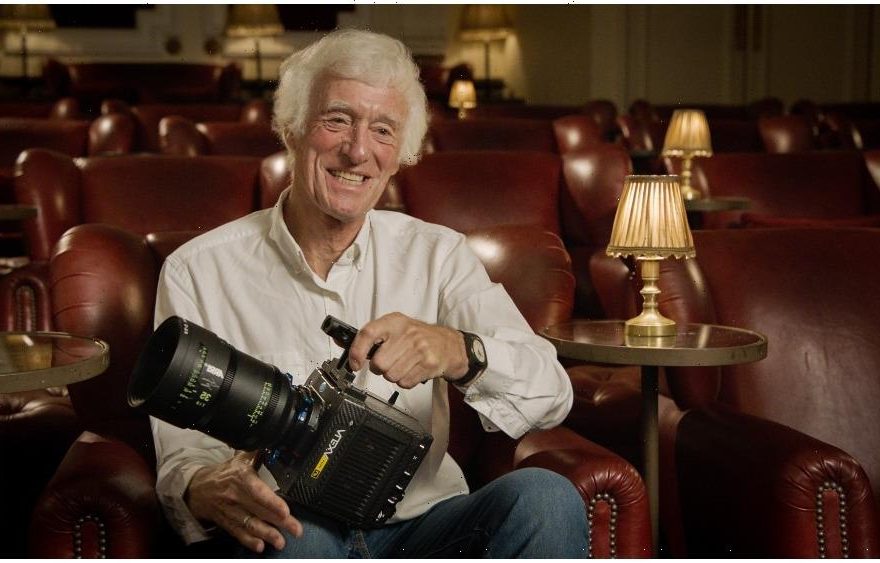

Two-time Oscar-winning cinematographer Roger Deakins is best known for his effective and simple camera work on films such as “Skyfall,” “Blade Runner 2049” and “1917,” on which he collaborated with directors such as Sam Mendes and Denis Villeneuve. His images simmer and he has provided some of the most visually delightful scenes on film.

Considered a master behind the lens, Deakins has made an impact on the industry as he presents timeless works of art through his cinematography.

His new project, however, is a personal one. “Byways,” publishing Nov. 2 and available to pre-order, is a compendium of photos from Deakins’ private collection. Spanning five decades, the hardcover curated by Deakins and Damiani books is a snapshot of single frames from the beaches and coasts of England to field shots in Germany while on set. The images capture his love for the enigmatic.

Deakins talks about why he gravitates to black and white photography, the inspiration for his book and shares his thoughts on iPhone photography.

What’s your earliest memory of first picking up a camera?

I’m pretty sure I never touched a camera until I went to art college. It was there that I discovered photography. I went to art college and they put me in a graphic design course which really bummed me out because I wanted to be a painter – I suppose they knew better.

As part of graphic design, one took photographs as a way of creating a book cover, it wasn’t taking photographs for their own sake. When I started taking photographs, I realized I wanted to do a bit more with it and just take photographs for the sake of taking photographs.

The photos in the book are all in black and white, what was it about shooting in monochrome that you were attracted to?

I can’t get my head around shooting color. I’ve talked to a couple of photographers and they think it’s very strange. I guess I was brought up admiring the great photographers who worked in black and white, and when I started doing it myself just the processing of color and printing was complicated so I think that pushed me down the avenue of doing black and white.

When I was in art college I smuggled out the key and had it copied so I could go in the darkroom at night. I would go off by myself wandering around during the day with my camera and then at night I go in the darkroom when nobody was around, and had the best of both worlds. I think it was easier doing black and white.

We’re in an age where we take so many photos on our phones that never see the light of day, but something is missing about going into the darkroom and developing photos or going to get film developed. What are your thoughts on the changing way in which we take photos?

I have friends that go on holiday and all they do is take photographs. I don’t think they actually ever experience where they are until they get home and they look at the photographs but sometimes they take so many I can’t imagine them ever going through them all.

I take very few. I might go out for a day wandering around with my camera and might not take a single image because nothing’s really drawn my attention. I don’t have rolls of negative anywhere and I don’t have huge files on my digital images. I’m very selective it is that’s the way I’ve worked as a cinematographer with directors.

