In 2018, Compton-rapper-turned global phenom Kendrick Lamar won a Pulitzer Prize for his album DAMN. — but it's not his only work that will be written about in history books. Three years before, as Americans took to the streets once again to speak out about racial injustice and a systemically-flawed police force, they found their protest anthem in Lamar's "Alright."

The hard-hitting chorus, "We gon' be alright," channeled protestors' rage as they shouted it on the streets. Soon, videos of protestors chanting and thought pieces about the song's connection to the Black Lives Matter movement flooded the internet.

Today, the music video of "Alright" — with its graphic black-and-white imagery and pointed criticism of police a form of protest in its own right — has more than 135 million views.

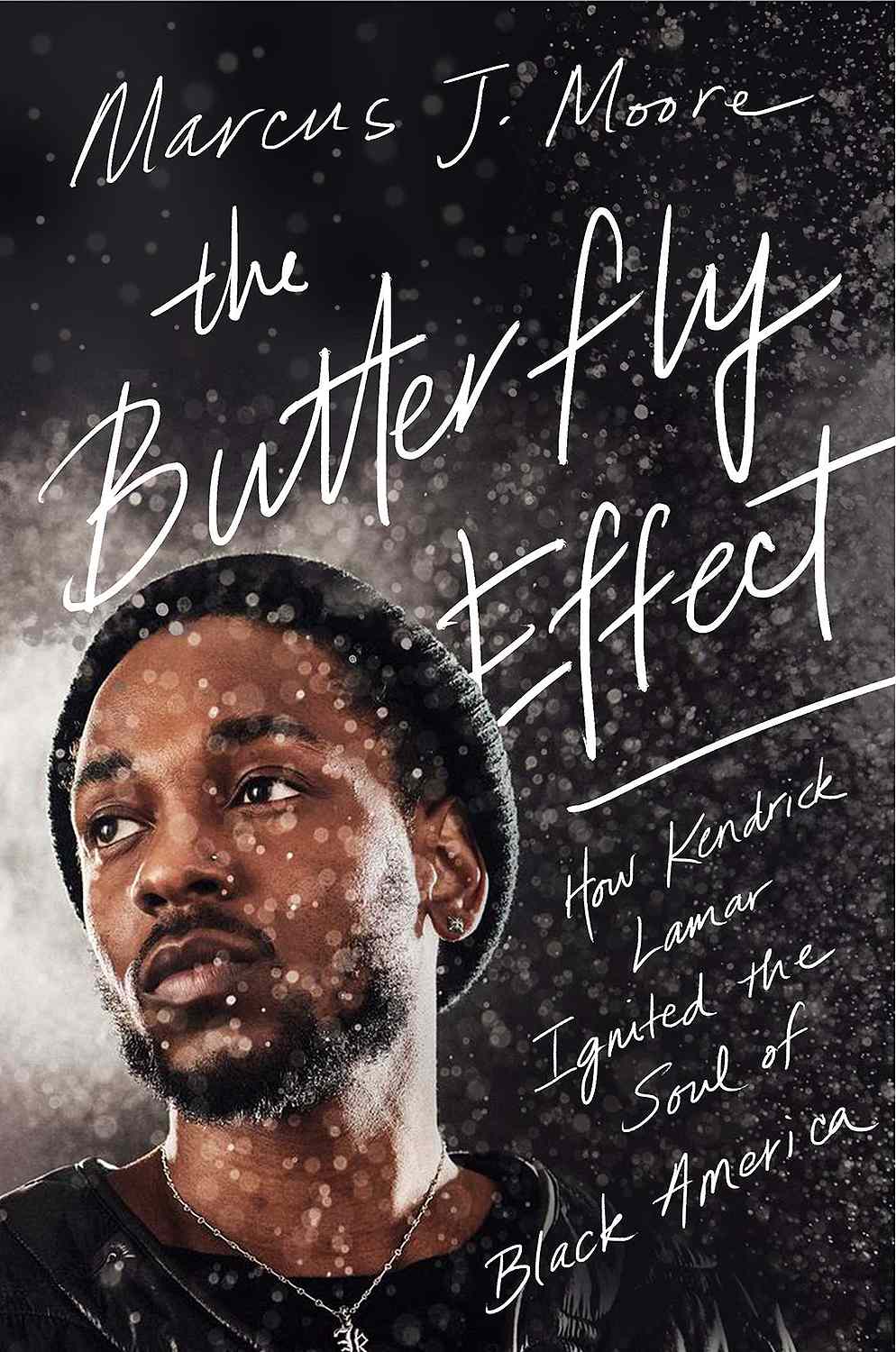

"The long-lasting impact of 'Alright' isn't on the Billboard charts," says Marcus Moore, author of The Butterfly Effect: How Kendrick Lamar Ignited the Soul of Black America, in an interview with PEOPLE. "But I feel like it has a longer-lasting impact because it was chanted by the people for whom the song was made. It was being chanted by people in the street who out there actually doing the work."

The book is a comprehensive look at the 33-year-old rapper's life and an insightful analysis of Lamar's place in the larger musical landscape — from the distinct music flowing from L.A. to his place amongst other hip-hop icons like Kanye West and Drake. It also traces Kendrick Lamar's lasting impact on the fight for racial justice.

Moore, an award-winning music journalist who has written for outlets like Pitchfork and The Washington Post, argues that Lamar's music speaks to vital emotions of the human experience, so that 20 years from now, people will still be listening.

"I really wanted to show people that even though he has earned the right to be looked at as the 'Rap Messiah,' he found something that he liked, creative writing, and just stuck with it," Moore says about why he wrote the book. "And, if you find something that you really enjoy and put in those 10,000 hours to be an expert at your craft, you too can ascend to the level of a Kendrick Lamar."

Moore writes that Lamar (born Kendrick Lamar Duckworth) was a quiet kid growing up in Compton, who escaped the dangers of a gangbanging culture that entrapped so many of his friends. What set Lamar apart, even from the beginning, was his unflinching honesty in a genre that has increasingly become "celebratory," Moore explains. And, later, the rapper's incorporation of a plethora of other genres.

