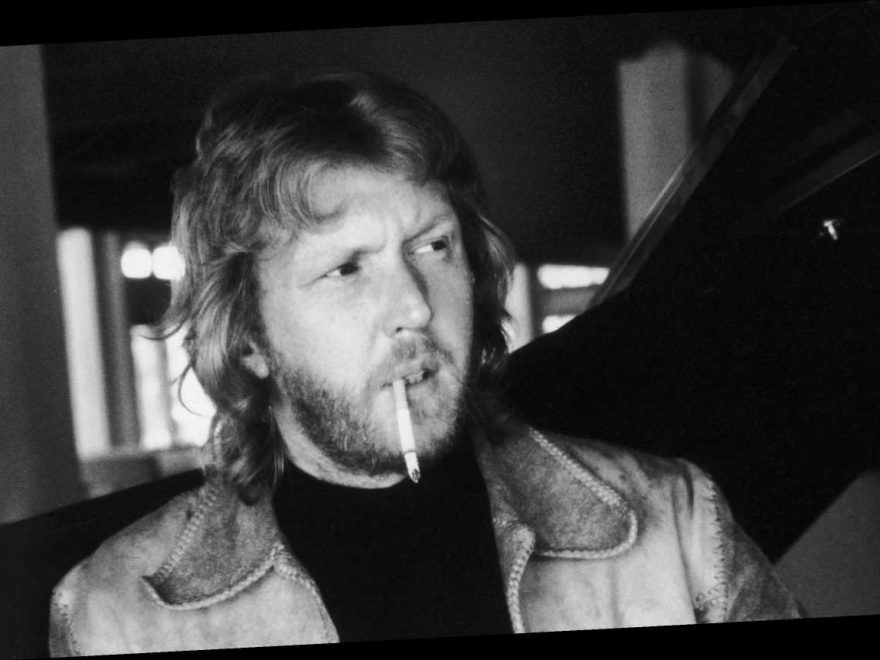

Twenty-five years after Harry Nilsson died from a heart attack, a new posthumous album, Losst and Founnd, has been assembled from material he recorded in the latter stages of his career. Amazingly, it’s the first time the public has heard new material from the singer-songwriter since the release of his 1980 album Flash Harry. To commemorate its release, the four-part podcast series Final Sessions has been created to trace the story of how it came together.

The demos that form the core of Losst and Founnd were recorded in the late Eighties as well as days before Nilsson’s death, when his voice was noticeably different than in the 60s and 70s — it’s deeper, gravelly and weathered. “His wings were clipped,” says host and Billboard editor at large Joe Levy. “There are some tracks where it seems like he’s mapping out a future for that voice.”

“I think what you hear is a guy who wanted to keep going,” Levy continues. “He had to for certain financial reasons, but he also wanted to, and you hear that struggle. You hear that sense of taking a step forward with difficulty where you used to be able to run. And that to me is moving.”

Were you a big Nilsson fan going into this?

I’m a big fan of the early records. I came up having to work hard to hear certain records that weren’t around so easily in the days before streaming. It wasn’t the easiest thing to find a copy of Pussy Cats for awhile, the record he recorded with John Lennon [in 1974]. The revelation to me was digging in hard to the later period records, everything that followed Pussy Cats.

Popular on Rollingstone

Because the common narrative is that he blew out his voice recording with Lennon, and the later records therefore just aren’t as good because that amazing three-and-a-half octave voice is no longer there. Whereas the truth is that there’s an incredible number of great songs scattered across those later period records. The production is completely fascinating. He leaned hard into his way of working, which was to go into the studio with some cocktail napkins that had a couple of lyrics and a few ideas on them [with] Dr. John and Van Dyke Parks and spend 12 days figuring out how to translate that into a song. Just to walk into the studio with his wit, his lyricism, his sense of melody, and explore. And those later records have great explorations on them.

So why do you think it’s such an untapped area of his catalog?

There’s two reasons. Except for [1977’s] Knnillssonn, the second to last one, I’m not sure any one of them is a great listen all the way through. But also, I think there’s a sense of the world moving away from Harry and Harry moving away from the world. Pop music just began to go in a different direction. And there’s a moment where he’s at the center of a lot of pop, a lot of rock and roll. Every single Beatle has a personal relationship with Harry. Every single Beatle loved him in a different way. Every single one of them. Ringo is his closest friend in the world.

Wasn’t he the best man at Nilsson’s third wedding?

Exactly. John was Harry’s hero, and it’s absolutely clear that the two of them saw certain twinned impulses in each other. Paul leaned on him to write a song for Mary Hopkin, which Harry delivered overnight. George and Ringo both record on Son of Schmilsson with Harry. And I’m told that there are other sessions with George that we haven’t heard.

And of course, George is at the funeral, which is held just after the LA earthquake in ‘94. And the famous story is that as they’re standing over the casket, George says, “Fuck you.” And everyone looks around wondering if he’s upset. And in fact, he’s leading them in a chorus [of “You’re Breakin’ My Heart”], in the singing of “You’re breaking my heart/You’re tearing me apart/so fuck you.” Which in a weird way, is an enormously fitting send off. God bless George Harrison, this is actually an appropriate thing to say for heartbroken people in a moment of grief.

So every single Beatle. Think of being the guy who gets the phone call in 1968 to come over to England and hang out while they’re recording what ends up being “The White Album.” The guy who, when they’re announcing the formation of Apple Records, is anointed their favorite artist. And when somebody else says, “What’s your favorite group?” He’s going to be that, too. I mean, he’s right in the center of it in ’67, ‘68. And that’s before he becomes a really massive star in 1970.

