I said, “Of course! But I have some friends of mine that want to record.” He goes, “Call me in the morning.” And before he could hang up, I said, “Doobie Brothers.” He said, “I’ll be right over there! Give me 45 minutes!”

It was just one of those things where we went in in the middle of the night and cut one thing. I don’t think their producer, Ted Templeman, liked the idea because it was done without him. But it ended up on the album.

They were another band I could have toured with. They had a bad reputation. There was a lot of cocaine involved with those guys. Had I done that tour, I probably wouldn’t be talking to you now.

Tell me about playing on the first Jimmy Buffett record, Down to Earth.

I actually knew of him when he was playing on Bourbon Street when I was with Mac. He was playing at a place called the Bayou Room as a solo act. I didn’t know much about his music at the time. When he got to Nashville, he started doing his demos.

I introduced him to Neil when we played the Bridge School [in 2009]. Neil goes, “Do you know Jimmy?” I said, “I got him his first writing deal for Buzz Cason!” And I did. It was $150 a week. I looked at Jimmy, laughed, and said, “I always thought it was too much.” That’s how long ago that was. You could get $150 a week.

That first record is very different than the music he made later.

Yeah. That’s what happens. The more he recorded, the more pineapples were involved. That’s what I call beach music. He got the yuppies. That’s what he wanted. That’s money. They’ll move into his condos too.

How did you meet Neil Young?

What happened was Levon Helm was in town recording [on the sessions for Homegrown]. They were recording at Quadrophonic. They were in there for a couple of days. Ben Keith said, “Come by the studio and I’ll introduce you to Neil. And Levon needs some equipment.” I’d known Levon for years and I said, “I’ll give him anything he wants.” But I was working a couple of times when they were in the studio. I also didn’t want to go to someone else’s studio when I’m not the drummer. I didn’t need to do that, and so I didn’t show up.

The last day that they were recording, Levon said to me, “You gotta come down.” And so I went and he introduced me to Neil. He said, “I gotta go back to New York. Neil needs a drummer.” Neil said, “I really like your snare drum.” [Laughs] Then I go, “I like your pretty guitar.” It was just a great meeting.

But we butted heads that first time in the studio [on December 13th, 1974]. I’ll never forget the look on Ben Keith’s face. They had been playing with Neil there for a few days when I got there. We were doing a song and Neil said, “What’s the drummer’s name?” Ben Keith goes, “Karl.” And Neil goes, “Karl, I think you’re pushing me.”

At the time, I thought I was bulletproof since I worked with a lot of people. I went, “What’s that guitar player’s name?” Ben said, “Neil.” I said, “Neil, I think you’re out of tune.” [Laughs] He smiled and went, “That’s it! I gotta get another drummer!” And he started laughing.

That’s how it is with Neil. We still laugh when we talk, but he’ll go, “Why don’t you call?” I go, “I don’t call anybody.” But he sent me photos of his wedding to Daryl [Hannah].

The first thing you did with him was Homegrown, but he didn’t release it for almost 50 years.

Right! That’s Neil.

Songs like “Vacancy” that you play on are just gorgeous. It’s insane that nobody heard them for all those years.

It’s amazing. My wife has three copies of the album. I promise myself I’ll play it tonight. I haven’t heard it yet.

Tell me about making Comes a Time.

We had a full orchestra for that. We did it at the Castle, which is a real castle in Nashville. And Ben told me to pick three rhythm guitar players, which I did. What happened is that I call three of my Nashville friends. Ben forget that I was going to do it and he got three. When we got to the studio, all these gunslingers were looking at each other. “I play rhythm guitar.” “No, I play rhythm guitar.” They didn’t know each other.

And of course, since I had my pick, I had J.J. Cale. He didn’t want to do sessions, but I talked him into it. And Neil knew Cale. Ben said to him, “We have all these rhythm guitar players. Which ones should be sent home?” Neil is such a nice guy. He said, “We’ll just use them all.”

