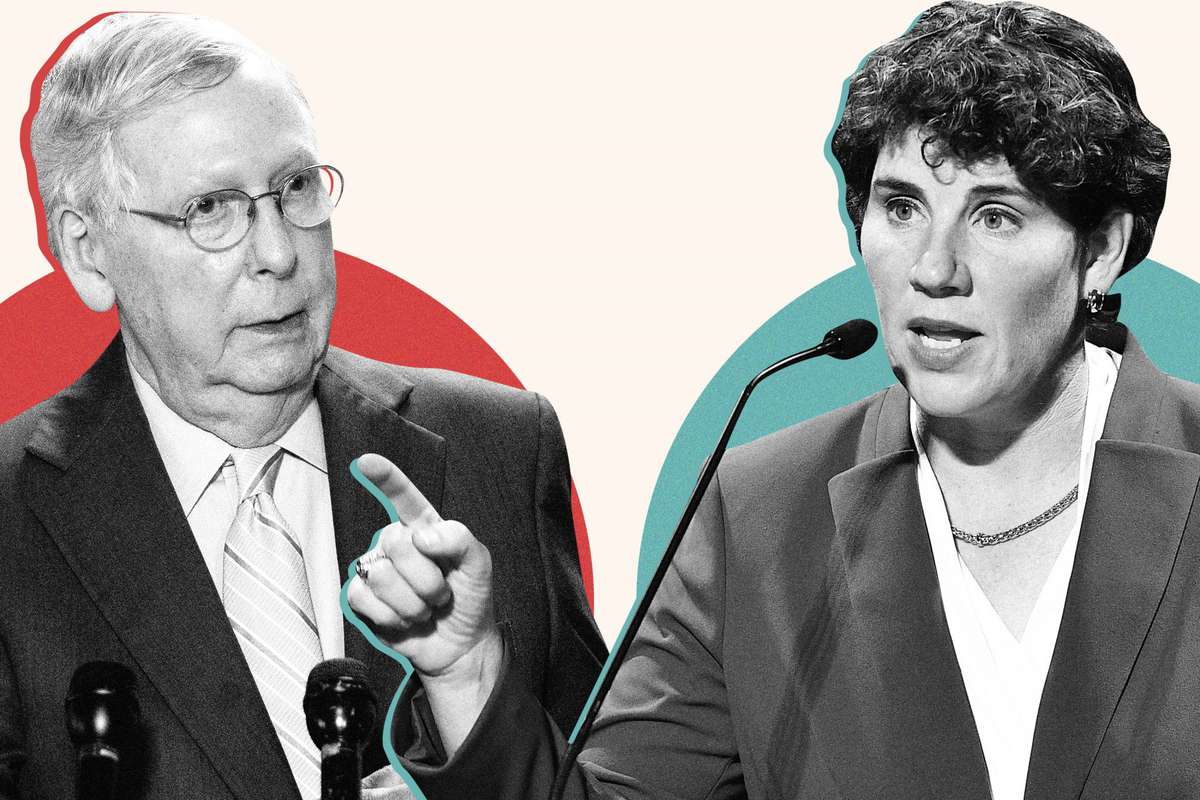

Earlier this month — in what will likely be their only official face-off before Election Day — Democratic Senate candidate Amy McGrath and Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell debated key issues impacting Kentucky voters, like racial injustice and police violence, lack of federal coronavirus relief, and McConnell’s enduring time in office. At one point during the debate, McConnell quipped that McGrath’s campaign could be summarized in a single sentence: “She was a marine, a mom, and he’s been there too long.” Shortly after the debate, the phrase popped up on stickers in McGrath’s merch store.

The debate marked a sort of denouement for Kentuckians: The culmination of several years' worth of McGrath's campaign ads, and even more years of a McConnell reign. (The Senator, 78, has represented Kentucky in congress for 35 years — longer than many progressive voters have been alive.)

Democrats are working tirelessly to get Mitch McConnell out of office, but for some Kentucky voters, his Democratic opponent feels like someone selected for Kentucky (and that’s technically true; McGrath was recruited to run by Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer) and not by Kentucky, given the fundraising, national endorsements, and momentum behind her campaign even before the state got a say in its own race. And now, with just weeks until voters will decide the high stakes race that will have an impact at both the national and state levels, some worry that McGrath, while better than McConnell, is still not the best choice for progressive Kentuckians.

