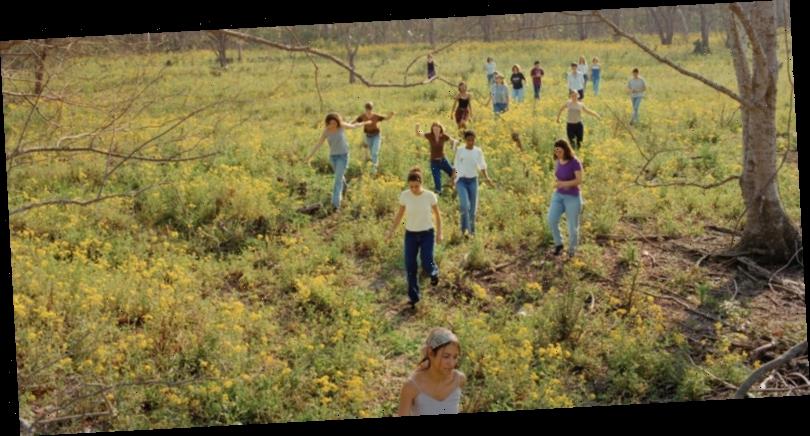

Welcome to Ways of Seeing, where two artists sit down to discuss the nuances of their work, trade industry secrets, and fill each other in on their latest projects. The only catch? One of them is on staff at W magazine. In this week’s edition, visuals editor Michael Beckert chats with Justine Kurland. Originally from Warsaw, Poland, the photographer now resides in New York City. Her book Girl Pictures, which hit shelves in May, depicts young women she shot while road tripping across the North American wilderness in the Nineties and early Aughts.

How did you go about casting/finding these girls to photograph?

There were many different instances. The first girl I photographed, Allysum, was the daughter of a man I briefly dated. Laurie Simmons, my teacher at Yale, introduced me to her kids’ babysitter, Lily. I stopped girls on the street, in front of high schools, or in parks. And each girl knew other girls, so they would bring their friends. When I started traveling to make the work, it got harder. My mother worked a Renaissance Faire circuit, so I found girls that way, or through friends of friends, but I continued asking people as I found them. A high school in Vermont let all girls get out of first period to be in a shoot.

How old were you when you started taking these pictures?

I began Girl Pictures in the summer of 1997, which would have made me 27.

Today’s younger photographers face so much pressure to constantly release work on Instagram. What was pressure like for younger photographers in your day?

Photography has always been a numbers game, the more pictures you take, the greater your chances of making something worthwhile. It depends on the confluence of so many factors: light, circumstances of an event (staged or otherwise), being in the right place at the right time, lucky accident, athleticism. I think all photographers have a pressure to make a lot of work.

My father used to talk about a young artist as being in a heroic period, that they have to work as hard as they possibly can to see what they are made of. Often they spin their wheels and make sloppy work. But then they have the rest of their lives to comb over what they’ve made. He said the heroic period is about setting the outer parameters for the work you’ll make the rest of your life.

Instagram is something else. It’s instant gratification, but the number of likes does not correspond to a more thought-provoking or nuanced photograph. I get more likes for pictures of my cat than any piece of artwork I posted because other people have and like cats.

A difference I’ve noticed with my students has to do with the fact that digital images are free. Sometimes a student will take a hundred pictures of a single subject, certain that with so many exposures they have a great photograph, or the one they need. In these cases usually the first one is the strongest, and then as their attention diminishes, so do the photographs. It costs me $10 every time I expose a piece of 4×5 film (although the girl pictures are 6×7, so considerably cheaper) so I make sure I’m not wasting my money. Most bad pictures happen when the photographer’s attention has wandered away, when they aren’t engaged in translating what is in front of them into a two-dimensional image.

Are the scenes portrayed in this book emblematic of your own girlhood? Are there similarities?