They set up the guitarists in a circle so they could all see each other play. But there were music stands too and the session was charted out with arrangements. But J.J. didn’t read notes. He didn’t want to do the session, and now he’s trying to get out. I said, “No. Wait a minute.” I said to Neil, “What should I do? Cale is worried because he can’t read.” Neil just says, “Put him in the middle. He can hear what they’re doing and pick something up.” And it worked out great. [Ed. note: J.J. Cale, Bucky Barrett, Grant Boatwright, Johnny Christopher, Jerry Shook, Vic Jordan, Steve Gibson, Dale Sellers, and Ray Edenton are all credited as guitarists on the album.]

The first show you played with Neil was November 12th, 1977, in Miami, Florida.

I remember that one. It was a wonderful time. Neil brought everybody. What I remember most is that it was hot and Neil had a chrome-looking sport jacket.

Neil just wrote on his website that they recently found a tape of the rehearsal and he wants to release it.

Huh. That would be alright with me. It was my first show. I can’t stop Neil. He’s loving all this stuff he’s putting out.

In the late Seventies, you cut 5 and Grasshopper with J.J. Cale. Do you have fond memories of that period?

Oh, yes. It was the same thing. J.J. would go in the studio and it was just like Neil. It was always like, “Next song … Next song …” They probably have a lot of collections of stuff he’s never released.

By that point, he was living in a trailer.

He had a home, but he liked having one that moved.

Eric Clapton made huge hits out of his songs. That must have given him a decent income.

The story is his publisher told him he’d reached a million dollars. He said, “Do you know what I really want to do? Can they lay it out on a table so I can see it?” That’s what Cale wanted and his publisher arranged it. He’d never seen a million dollars and he wanted to see it.

Tell me about reconnecting with Neil Young to make Everybody’s Rockin’.

When they called me up, I said, “What setup do I need for this?” Ben Keith said, “Neil wants a snare drum, a bass drum, and a cymbal.” I was thinking, “What the hell is he doing? Am I playing too many fills? What is he doing?” Then he told me we were going to do a Fifties thing. “What?!” Then he said, “You’re going to have to shave your beard.”

That was kind of a shock. For years, I had sand in my bass drum from doing the video [for “Cry, Cry, Cry”]. He didn’t tell me about the war he was having with [David] Geffen. I was like, “I guess he knows what he’s doing, but what is he doing?”

He really did make the album to piss off David Geffen. He wanted a rock record, so he gave him one.

Exactly. But he didn’t tell us what was going on. I was like, “Where is Neil going with this?”

How was the tour? You’re doing an encore set of rockabilly songs to audiences that didn’t really expect that.

People were kind of shocked since they didn’t realize what we were doing. But then it kind of took off. A funny thing happened with it. We had to have fun with it, I guess. But we had fun doing that tour.

Did you have to get into character as a rockabilly guy?

They put black polish in our hair. We had a wardrobe thing we had to do. It was a theatrical production.

When you did Old Ways after that, it was this big transition and suddenly it was country. How was that experience for you?

I went with the flow and did it the best I could. I could feel that music. It runs in my veins. You can’t predict a move like that, but it’s great when it happens. And Neil didn’t like to do a song more than once or twice. He felt it lost something if you kept going.

Tell me about the tour. It was a lot of state fairs and even some rodeo venues.

It was fun. I had fun with everything I did with him. Neil was the best person I worked with in my life. He was also a good friend. A lot of people can’t say that with groups. But it was great. I’d rather see him now at a dinner with Daryl and my wife than go on a tour, though.

That Harvesters band with Spooner Oldham, Ben Keith, Anthony Crawford, and Rufus Thibodeaux was a great group.

It was fun, interesting, great music. Like Neil says when we speak, there’s only a few of us left.

Tell me about playing Live Aid with Neil.