The later years are in stark contrast to that.

So in the later period, there’s a sense of him pulling away from the world of pop. He’s climbed the mountain, and once you climb the mountain, you got two choices. You can decide there’s a bigger mountain out there, or you can go down the other side. And I think Harry went down the other side. He didn’t really care about making another album as perfect as Nilsson Schmilsson. He indulged his sense of humor, he laid certain booby traps in his best songs. If the punch line to one of your best songs on the follow-up to your massive hit is “Fuck you,” you’re not gonna get that one on the radio. It’s brilliant. It is exactly what should be in that song. The not the best way of making another hit. I think he leaned heavy into his art and heavy into the sense of humor, and less heavy into commanding the radio or the charts.

And so people don’t pay a lot of attention to those later records, whether there are great pop achievements on them or not, and there are. I think it’s not until we get to alternative rock guys in the 90s, the early 2000s, pointing to Nilsson to some of those later records as deserving of not just consideration, but study. And distance can give you clarity on work that seems muddled or disappointing at the time. And that’s the thing about records in general. They arrive into a marketplace and they’re either validated by the marketplace, or rejected by the marketplace.

You’ve had a career in music journalism since 1988. What did you learn from making the podcast?

It’s a different way of telling the story. The challenge and the learning process was twofold. One was how to use the story of this record to also tell the story of his life and career. And the second was how to integrate what for me would be usual critical insights into more of a narrative piece.

I think there were a couple of remarkable moments for me where I came to understand in sitting down and writing the script for the podcast, [like] certain things about his Beatle obsession. The way for instance, his cover of “She’s Leaving Home,” which is generally considered not one of the great things he did, but the way that it really reflects the story of his own life. Harry was someone whose father left home — he had discovered that within the year of recording that cover. His mom has left home, and Harry himself at 15 had left his uncle’s home. Everyone left home. So there’s this nuance that on the one hand, the cover doesn’t quite work as well as the Beatles, where Paul sings one part and John answers singing another part. Harry sings both those parts and there’s a sort of flattened quality to his version of “She’s Leaving Home.”

On the other hand, emotionally listening to it, I began to think, “Wow, he’s singing both parts because he’s lived every part of the songs. He’s seen it from all angles. He’s been sort of the voice of the parents in this song and the voice of the narrator and he’s lived the life of the girl who’s leaving home, the one who’s setting out to get away from things. He’s lived every part of this song. And that, to me, was really interesting, and super fucking nerdy. I’ve written about music for a long time. It’s really nice to be able to talk about music while the music is playing.

Nilsson’s son Keifo plays on the record, and he also appears on the podcast. What was that like?

Kiefo is a gifted and analytic musician. He’s someone who’s made a study of his father’s music. If you go to his YouTube page, you can find some videos he put up a few years ago. He’s done his dad’s songs. He does a live scoring performance of The Point! So he really knows this music well, and he had interesting things to say about the music, particularly songs like, “Think About Your Troubles” and other songs in which follows some of that same Nilsson-esque journey, that navigation between the dark and the light. And that happens a lot in Nilsson’s music. That sense of the words describing something painful and the melody lifting the whole thing up.

Nilsson’s music has been prominently featured in film over the years — from Midnight Cowboy to Goodfellas, and You’ve Got Mail to Practical Magic — but he’s sparked a new interest in the last decade, like in Russian Doll. Why do you think that is?

The intersection of Nilsson and film and television are the way in which Nilsson’s songs beautifully fit into soundtracks, that’s not a recent revelation. I mean, we know that he’s the one singing the cover of Fred Neil’s “Everybody’s Talkin’” on the soundtrack to Midnight Cowboy. What we might not be thinking of is how many other times he went down that road. He does the theme to The Courtship of Eddie’s Father. He turns up singing on a different sitcom, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir. He does the soundtrack to this Otto Preminger movie Skidoo. He dreams up The Point! and then goes hard on his hustle to sell the idea to ABC to turn it into an animated feature. So he understood what it took to make music for TV and movies, and he did it well.

If in later years other directors are recognizing that, no surprise, no surprise whatsoever. Why? The music is beautiful, memorable, poignant, but also in its own way highly visual. You know, I think that there’s a sense that he knew what he was doing. Right? If “I Guess the Lord Must be in New York City” makes sense for a movie, part of the reason is he wrote it for a movie. That’s the song he wrote for Midnight Cowboy. It’s not the one that they used, but it’s the one he wrote.

And, and I wonder if that didn’t inform some of the work afterwards whether he’s writing for films or not. That he knows what it takes. And part of it is what’s going to feel good look feel good against visuals, but also just what what’s memorable, what sticks. The genius thing about using “Gotta Get Up” Russian Doll is that if you listen to “Driving Along,” the very next song on that record, it gets deep into that kind of Buddhist wheel of life that that whole series Russian Doll is about. That whole samsara journey is actually described in the next song. “Driving along at fifty seven thousand miles an hour/Look at those people standing on the petals of a flower.” This dude was on some shit.

How do you think this podcast will change the impression on his later years?

I think some of that happened naturally to this point, and I hope we can give a little focus and a little light to how strong the songs on the later albums were. But I think it’s really just about people digging into the new record, connecting Harry’s music to the story of his life and then exploring from there. And, you know, sure, those songs are on the companion playlist to this podcast, which as they say in podcast land is available wherever you listen, but you know, I think it’s just an open doorway to discovering it’s just about opening the doorway to discovery.

Source: Read Full Article