Drink your big black cow and get back in here. Donald Fagen has simultaneously released two new live albums — one under the nearly 50-year-old banner of Steely Dan; one billed as a solo album — that revive some of the most pungently written and exquisitely arranged and played music of the 20th century. “Northeast Corridor: Steely Dan Live!” is the first official live album of material from that band in more than a quarter-century… sans the late Walter Becker, of course, who died in 2017, but performed by Becker with a crackerjack ensemble that makes it sound as fresh as it ever has. “The Nightfly Live,” meanwhile, uses that same big band to revive the full track list from Fagen’s 1982 solo debut, which ranks alongside “Aja” and other Steely classics in the minds of most fans.

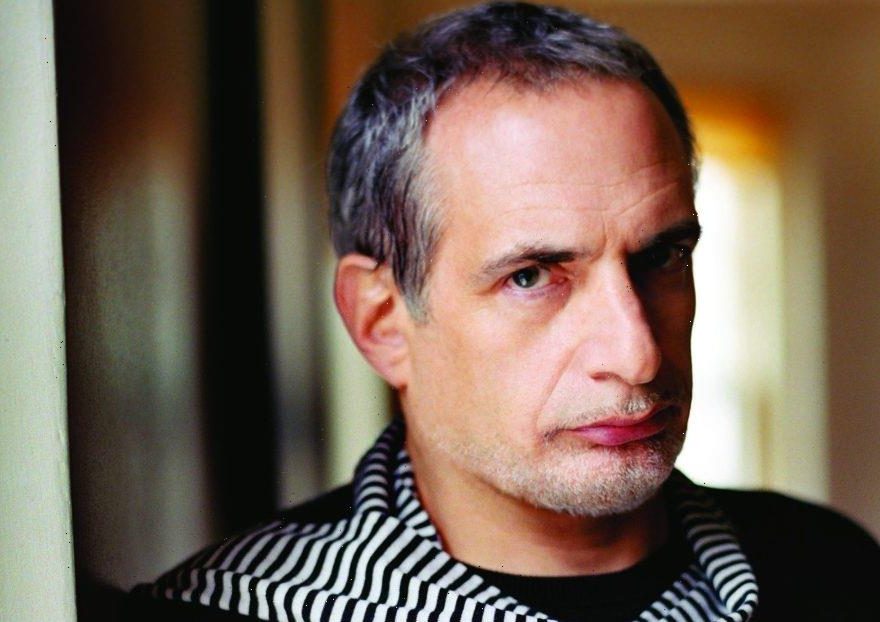

Fagen got on the phone with Variety to discuss the impetus behind releasing the two records, how he feels about continuing to tour as Steely Dan after Becker’s death, when he expects to return to the recording studio and — a recurring theme — his enduring disdain for reverb.

Your fans have clamored for more live albums since the only previous one, “Alive in America,” came out in 1995. But is there any personal satisfaction for you in putting these recordings out?

FAGEN: Back in the fall of 2019, we were at the end of the tour and had 16 more shows, and the band was sounding so good. We’d been out for a couple months, and I thought it should be documented. In a way, I wanted to show off the band. The band we have now has been together like four times longer than the original Steely Dan band, so we really jibe on stage. So I asked the front-of-house mixer if he could make a professional recording off the board, and he said, “I gotta run a few pieces of equipment, but I could do that.” And so he recorded the last 16 shows, a couple of which were “Nightfly” album shows. I loved the way it was recorded: There was a lot of separation, and there wasn’t all this reverb you hear on a lot of live albums. It’s clean. And so I picked the best Steely Dan performances from a couple shows, and most of the “Nightfly” were from one night at the Beacon Theater, but there were a few other better performances I picked for a couple of the other tunes. And, yeah, I thought it came out really good.

Is there anything you feel like you’ve actually improved on from what people remember from the original studio versions?

Generally speaking, it was hard for me to improve on a lot of the arrangements. Some people might think it’s kind of conservative performances. But a lot of times I have trouble coming up with anything better than Walter and I originally imagined. I mean, they are kind of like formal compositions in a certain way. But there’s some great ad-libbed solos, and a few other little knickknacks we added.

I’m really envious in a way of Bob Dylan, who really is very free in the way he tries different things with different songs. I don’t know if it’s always successful, but he certainly has a lot of fun messing around with his tunes. I have differences in phrasing — I have been doing them for a long time, and by now, they may have diverged from the original performances — but not in any radical way.

I remember talking to you in 1993, when you were going out on tour for the first time since you gave it up around 1974. At the time, you said how much more comfortable the routine of touring had become since the mid-‘70s, But looking back, I wonder if there was also a feeling that you were kind of stuck with a band that you and Walter hadn’t really planned to be your band forever.