I have an extraordinary family. My mother, a seamstress, taught me to live on the road. My father, a painter and a hunter, taught me about the woods. We were incredibly poor, living on welfare checks that never lasted through the end of the month. But both my parents had made choices to live by a set of values, not religious—but ethically and spiritually motivated. They were artists. One of my sisters grew up to be a dancer and later a stylist, the other a civil rights lawyer who has won landmark discrimination cases. The fantasy of a teenage girl runaway certainly comes from my iconoclastic upbringing.

But films and television, literature and music also influenced these pictures—a collective fantasy of the teenage runaway. They were made in collaboration with the girls who brought me to their secret places and improvised in real time.

When you look back at these pictures now, do you see the process of making them, or are you able to fully live inside the narratives they’re depicting?

When I pulled the box of prints down two years ago for an exhibition at Mitchell-Innes and Nash (which became the book) I was embarrassed of the pictures, the way you might be embarrassed of a high school yearbook: of the longing, earnestness and sentimentality of my younger self. Although I can clearly see the political (and homoerotic) continuity in my work, it’s as though someone else made those photographs. They live in the world now and belong to the people they speak to, and the girls in them as much as they belong to me. That’s the distance of twenty years.

Did you feel like a friend of the girls’ once you started taking pictures, or did you ever feel uncomfortable?

Photography allowed me to dream of new possibilities, a future I wanted to live in. It was incredibly affirming to find other people who wanted to collaborate in my fantasy of a girl utopia. Not all the shoots ended up working as photographs—actually, I probably have a very low success rate. But the time we spent together, scouting locations and staging narratives, would be charged with excitement. Some of the girls (especially the ones in New York, where I lived) became friends over time. Once they agreed to be in the photographs, it was never uncomfortable, but sometimes I felt shy to ask them. Rejection always hurts.

Does befriending a subject mean seeing your picture of them differently as you come to know them better?

No, I don’t think so. The pictures aren’t portraits. The girls presented how they wanted to, not how they were. Some girls I hardly knew came alive in the photographs, while others I knew well might freeze up. I purposely photographed at a distance, giving them a certain privacy and letting them express their way of being with each other.

One of the girls died, so her pictures take on a different weight. The ones I still see, who I’ve watched grow up, also feel different because I can compare them to their younger image.

This entire book was photographed in a world without iPhones, and I find it particularly interesting that we don’t see a single girl interacting with technology here. These pictures do make me feel nostalgic for a time when people were more present with the friends and environments around them. I’m wondering if as technology has become so ingrained into the girlhoods of today, if you see these pictures any differently than you did when you first took them?

When I made these pictures I was very interested in the ways girls pretend to be girls. That identity formation involves a certain posturing, and in front of the camera the girls were aware of what they looked like in relation to an understanding of girlhood. With the advent of iPhone selfies, the posture of the teenage girl takes on a new form: the camera is held by the individual girl at arms’ length from above and maybe they hold their fingers in a “V.” It’s easier to see the technology easier because it’s newer, but my pictures also involve certain technologies, even if the aesthetic is anti-technology.

When you photograph girls, or anyone these days, do you find that they have a more rehearsed posturing, considering everyone has become so self conscious of the way their image translates in an image now? Do you try and break this posturing via your own direction, or do you embrace it?

I don’t photograph girls anymore. I haven’t since this series. But I do feel people are more self-conscious and more suspicious. Either because they know I will publish the work or because they want to be the one to author their own image.

Has their meaning changed for you as they’ve aged and become relics of a pre-digital era?

Yes, definitely. But the fate of all photographs is to become past tense. The second you take the photograph, its context starts slipping away. It stays in one place in time while we speed into the future. But hopefully this book of Girl Pictures will have some influence on what a future for girls (and women) could look like.

All accolades aside, what are you most proud of so far in your career as an artist?

My feelings are of gratitude, not pride: to the girls who collaborated with me and to other travelers who helped me along the way. I’m lucky to have spent so many years making work in the various forms, to have been supported by Aperture, my gallery, and collectors. I feel honored to be given critical attention. I love my students, who keep honest and tuned in. I don’t have any money but I feel incredibly rich.

Related: Artist Elliott Jerome Brown Jr. on Making Work in the Margins

Source: Read Full Article