"When I listen to Kendrick Lamar, I hear nods to N.W.A., I hear nods to Tupac and OutKast and the spacious sound of OutKast and Goodie Mob and all those old Dungeon Family records," he says. "But he also has this knack of catering to new school listeners as well, where he has these really big booming beats that ring out in nightclubs and open-air festivals."

Lamar captured a global audience with his intricate lyrics and riveting sound—often including a deeper meaning to even club hits, as he did in "Swimming Pools (Drank)," in which he addresses alcoholism. He also opens up about heavy topics like depression and survivor's guilt in his music.

"When I talk about Kendrick's survivor's guilt, he was becoming successful at a time when he hadn't really ventured outside of Compton much at all," says Moore. "So, as a result, he was trying to figure out why he was the person to make it out. Why he was the person, out of all the talented MCs in Los Angeles, why he was chosen to be the one? Honestly, I think it was just a whole lot of goodwill and a whole lot of good luck because he had people looking out for him."

He adds: "I think it also comes up in his spirituality as well. He often asks the question like, 'Why me, why am I the person?' And I think he's still trying to wrestle with that."

While Lamar's identity as a Black American is intrinsically tied to his music, it wasn't until his tour in South African in 2014, that he started to write more consciously about the larger Black experience, Moore explains.

"He was going to parts outside of Cape Town and Johannesburg and was connected with real people," the author explains. "It wasn't until they went to South Africa and started hearing a different vibration there that he realized that he needed to do something totally different."

The result was the Grammy-award-winning album To Pimp a Butterfly, and his "unapologetic" song "Alright" that would quickly transform into a protest anthem.

"That's when he realized that there were bigger issues at hand, coupled with the fact that, especially in the streets in the United States, you had unarmed Black people being killed by police at an alarming rate," Moore says of Lamar's trip to South Africa. "You had protests, you had acquittals, you had cops being acquitted for crimes they shouldn't have been acquitted for."

"It was a lot goin' on, and still to this day, there's a lot going," Lamar told producer Rick Rubin in a 2016 interview of creating "Alright." "I wanted to approach it as more uplifting but aggressive. Not playing the victim, but still having that, 'Yeah, we strong.'"