I haven’t really worked with directors that shoot millions of takes or multiple coverage of a scene. The directors I work with understand the one angle that tells the story the way they want to tell it or one angle for any particular moment in the scene. It’s not a matter of getting five cameras and shooting coverage, and I’m like that with a stills camera.

How did you decide to turn your photos into a book?

It was important to me that this had nothing to do with my real work. This is a sketchbook. I had toyed with the idea of doing a book exclusively on the seaside of Southwest England because I spend a lot of time there, and I grew up there and I love it. I was trying to amass enough photographs to have that as a book, but then I thought, ‘Well, that’s going to take me a long time because I’m not very quick.’

I had these photographs from various parts of the world that I like, and they’re personal to me. I thought, ‘Why not make a book?’

I’m very lucky that Pete Franciosa got behind it, and he found a publisher (Damiano in Italy), and they were supportive of the idea. A few had said they had liked the idea of a book, but they wanted it to be about my film work. I wanted it to be free of my work as a cinematographer, so it was really great when Damiani came to me and said they liked the photos.

I say in the book that I’m not a photographer and don’t consider myself one. It’s a very different world. The great photographers have dedicated their lives to taking still images and I’m not known for that, so for a publisher, I think it was a step in the dark.

Can you talk about the cover image with the grass and the two hands leaning out the window?

I’m drawn to images that are enigmatic that the viewer wonders what it is. I don’t even know who that was leaning out that train. I was in Germany and we had been filming on this period train. It was probably a crew or an extra leaning out of the window. Sometimes I don’t know why I’m drawn to something but I just connected with it. Sometimes an image is more literal in a way and I can understand what’s drawing me to it, but that is not. Just the pose of the hands and the feeling of the steam from the train, something just attracted me to the image and I just took a frame.

What was it like going back through these memories of 40 or 50 years ago?

It was really nice revisiting the photographs I’d taken in North Devon. I worked there for a brief period for an art center in North Devon. I have to say, I did a really bad job because I think I was supposed to be recording things for history, but I was taking photographs for myself and that is slightly different. I took some photographs that I really like. So that was interesting going back to those photographs, and then selecting ones that might not be for the archive where they are and they might not be the first choices because they don’t show a village square or they’re little moments, but they are things that I’m attracted to, so it was nice to rediscover those and let them live on the page.

There’s another image from Weston Super Mare which captures British weather in a nutshell. What was the story behind that?

I often go to a Western Super Mare and just wander the seafront. This was late summer and it was pouring with rain. I saw the poster at the bus stop and on the beach. Beyond this is a shellfish stall with tables laid out. I thought that’s a wonderful frame, but it needs something in it. I went back and forth the whole day, and I photographed a couple of different people in the bus stop, and this lady was there with the umbrella. I was standing looking, and she was looking at the poster. I only took one frame, but it’s such an enigmatic shot. You wonder if she’s shocked by the naked lady lying face down in the sun or is she dreaming of being somewhere else other than Western Super Mare.

What was it like to see the final book?

I have to praise Damiani because they were fantastic. It was great to work with them and select the photographs and get some sort of rhythm.

It has rejuvenated my love of photography. We’ve been in Devon for a couple of months. I feel like I’m starting from scratch and I can start a new chapter because the ones I’ve taken are in the book, and that’s it. I’ve already taken some photographs and I get as much joy and kick out of it as I do after a day’s filming. I can take one frame of a photograph and come home and I’m really kind of tripping.

Have you tried shooting stills in color recently?

I made a couple of prints in color and it doesn’t work for me, so I reprinted in black and white.

What is the relationship between photography and cinematography for you?

It’s hard to know who and what your influences are, isn’t it? I’ve certainly studied photography, different photographers — mainly street photographers and photojournalists, but to say they’ve influenced what I do. I couldn’t point to anything specifically. Unless directors are looks for something as a visual reference.

I’ve been more influenced by painting and painters than I have by photographers. in a way, I think. I love Giorgio de Chirico and I don’t know why. There’s just something about the simplicity of his paintings and the use of different elements that seem out of place with one another. I like trying to do that in my photographs, and I think that is something I’m conscious of trying to do. You see it in the bus stop photo, juxtaposing different images with the young girl in the poster and the harshness of the bus stop. It’s just this contrast of shapes and ideas.

Source: Read Full Article