Some Kentuckians have expressed frustration at McGrath’s out-of-state fundraising, and McGrath was criticized for skipping protests calling for justice for Breonna Taylor — who was killed in Louisville, about an hour west of where McGrath lives. She is, however, now endorsed by many Democrats, though her primary challenger, State Representative Charles Booker, was many progressives' first choice. Alison Lundergan Grimes, McConnell’s 2014 challenger, opted to endorse Booker, as did the Lexington Herald-Leader, which has since endorsed McGrath. "[She] would make an excellent senator who would actually put the needs and interests of Kentuckians above her own,” they wrote, explaining that she’s proven to understand Kentuckians are suffering in terms of the economy, education, and healthcare, all of which have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

Other causes for concern include the fact that almost immediately after her campaign launch, McGrath flip-flopped on whether she would’ve voted to confirm Brett Kavanaugh, the Supreme Court Justice who was credibly accused of sexual assault— something several of her higher-profile endorsers, including Senators Kirsten Gillibrand and Kamala Harris, voted against; she also appeared to be in favor of Trump's agenda when she claimed McConnell was responsible for “blocking” him from lowering drug prices and “draining the swamp”; and as recently as this month, McGrath aired an ad in which a voter announced they were voting for McGrath over McConnell, but that they were also voting for Trump for president. The ad aired in Ohio too, which former Vice President Joe Biden — who McGrath endorsed in January —is fighting to win. It was a puzzling move for some voters, many of whom were already struggling to unpack McGrath’s platform.

“I don't really know a lot about her campaign and what she actually stands for, because I don't think I hear that a lot,” Ronni, 22, tells InStyle. While Ronni is actually a registered Republican, she has already voted for McGrath. “I do know if we don't have change, Kentucky will just keep getting forgotten,” she says. Ronni explains she’s from a conservative family, a “middle of nowhere type of situation,” and thinks it is important for people to know that Kentuckians aren’t voting for McConnell “because they're dumb hicks and that we don't know that he's not helping us.” They see him on the news with “Kentucky” under his name, something the Senator himself has used as a selling point, an indicator of his understanding of middle America. But, Ronni says, he has done little to affect the issues she cares about, including healthcare, poverty, and jobs. Ronni also pointed out that she’s heard more about parts of McGrath’s platform — for example, that she opposed Donald Trump's wall — from McConnell's attack ads against her than from the McGrath campaign itself.

“I don't care if you can fly a plane, I care if you can govern,” a small business owner in Kentucky, who asked to remain anonymous, tells InStyle. They were someone who advocated for McGrath, they explained, and were enthusiastic during the first week of her Senate run. But between the Kavanaugh comment and the feeling that she was “anointed” [by Chuck Schumer and the DNC], they described the Senate competition as “every single thing that is gross about the American electoral process all rolled into once race.”

“It should not be a money race," they said, referring to out-of-state help. "It should be a-good-for-Kentucky race."

With an influx of out-of-state postcards encouraging voters to cast ballots for McGrath, and a primary in which State Representative Charles Booker narrowly lost to McGrath, some described feeling as though, even if McGrath was a better choice than McConnell, her campaign isn’t enough to bring swaths of voters to the polls. "We just have not really been engaged enough, and we don't have enough people voting,” explains Cassia Herron, Chairperson of Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, a statewide organization working for a new balance of power and a just society. “And so our work, KFTC's work, over the last few months is just that — we did not endorse in the Senate race. Rather, we are putting our effort into the voter engagement."

Herron supported Charles Booker, and spent months doing outreach to national media to explain why districts of Kentuckians were rallying behind Booker in the primary. “And what was missing about the coverage of the race were Kentuckians,” Herron says, noting the narrative was always about McGrath raising money or whether Booker could reach people beyond Louisville. It didn’t allow Kentuckians to be engaged with the race. It wasn’t until there were “literally Black bodies on the street, that Charles began to get the coverage that was needed for him to raise the kind of money and get the profile,” Herron explains. Recently, she says, a friend who is a narrative strategist helped her think about the McGrath v. McConnell race differently in terms of the opportunity they have for the future: “she described it well — ‘Let's think about it as us choosing our next opponent.’"

Some believe that simply not being Mitch McConnell is a strong enough reason to support McGrath. Audrey, 23, donated half of her summer paycheck to McGrath’s campaign during summer 2019. She explains, “I believe the McGrath campaign is trying their best to show how she can relate to all Kentuckians,” noting that some people she grew up with actually considered giving McGrath a chance when they read statements on her being willing to work with Trump. Back home, she said, she was called “liberal slurs” for the views she possessed, whereas when she moved to Louisville, she was told she was “basically a Republican.”

“You have to think about all parts of Kentucky,” Audrey adds, explaining there’s a delicate balance to approaching such a vast pool of voters. Lanae, 24, appreciates McGrath’s policies around healthcare and public education, noting excitement for a new perspective in Kentucky, and that McGrath being a woman is a plus. “I wish people knew she truly cares for Kentuckians and wants to be held accountable and will listen as a senator,” Lanae adds.

Even amid controversy over whether McGrath is the candidate to finally unseat McConnell, some leaders are already thinking bigger-picture on how to engage voters beyond the context of a single election, part of the work that has to continue long after ballots are mailed, glittery postcards cease, and fleeting national attention on Kentucky politics wanes. Herron says this includes working with officials to get the process right, putting pressure on the state elections board, and talking to local county clerks about what voting should look like in each community. "I think creating this culture where we [are] voting is essential, where we make sure that it's accessible to everybody, and that there is, again, this co-governance model,” Herron tells InStyle. “I often tell people, we are the leaders that we're looking for. We're the leaders that we deserve."

Source: Read Full Article