Well, I wouldn’t say that we were stuck with it, but I put that band together pretty quickly. We weren’t naive, but we were kind of surprised when the record company said, “Okay, now that you’ve finished your first album, you’re going to go out on tour.” For one thing, I’d never sung live, or at least not in any professional way. So I immediately said, “We’ve got to get a singer.” So we called this friend of Jeff Baxter’s, Dave Palmer, and he came out in time to sing a couple tunes on the record. He was good, but it just didn’t work out. And you know, the band wanted to work, and at that point, were really interested and really paying attention to detail and being in the studio a lot. So we started using some session players, people we admired, and went on from there.

It’s great that you’ve been able to settle in with a band of players you really love, because that has to make it more enticing for you, knowing that you still maybe don’t love everything about touring, necessarily.

I’ve gotten used to it. I mean, the conditions are so much better, and everyone in the bank gets along really well, and I’ve been enjoying it more, actually. You know what was really fun was a few years ago hen I did a couple tours with Michael McDonald and Boz Skaggs in a group called the Dukes of September. That was fun because I only had to sing a third of the show, so it was like the perfect amount of singing, and it was like a gas.

When you wrote your book “Eminent Hipsters,” you had some thoughts in there about touring that made some people wonder if maybe you were souring on it again, though it doesn’t seem like that now.

Although basically the tour diary in that book was accurate, I’d come back after doing a show and … there’s a bit of exaggeration for the sake of humor. [Laughs.] But yeah, I was surprised that being in a group that was mainly doing covers and old R&B and soul tunes — and it was advertised that way — we got a lot of flack for not doing more Steely Dan tunes. That was the main thing that aggrieved me at the time.

I figured there might have been a bit of hyperbole for literary effect at times.

Yeah, yeah. [Laughs.]

With this particular set list on this live album, is there anything that’s a favorite of yours?

Well, “Aja’s” always fun to play because there’s a lot of room for improvisation. And you know what I really enjoyed doing was a tune from a later album of ours [2003’s “Everything Must Go,” the final Steely Dan studio album] that’s called “Things I Miss the Most.” And we added an introduction by our trombonist, Jim Pugh, that I think worked really well. It’s a song that didn’t get a lot of play or may not be that well-known, but I think it’s a really nicely constructed tune with really funny lyrics, and I was glad that we were able to get that on the record.

That’s a terrific song because it obviously has the element of humor and irony in how the narrator shifts from talking about the personal things he misses after a breakup to some purely material ones. Yet, at the same time, it doesn’t seem completely insincere.

Yeah, there’s definitely a certain amount of real-life angst in the tune. But there’s something funny about yuppie divorce. As sad as it is when couples break up, then people have to deal with their possessions. There’s something just ridiculous about it. [Laughs.]

Some fans have been talking anew about the two final studio albums you and Walter did after reuniting, “Two Against Nature” (which won an album of the year Grammy) and “Everything Must Go,” partly because they both came out on vinyl in limited editions for Record Store Day this year.

I think they’re on a par with our other albums, for sure. I think they also showed evolution, certainly harmonically. And I think “Two Against Nature” in particular is quite sophisticated. I really enjoyed the soloists, especially (saxophonist) Chris Potter — we gave him a lot of space and he really took advantage of it — and I thought the songs were good. There’s a song on there I really like called “Almost Gothic,“ which is not that easy to do live, for some reason I’m not sure about. And then “Everything Must Go,” I think, was a little better than “Two Against Nature.” It was more live. We went back to just tracking with a live band, and I think it has a lot of great energy and some really nice compositions — “Pixeleen,” and the song “Everything Must Go.”

People get into a routine. The albums they grew up with in the ‘70s will always seem more meaningful or more nostalgic to them. But I think the two albums we did in the 21st century are great LPs. I mean, they’re the best we could do. [Laughs.] We were trying just as hard.

Do you wish you’d done more after releasing that last Steely Dan album in 2003, or was it fine leaving off where you did?

Walter started becoming ill in maybe 2010, and he really didn’t want to (record more). He was having trouble with the amount of production you had to do to make a Steely Dan record. He didn’t want to do that anymore. He put out a couple (solo) albums that I really liked that were maybe more spontaneous, and he enjoyed doing that more. But after a while… I said, “Hey, you wanna write some things? You wanna go in the studio and do some things?” And I remember at one point he says, “You know what I really like to do these days?” I said, “What?” And he said, “Nothing.” [Laughs.] So, you know, I accepted that.

Have you put any thought or effort toward new recordings or new songwriting?

Yeah, actually. During the quarantine, at first I was lucky to get to focus on mixing the live albums. But since then, I was surprised that I have almost an album’s worth of solo material that I’d like to get into recording next year. I really like what I’ve been doing lately, which is unusual. Usually, I have very mixed feelings about whether or not my ideas are gonna work out. But I really think that the things I’ve been writing are really particularly nice, and so I’m looking forward to going into the studio with that.