While there are other popular protests songs, like N.W.A.'s 1988 "F— Tha Police," Moore says that "Alright" struck protestors because the timing was right and it was mainstream—many knew and loved the song. The song went viral after a protest in Cleveland in 2015, and after it was chanted during other protests across the country.

Wouldn't you know

We been hurt, been down before, n—-

When our pride was low

Lookin' at the world like, ‘Where do we go, n—-?’

And we hate po-po

Wanna kill us dead in the street for sure, n—-

I'm at the preacher's door

My knees gettin' weak and my gun might blow

But we gon' be alright.

-The pre-chorus from "Alright"

"We needed something like that, that you could chant and you could just get whatever stress off your chest you needed to. And that was the perfect song," Moore explains.

“You have these two different elements colliding at the same time. You have soul music, which is Black music. And you have very aggressive rap lyrics as well," he continues. "That's what I meant when I [wrote in the book], 'It was a middle finger to the man.' Because it was. It was unapologetic. And I think that's what we needed at the time."

Slate culture writer Aisha Harris wrote an opinion piece about the song's power in August 2015.

"I've been returning to this song again and again this spring and summer. In part that’s because 'Alright' is just damn good ear candy, with its breezy Pharrell-produced harmonies, its swinging, laid-back production contrasting with Lamar’s skittering wordplay," she writes. "But I also listen to it because it's been a long and difficult year since Ferguson, and the world sometimes seems like a terrible place, and I need Lamar's reminder that we've been down before."

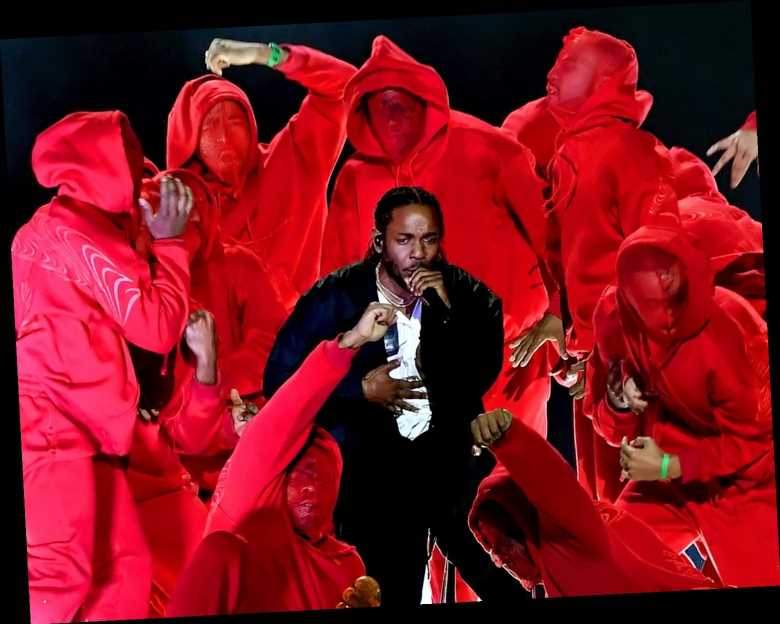

At the 2016 Grammy Awards, Lamar stole the stage with a performance that began with the star and his bandmates walking out as part of a chain gang and locked inside jail cells — it was both art and a cry for justice.

In 2018, he released the soundtrack for a major milestone for Black culture, the movie Black Panther. That same year, Lamar won the Pulitzer Prize for DAMN. He was the first rapper to win the award and the first winner who didn't fall under the genres of classical or jazz music.

Lamar said it was "beautiful" to get such recognition.

"The time was right," Dana Canedy, who oversaw the prizes, said at the time, according to The New York Times. "We are very proud of this selection. It means that the jury and the board judging system worked as it's supposed to — the best work was awarded a Pulitzer Prize. It shines a light on hip-hop in a completely different way. This is a big moment for the Pulitzers."

But Moore explains that the rapper's win "does more for the Pulitzer than it does for hip-hop."

"For whatever reason, even though hip-hop is an established genre, there's still a segment of people who don't see hip-hop as real music," he says. "Too bad for them. Because it is. I don't look at it as, 'Oh, well now Kendrick's validated.' I look at it as, 'Okay, well good for y'all for getting on the boat because he's been here.'"

Source: Read Full Article