What a great experience. I saw my friend Doc McGhee there. He introduced me to Bon Jovi. I looked at Doc and said, “He’s cute.” I’m old friends with Doc.

What was it like playing in front of the entire planet that day?

I was pumped up. I remember walking out to the stage and these roadies came over and wanted me to get off this plank I was walking on. But off the plank was mud. They were pushing people into the mud and going, “Get off the plank, Madonna is coming.” Everybody had to jump in the mud. I got into an argument with the roadies. “Fuck Madonna!”

How did you reconnect with Neil for Prairie Wind in 2005? You hadn’t played together for nearly 20 years at that point.

Neil was having a brain problem or something. Of course, that was around the time of [Hurricane] Katrina and I was living in Louisiana. I got my German Shepherd and my RV and I went, “That’s it. We’re going to Nashville.”

I got there early and parked near the studio because I knew Neil was coming to town the next week. It was a weird time with the storm going on and Neil’s health, but everything worked out. It was scary.

How was the show at the Ryman that Jonathan Demme filmed?

That was great. We had everybody in there and it’s a beautiful building. It all went pretty fast. We didn’t do a lot of rehearsing. A couple of the songs that I played on [on the album], Chad [Cromwell] wound up playing on because I didn’t show up for a dress rehearsal. And Neil said, “Let Chad play it.” I should have been there. But I thought those shows were great. Jonathan is a really cool cat and I liked working with him.

How was the week on Conan O’Brien?

I thought that was great. Ben Keith called and said, “You want to go to New York for a week?” I said, “What?” Why did Neil do that? I have no idea. I’d like to see them though if they’re on YouTube.

Your last shows with Neil were the Bridge School Benefits in 2009.

Those were great. It was always great to support those kids. Pegi did do so much for that school, and Neil too. It’s a lot of work and Pegi was getting to the point where it was too much. They had great artists there and you see them pretty close and hear everything. I was amazed when I first did it. It’s not that big of a theater situation.

The band was Rick Rosas, Pegi, Ben Keith, Spooner Oldham, and you. That was just 11 years ago, but only you and Spooner are still with us. It’s really hard to believe.

I know. Elliot [Roberts] is gone too. He was the mastermind.

When is the last time you spoke to Neil?

He actually called me a couple of weeks ago just to catch up. The first thing he said to me was, “Hey, old man!” I go, “Mr. Old Man to you!” He always called me “old man,” but we’re the same exact age. We’re both 75.

He asked about my sound system. I said, “Are you talking about my BMW?” Then he told me how good I was playing with [bassist] Tim Drummond on tapes he was going through and he told me about this new edition of [Homegrown]. He’s got a new house outside of Ontario on a lake. We talked for a while about that. At the end, he said, “We gotta keep in touch, buddy. There’s not many of us left.”

Tell me about your life now. Do you still play drums?

Sometimes I go out and sit in with somebody, but I have a music room with a nice piano and my set of drums and some earphones. I can go in there and play with anybody. There’s a group called Wayne Sharp and the Sharpshooter Band. They’re kind of like the Allman Brothers. I play with them sometimes. That’s kind of fun to do that.

The playing is not bad. The issue is getting the equipment there and set it up. Old drummers have problems. One of them is arthritis in my right hand. But I’m doing the best I can at this age.

The other thing is that the groups around here often mimic other bands and play some other group’s hit record. I don’t want to do that, really. If it was jam sessions and jazz and stuff like that, I’d like that. But to sit in with somebody and do a current country record? I don’t want that.

I can understand that. You’ve played with the greats. It’s an amazing legacy that you should be proud of.

Thanks. There’s a variety of artists, going from George Jones to Neil Young. One time a guitar player gave me his card and it had all his sponsors, his amp company, and all sorts of fine print and a number to get in touch with him. I thought, “That’s sort of busy-looking.” I had one made up that just said, “Karl Himmel. Drummer. Google me.”

Source: Read Full Article