Obviously, you’re continuing to tour under the Steely Dan banner. But for future albums, will you continue to put them out as solo albums, or…

Yeah, you know, as a writing entity, I couldn’t presume… I’m only 50% of Steely Dan. I would never do that. In fact, I wanted to sort of go out as Donald Fagen and the Steely Dan Band, or something more accurate, but Live Nation said, “You know what? We’re not going to book it if you do that. You have to call it Steely Dan.” And I said, “Well, whatever.” [Chuckles.] You know, I think people understand that Walter’s not there and it will never be quite the same without him. And I couldn’t hope to replace him, but we still have a great band.

People do sometimes get precious when they argue about these things, like, “Well, you shouldn’t call it the Rolling Stones if Charlie’s gone.” They sometimes want to, as fans, impose rules on these things.

Yeah, it’s ridiculous. Also, you can’t ignore the commercial problem where you’re pressured by the promoters and so on. It makes life easier. And I think people understand, basically, unless they’re some sort of internet troll or something that likes to nitpick about that stuff.

We want to ask about “The Nightfly,” of course, because that is such a beloved album and people seem excited to get to re-experience that in a different way with a live album as much as the Steely Dan set. Maybe this is conjecturing and projecting or not, but as hour first solo album, “The Nightfly” seemed in some ways kind of a sweeter album, almost, compared to a lot of the Steely Dan albums that came before it that were kind of…

Snarky? [Laughs.] Yeah. Well, when Walter and I were together, I think there was something more journalistic. I was kind of always playing a part, in a way, in a lot of songs. And in both my albums and Walter’s albums, I think when we’re apart, the albums are just more intimate, both for him and for me. Because when you’re alone, that’s what tends to happen. I wouldn’t say they’re confessional or anything like that, but I think that the approach is maybe not quite as raw as when we were together.

I did wonder if you could have made the same album with Walter, because together, you had such a tough-edged sensibility…

Yeah. But I mean, definitely there’s an edge to it. With something like “IGY,” some people think it’s a benign album about what a great future we’re going to have, but that’s not the way I wrote it. [Laughs.] It was supposed to be funny. And I was hoping that the disappointment that a kid would feel… It’s about, as a kid, the way we saw the future, and what we were fed by the media and government institutions about how great things are going to be and how technology was going to make life easy and save the world, and how things really turned out, and the dark side of technology. That’s really what it was about. So maybe it was a subtler edge, but there was definitely an edge.

Definitely. But just the idea that you were putting yourself in the moment in the late ‘50s in some of these songs, with this feeling of idealism, even if there’s an ironic edge to how it hits you in retrospect…

Yeah, when you use your childhood, I think that has to happen.

I always thought one of your most unexpectedly sweet lines is, in trying to bond with the girl over Dave Brubeck: “I like your eyes, I like him too.“ It’s so coy.

Yeah, I liked that one too. That was funny. Yeah, those years for adolescents’ first love and all that stuff definitely got in there.

On the Steely Dan live set, you have a song that always seemed like a little bit of an outlier in the Steely Dan catalog, which was “Any Major Dude Will Tell You.” That always stuck out as an unusually affectionate song in the catalog.

Yeah, that’s true. I remember I came up with the title, but I think Walter wrote a lot of lyrics on that one, as I recall. Yeah, I like that tune. Walter had a really sweet side, actually. Like on one of his albums [1994’s “11 Tracks of Whack”], he has the greatest song for his son, “Little Kawai,” a beautiful song about a father and son. I love it.

One last question. You end the live album, as you did the sets on that tour, with “A Man Ain’t Supposed to Cry,” and it’s nice that you got an instrumental in there…

Yeah, I love the way the band plays that. I was introduced to that by Chuck Jackson, who was on one of our Rock and Soul Revue gigs, and he had sung that with the Count Basie Orchestra on some album years ago, and I always loved the tune. So I thought it would be a good walk-off instrumental.

Did you pick it just because it was a great-sounding tune, or was there any feeling of sort of wanting to leave people on a slightly wistful note with that song?

Yeah. You know, it’s funny, but it reminded me of… I don’t know how old you are, but when I was a kid, there was a show on TV with Jimmy Durante, kind of a singer/vaudeville-type comic. He was known for his gruff style and rough looks. And at the end of the show, it was like a blackout and then he’d walk off and he’d be in a spot, and then he’d move to the next spot and the next spot as the thing ended. And he had this line: [he does a Durante imitation] “Good night, Mrs. Calabash, wherever you are.” [Laughs.]

Source: Read Full Article